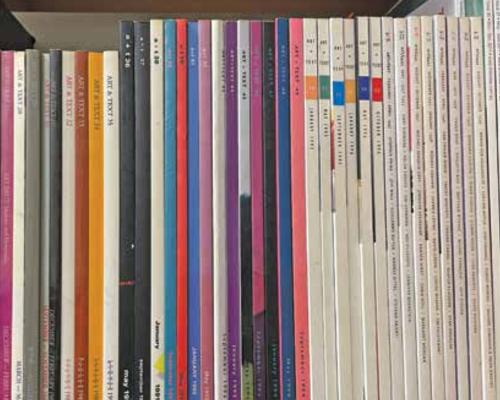

The Artlink Archive Project: Jacqueline Millner and the art writer’s marathon

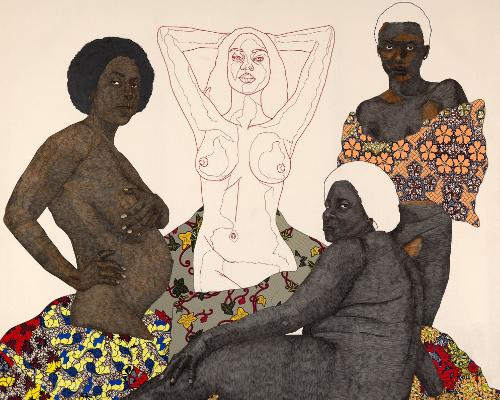

As an arts writer who began their career in the mid-90s, in the wake of the high-water mark of critical theory in art schools’ art history departments, I’ve always been conscious of the links between philosophical developments (and fashions), and art writing in its various guises. I have also been aware of the swing from privileging the text to the centering of the object in all its materiality, and the parallel blurring of the lines between artist and writer alongside the rise of the artist-researcher. These broader moves and the role of, and effect on, art writing are of particular interest because of their implications for the feminist project, a central concern in my practice as a writer and educator. It was, after all, feminist readings and applications of Michel Foucault and psychoanalysis that first spurred my thinking as an arts writer. These complex relationships between power, ideology, images and bodies brought an understanding and a meta-language to my lived experience. This essay tracks developments in feminist art writing by reference to key issues in the Artlink archive: “Art and the Feminist Project” (1994) and “Positioning Feminism” (2017), with some reference to “Men’s Business: Masculinities Reflected” (1996) and “Sexing the Agenda” (2013). Artlink has been a major site for the publishing of feminist discourse, promoting writers and artists both in and outside of dedicated issues. Inflected through the lived experience of writing about (often) women’s art, this article offers a historiographical backward glance to help understand the present state of feminist art writing, and Artlink’s history in this field.