Living Together is Easy provided a loaded and irony-laden title and thematic framework for a recent exhibition juxtaposing Australian and Japanese artists' work. Borrowed from a David Rosetzky artwork, the title was suggestive of the tensions between the commercialised rhetoric of lifestyle and togetherness that we are fed through the channels of everyday global capitalism, and the increasing alienation and xenophobia experienced by individuals living under this increasingly 'easy' (read: 'coercive') socio-cultural agenda. This tantalisingly juicy theme provides a compelling context for much current, culturally-engaged contemporary art, and co-curator Jason Smith noted a 'spirit of creative activism' as a motivator for the exhibition's rationale. A joint venture between the NGV and Tokyo's Art Tower Mito, the exhibition's theme also provided some interesting food for thought vis-à-vis the possibilities and limits of cross-cultural collaboration, setting the stage for some interesting juxtapositions between the Australian and Japanese artists' works.

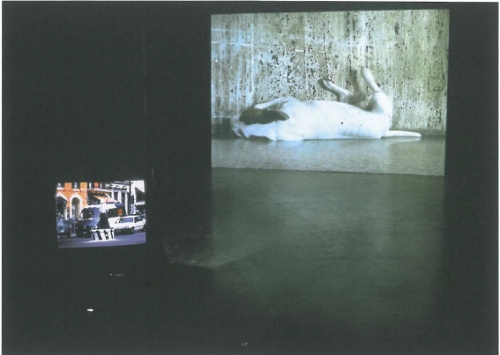

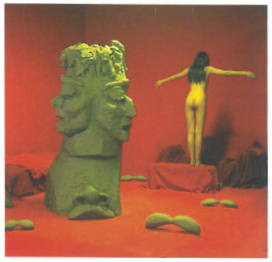

The exhibition opened with a gripping work by Japanese artist Tadasu Takamine. On a large screen mounted on a red-painted wall, directly facing the entrance to the show, a time-lapse video revealed the artist and his partner going through the motions of their everyday life: eating, sleeping, lounging, writing, making love. Dominating the centre of the frame, however, was an enormous clay head, which was progressively constructed, torn down and reconstructed through the course of the 18 days in 2002 during which the artists lived in this constructed set, a Mount Rushmore in plasticine dissolving and coalescing into exaggerated, grotesque features. Accompanied by a similarly sped-up, high-pitched voice singing God Bless America, the work spoke volumes about the increasingly invasive weight wielded by US politics on everyday global life, as well as suggesting the ways in which enacting the rituals of everyday life – doing the things that simply render us 'human' and ground us in a particular place and time – is becoming an increasingly regulated, hard-won phenomenon.

Picking up on this theme of everyday complexities, and the absurd (and often conflicting) directives of contemporary culture, were Akira Yamaguchi's mock-traditional paintings. Combining the traditional Japanese painting style of Yamato-e with absurd, eminently postmodern scenarios, and replete with killer titles like Picture of Many People Making Something and Postmodern Silly Battle, Yamaguchi's work cleverly and playfully mocked both cultural mores and dominant discourses of contemporary art.

The Australian contingent held no real surprises – at least for the NGV audience. However, the opportunity to revisit some quality works by Susan Norrie and Fiona Hall provided new food for thought, especially in light of the themes of cultural imperialism and environmentalism raised by the aforementioned installations by Japanese artists Takamine and Yamaguchi, as well as that of Kaoru Motomiya.

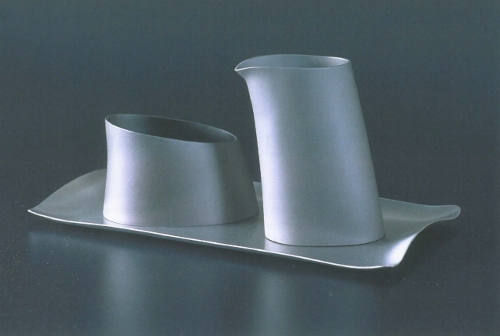

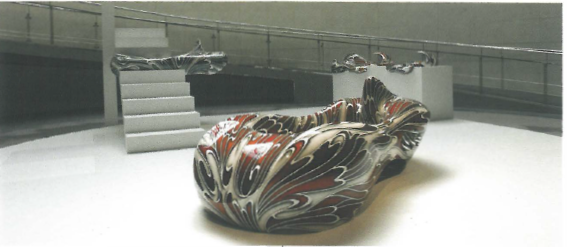

Some of the Australians' work, however, suffered for the overexposure. Ricky Swallow's Sunken Monument, for example, seems to have been so often exhibited in Melbourne in recent years that here it seemed strangely muted. Something of a misfit in the context of this exhibition, the celebrated work provided no substantial connection to the notion that Living Together is Easy, with Swallow's deliciously gothic i-man Prototypes, hybrid human skulls/i-Mac computer casings providing far more food for thought - especially when taken in relation to the anthropomorphic surfaces of Tetsuya Nakamura's supermodern appliances and fittings. These works were intriguing commentaries on the fetishes and desires inherent in 'easy' consumer culture, and picked up one thread of cross-cultural dialogue that was sadly not elaborated through the rest of the exhibition. Given the ambitious format and compelling themes, a dialogue between the works seemed too often to be lacking or absent, disappointingly missing the opportunity to really explore and elaborate the issues at hand. Despite persuasive and impassioned catalogue essays by exhibition curators Jason Smith and Eriko Osaka, the exhibition itself fell short of realising its own fascinating brief.

However, Living Together is Easy did provide an important and welcome opportunity to view the work of Australian artists alongside their Japanese peers, an unusual move for an 'exchange' exhibition, and a format which very much suited the usually exclusively Australian-oriented Ian Potter Centre. The attempt to focus on works with a political edge, albeit a subtle and understated one, was a similarly welcome move and warrants further elaboration.