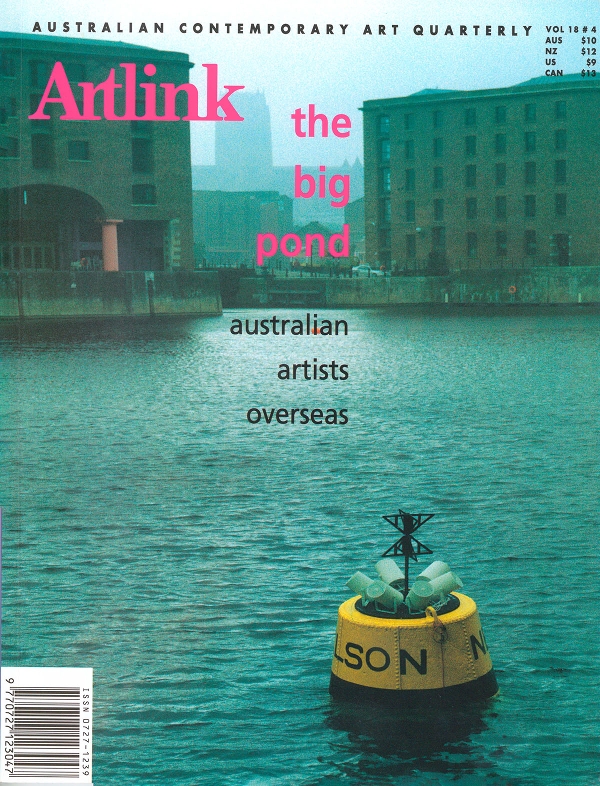

The Big Pond: Australian Artists Overseas

Issue 18:4 | December 1998

Explores the issues facing Australian artists who are working overseas or who are promoting Australian art to an international audience -- strategies, funding, exhibitions, residencies, marketing issues. Looks at contemporary and indigenous visual art practice.

In this issue

A Revolutionary Digital Summer in the UK

Digital technology is driving the revolution in visual culture and consciousness. Exploring the ninth International Symposium of the Electronic Arts [ISEA98].

Sydney Biennale Every Day

Exploration of the 11th Biennale of Sydney curated by Jonathon Watkins.

Tracey Moffatt's Lost Highway

Tracey Moffatt has since the end of 1997 had two solo exhibtions overseas -- 'Freefalling' at the Dia Center for the Arts in New York and 'Tracey Moffatt' at the Kunsthalle Vienna touring 16 galleries in Europe. She was included in the 10th Biennale of Sydney in 1996, followed in 1997 by the Venice Biennale, the Basel Art Fair and the Sao Paulo Bienal in Brazil. Adrian Martin looks at her show at the Arnolfini Gallery in Bristol.

Passion, Rich Collectors and the Export Dollar: The Selling of Aboriginal Art Overseas

The author with Djon Mundine explore the paradox which is faced by Aboriginal dealers and curators who take Aboriginal art to the world. Issues of viability to ethnocentricity and notions of the primitive as well as the role of art in educating audiences and promoting the culture of indigenous Australians are discussed.

To Go Abroad: Australians-in-residence

Explores the issues of residencies overseas for Australian artists: Jeffrey Smart, Justin O'Brien, Norma Redpath, Clement Meadmore and Colin Lanceley.

Residencies in Asia

Examines Asialink's artist in residency program. Complete with a list of Visual Arts/Crafts Residency destinations.

Seven Little Australians

Artists Louise Paramor, Yenda Carson, Damon Moon, Jayne Dyer, Matthew Calvert, David Jensz and Helga Groves write about their experiences in residencies throughout Asia: India, South Korea, Indonesia, Beijing, Malaysia, Thailand and Vietnam respectively.

The Culture of Exporting Art-cargo

How does Australia export its visual culture overseas? What have been the positive achievements and the low points of this process? Looks at the role of the Australia Council and the Visual Arts/Crafts Board.

Export What! Where!

Looks at the issues facing the export of the Australian visual art product overseas.

Narelle Jubelin at the Tate: Case No T961301

Looks at the international career and art practice of Narelle Jubelin.

Enjoin to the Philippines

Profiles the exhibition 'Enjoin' which opened in November 1998 at the Museo ng Sining (CSIS Museum) in Manila as part of the centenary celebrations of the Philippines' independence from colonial rule.

Asialink's Exhibition Program: A Sampling

Describes Asialink's exhibition program which commenced in 1991 at the same time as the residency program with funding from the VACB and the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade.

Telling Tales to Austria

Telling Tales an exhibition curated by Jill Bennett and Jackie Dunn about trauma, subjectivity and memory began an international tour in March 1999 as part of the SOCOG Cultural Olympiad 'Reaching the World' . Opened at the Ivan Dougherty Gallery at the College of Fine Arts Sydney in conjunction with a major conference 'Trauma and Memory--Cross Cultural Perspectives'.

Larrikins in London to London

An exhibtion curated by Nick Waterlow and Felicity Fenner which examines the extensive and multifarious nature of the cultural exchange which took place between London and Australia in the 1960s. OZ magazine and activists and writers such as Germaine Greer, Juno Gemes, Robert Hughes, Clive James, Richard Neville, Robert Whitaker and Wendy Whiteley provide a vehicle of narration for the exhibition. Part of the Olympiad theme of 'Australia to the World' 1999/2000

Parachuting Postponed: Birmingham

Claire Doherty is a curator at the Ikon Gallery in Birmingham, England's second city. The 'Art into Action' program supports artists working in process based or research based ways over extended periods of time in direct communication with groups and individuals in Birmingham. The exploration of 'home' suggested itself as a universal metaphor as the 'sacred place' from which all else could be mapped.

International Programs

Discusses the cultural policy of the Victorian Government Arts 21 promulgated in 1994 which aimed to reinforce the government's agenda to promote Melbourne and Victoria as an international centre of excellence.

Kultural Kommuting

Kultural Kommuting is a collaboration between 18 artists resulting in installations in public locations in Melbourne and Berlin during 1998. Initiated by Claudia Luenig and Maggie McCormick, Kultural Kommuting is a 'cityartpublicspace' project run in association with Galerie Trepenhaus and the Public Office and is a project of the City of Melbourne's public art program.

John Kelly: London to Brighton

John Kelly was the recipient of a Samstag Scholarship in 1996 to study at the Slade for a year. The article looks at Kelly's current work and the tensions between working in London and Australia.

Steven Holland: Game Over

Steven Holland was awarded a Samstag scholarship in 1997 which allowed him to enrol in Natural History Illustration and Sculpture at the Royal College of Art in London and to travel to Europe.

Zhong Chen: Adelaide - London - Adelaide

Zhong Chen as a relatively recent graduate of the SA School of Art won a Samstag Scholarship to travel to the Chelsea College of Art in late 1997.

Nike Savvas: Joining the Inner Circle

Nike Savvas was awarded a Samstag Scholarship in 1996 ans was accepted into Goldsmiths College as an Associate Research Student. She has instigated a number of one day exhibitions with artists from Australia and Europe along with fellow students from Goldsmiths.

Simon Mangos in Berlin

Explores the work of Simone Mangos who left Australia in 1988 to spend a year as an artist in residence at the Kunstlerhaus Bethanien in Berlin. During the past 10 years she has maintained a profile in Sydney and Adelaide. Mangos creates site specific installations as well as discrete objects that can be exhibited in art galleries and art fairs.

An Australian or Two in Paris Nineties-style

On four Australian artists working in Paris: Marion Borgelt, Tim Maguire, Helen Kennedy and Heidi Woods

Annette Bezor in Paris

Since 1986 Annette Bezor has been working in both the Cite Internationale des Arts and private studios in Paris. The Adelaide Paris connection, seemingly so contemporary is very much a part of South Australian visual art history. Conducted as an interview with the artist.

Jill Scott: Zurich, Weimar and Sydney

Jill Scott writes about her experiences in Europe particularly Germany. Short biographical details of the artist are also included.

Aldo Iacobelli in Valencia

Explores the artistic tension in the work of Aldo Iacobelli --- between Australia where the lack of tradition may be seen to allow greater movement of ideas and Europe where the cultural territory is much more established.

Anne Pincus in Munich

'Ask the dust' the exhibition of Anne Pincus at Access Gallery in Sydney explores the contrast between the light and sand and dust of Australia and Israel and the darkness of Europe.

Dorothy Erickson: Jetset Jeweller

The strength of the Australian jewellery practice may be attributed to the jewellery departments in Australian universities and art schools as well as to the influence and impact of leading jewellery artists who have arrived from other countries to live, teach or practice in Australia. Looks at the work of Dorothy Erikson.

Get Out There and $ell

Explores the international art market for serious contemporary art, looking at the Australian Visual Art Export Strategy.

Who's Selling What to Whom: Australian Dealers Taking Australian Art Overseas

Although the US is often cited as the holy grail for export, with its huge art-aware public and wealthy collectors, and although it is true to say that many Australian art dealers have links with US dealers and sales are made on a fairly regular basis, Japan, Germany and Spain are the countries to which Australian commercial galleries have exported Australian art since the early nineties.

ODD: business, news, finance and weather

Andrew Petrusevics and Chris Gaston

Artspace, Adelaide Festival Centre

28 August to 24 October 1998

Entree: Emerging Adelaide Artists

Curated by Di Barrett

Nexus Gallery, Adelaide

September - October

Expanse: Aboriginalities, Spatialities and the Politics of Ecstasy

University of SA Art Museum

4 September - 3 October 1998

Curated by Ian North

Warka Irititja Munu Kuwari Kutu/Work from the Past and the Present

A celebration of fifty years of Ernabella Arts Tandanya National Aboriginal Cultural Institute, Adelaide

August - September 1998

Sit Up! and Nature as Object

Sit Up!: 100 Masterpieces from the Vitra Design Museum Collection

Nature as Object: Craft and Design from Japan, Finland and Australia

Art Gallery of Western Australia

2 July - 6 September 1998

Past Tense/Future Perfect

Craftwest Gallery, Perth and Moores Building, Fremantle

4 - 26 July 1998

Centre for Contemporary Craft, Customs House, Sydney

12 September - 11 October 1998

Divergent: Abstraction and the Photographic Object

Recent Works by Adam Bunny, Jane Burton, Penelope Davis, Gavin Hipkins, Brian Jefferies, David Martin, Jeffrey Sturges & Andrew Wilson

Curated by Simon Cuthbert

Plimsoll Gallery, Centre for the Arts, Hobart, September 11 - October 4

The Meeting of the Waters: The Australian Print Project

24 Hr Art, Darwin

September 1998

The Wild(e) Colonial Boy

Leigh Bowery

edited Robert Violette

published Editions Violette/distributed by Thames and Hudson

$89.00 238 pp colour and b&w illustrations

White Aborigines: Identity Politics in Australian Art

Ian McLeanWhite Aborigines:Identity Politics in Australian Art. Oakleigh, Vic, Cambridge University Press, 1998, 204 pp. RRP $39.95 hb.

Artrave