‘Disability +’ is a relative blind-spot in the multifarious art worlds that we inhabit, and its language and expression is complicated by fear and ignorance in some quarters, and strong and opposing views in all quarters. It may have taken a pandemic to rattle the cage of the abled—but whether it has prompted a revolution or a minor ripple across the art worlds’ pools of power remains to be seen. SENSORIA: Access & Agency is Artlink’s effort to affect this swell by providing a platform for divergent perspectives and nuanced articulations of being an artist. Whatever the prevailing conditions. It also invites a discussion within contemporary art discourse that is not driven by fear (of getting it wrong, of ‘the other’, of adding injury to trauma). Art is our place of intersectionality: if you’re reading Artlink, you’re already on the margins, and quite possibly on the spectrum.

Most of the writers and almost all the artists profiled or discussed in SENSORIA live with disability, impairment or neurodivergence. As became crystal clear in meetings and conversations with the writers over the course of this issue, there is no single correct term for disability—or more accurately, no consensus. (No surprises there.) Like most areas of contemporary life, any ‘terms’ we seek need to address a whole of society’s pluralist make up. Some of our writers claim ‘disabled artist’ or ‘artist with disability’ as identifying terms. Others are more specific: vision impaired, d/Deaf, autistic, neuroqueer. Or they remain private about their personal physiological histories and diagnostic status. Some writers are explicit in their ideologies and identity politics; others are more circumspect. At the risk of generalising, most subscribe to the social model of disability; that is, a view that the sociocultural—or economic, political and institutional structures that we live within (often typified in arts journalism as neoliberal, ableist, capitalist), are the disabling features of their/our worlds. By contrast, the less-progressive medical model of disability problematises the person/body, and is driven by treatments, ‘fixes’, and curative measures. There are also semantic and historical differences between Australia, NZ the UK and USA, and in the conceptualisation of disability/divergence in Indigenous world views.[1]

This is very much a shifting glossary, and these seem blunt instruments of language, policy drivers rather than philosophy, being used to describe complex histories and individual experiences. A jungle of theories has been propagated to make sense of, and to complicate, lived experience and creative work across a vast range of positions, much of it developed by artists as insiders to the experience of disability/divergence, plenty of it finding a home in art writing and practice. As introductory visual analysis teaches us, the combined sensorial experience of art—immersed in an aesthetics of image, sound, structure and scent, (potentially anaesthetised or electrified by its power)—there’s no single theory that fits the work of art, or the ‘bodymind’, without tight corners or sloppy edges. Art’s perceived aura often can’t be explained, accounted for, comprehended. Reception theories remind us that the ‘beholder’ has more than ‘an eye’—they/we are vessels of history and biography/biology/sensoria/stories. But several writers in this issue do tackle these taxonomic challenges, unpicking the knots and—often playfully—working their linguistic tools to lead the reader to failures, idealism, hope and beauty across the uneven art world and the labour and work (of art) that underpins it all.

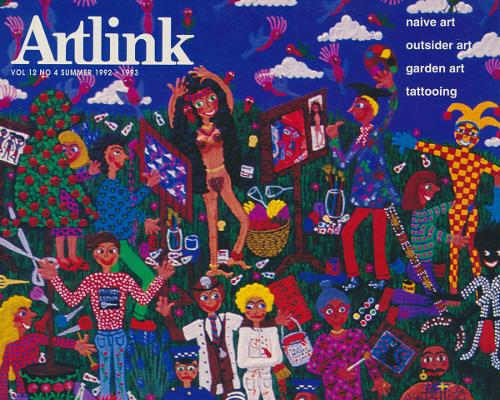

There’s the old logic that ‘to learn from history, you have to do history.’ Artlink’s back-library has been front of mind since our COVID-inflected mid-life crisis of 2020-2021. Starting in 1981 (incidentally, the United Nations International Year of Disabled Persons), Artlink’s archive hides both skeletons and gems. In the summer of 1992–93 we published the Naïve & Outsider Art issue, now out of stock; thirty years on, a summary glance of the magazine reveals an unlikely assemblage of types and tropes. As Juliette Peers observes in her online Archive Project essay “Inside the Outsider issue”, disability/neurodiversity and medicalised ‘care narratives’—as well as the self-taught, mentally ill, vanguard and eccentric practices—have not followed as clear a trajectory as, for example, Indigenous and feminist art practices over corresponding years.

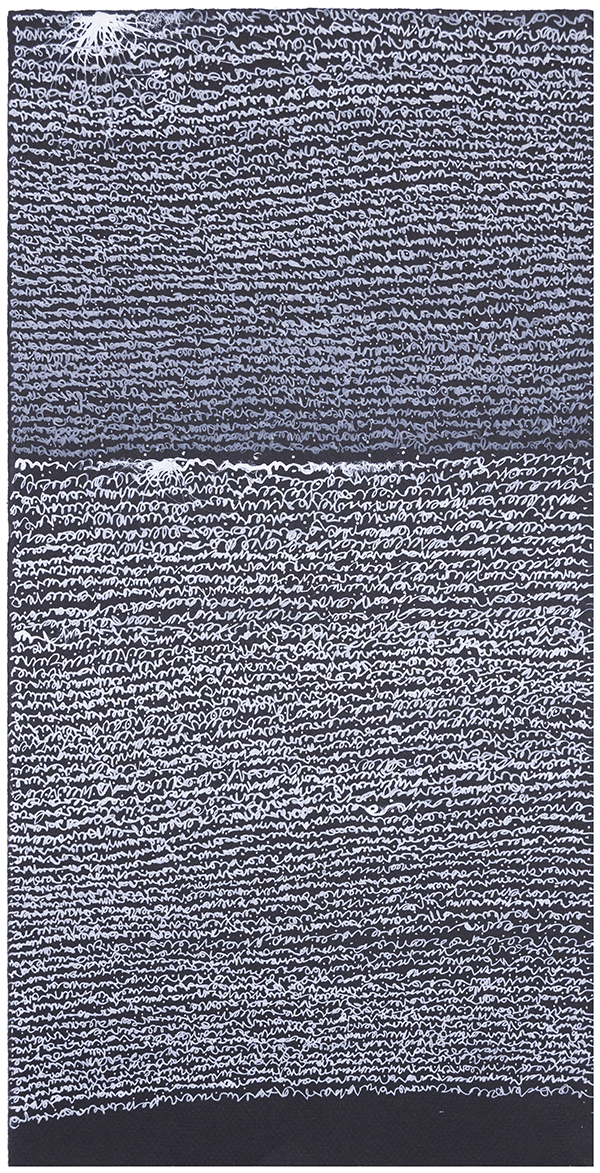

In SENSORIA, the narrative of divergence is more composed and more designed, but we nearly printed our cover image, Ruark Lewis’ SPEEDY PAINTING New Year (2022) upside down, which would have brought a new twist to the outsider position. A sound transcription from the poem New Year written and spoken by the late Ania Walwicz, it is emblematic of Lewis’ recent durational paintings, ‘sonic, literary and time-based...’ as Marielle Soni writes in her enigmatic profile on Lewis, “Thinking without fear”. For the obsessively inclined reader, the visual arc across lead images linking the essays—each layout tenderly tended to by Kimberley Baker of Flux—is a para-aesthetic pleasure, and I prescribe a cover-to-cover immersion for full effect.

Access has been paramount to the discourse of art and disability. In our title and resonating throughout many of the essays, it takes on multiple intentions: as a metaphor for entrance, for inclusion, for representation and for conceptual access—to ideas, to art, to a ‘sensus communis’, a body politic. Access in its various manifestations is a challenge for us all in different contexts, forever waiting to make itself felt. Or to fail us. In this line of enquiry, Tara Heffernan applies an audit to recent exhibitions in Melbourne and Brisbane which have addressed accessibility in public and online spaces, and Bruce E. Phillips makes a forensic (and fairly futile) search for ‘neurodiversity+’ as a key term in Aotearoa/New Zealand exhibition histories—but his research trail of crumbs offers rich pickings. Of a much more serious nature, Tarntanya/Adelaide based collaborating artists Kurt Bosecke (of Tutti Arts) and Emmaline Zanelli (aka the A.B.C.D.E.F.G.H. Project Researcher Team) deliver their findings on the nutritional index value of the Art Gallery of South Australia’s Collection.

Agency is about human rights, equity, respect: having agency to work autonomously, collaboratively, assisted or collectively is paramount for all artists. The work of five artist collectives are represented in SENSORIA, each with a unique history grounded in community arts models and most now registered NDIS service providers. Arts Project Australia in Northcote and Collingwood (est.1974) is the country’s longest running supported studio, and Sim Luttin describes their current advocacy work and international partnerships with Art et al. Twenty-two years ago in Hornsby, Studio ARTES grew from the efforts of a group of volunteers working out of a garage, and today under the Studio A banner in Crows Nest, many of the artists are achieving wide public recognition and lucrative art commissions. Treating their Artlink spread as an illustrated Q&A, the ‘A-team’ share their job descriptions and creative inspirations.

Located beyond the machinations of metropolitan art worlds, Joy Naden writes affectionately on three Tiwi artists she has worked closely with for 28 years in Wurrumiyanga, Bathurst Island: Lorna Kantilla, Alfonso Puautjimi and Jane Tipuamantumirri. A small not-for-profit art centre, Ngarruwanajirri is unusual in having such long-term management in place, and in this instance the stability has facilitated painting careers which span decades.

Working on the Noongar nation of the Whadjuk and Yued, and the Southern Yamatji Peoples in Western Australia, DADAA supports creative artists across all forms and via regional and international outreach programs. DADAA’s lock-down experience has generated a work with Graeae Theatre in London, which is being translated into a theatrical production for Australian audiences in 2023. Graeae’s artistic director Jenny Sealey’s personal story of leadership in the arts as a Deaf woman who experiences a double imposter syndrome is applicable to numerous cultural industry settings. She describes the fury she feels after a quarter-century in the game when promoters ask, ‘Jenny, it is best if we don’t mention disability or access in our publicity as it will put people off. Don’t you agree?’ There is darkness at the heart of this WA/UK collaboration, which leans to the therapeutic in its value, but this too is a contested space. As M. Sunflower, an artist and advocate for young artists with disability told me, ‘to use the terms [art and therapy] implies all kinds of training…so I avoid that.’ She writes from the heart of her experiences of anxiety-and-pandemic induced lockdowns and as a university student in a system sympathetic to ‘equity, access and diversity’ but ultimately indifferent to individual struggles. For M. Sunflower, relational, accessible art workshops have been transformative.

Virtual relations have become mainstream since 2020, but for neuroqueer-kin Alison Bennett, a maestro of expanded photography, and dancer and choreographer Dean Walsh, the rehearsal—their long engagement—has run for a decade. Their online exchanges about autism and water immersion as an ecological, therapeutic and creative method has been compressed here, but they cite key concepts in relation to neurodivergent intersectionality, queerness and posthumanism. Working to more concrete principles of time and space, Jane Trengove and Olga Bennett have spoken and written together and with exhibiting artists, reflecting on “Other Body Knowledge” in a move away from ocularcentrism. They too rap lightly with the discourse of art and disability: as Fayen d’Evie suggests, it’s about ‘diverse perceptual entry points into […] creative conversations.’ Within the same context, Sam Petersen’s sardonic and equally tender poem on care coupled with ‘disabled wee’ reprises punk and avant-garde performance art—a radicalism that art institutions seem tickled by…but they are kind of missing the point.

If the facemask has become a material symbol of care (and respect to others and self), one we all had dependency on during the height of public health restrictions, words are more slippery tokens: names even more so. Our discussions around issue 42:2 began during 2021 lockdowns, but we were not in lockstep with a title until late in the piece. The original working title generated robust debate in the drop-in writer’s zoom-rooms which have been a kind of therapy for me—if no one else. But this is no treatise on ‘ableist awakening,’ despite the generous and instructive texts within. Our final online meeting to hammer out a title was well-attended, and there is another essay of interpretations and grammar around the term disability saved in the chat. We decided against a prosaic ‘housekeeping’ model of description—not to eschew disability+, but to amplify ‘what we want to move towards.’ After all, words are our muse. As another writer commented, ‘for fear of wandering far from the sacred, it’s sexy.’ SENSORIA: Access & Agency was brought to you by the band. Everyone was on drums.

Footnotes

- ^ See Kate Larsen, Larsen|Keys for an abridged history of disability models, best practice in art writing on disability and a collection of resources on disability-led language: https://larsenkeys.com.au/2019/09/21/resource-disability-models-and-language/