The indisputable historical link between modern art and urbanisation sometimes overshadows innovative forms of contemporary cultural production that emerge in response to economic, demographic and social changes in rural areas. Luckily, not everyone is oblivious to these innovations, and there are important initiatives that chart and interpret them. One recent example is Countryside, The Future, an ambitious exhibition created by renowned architect Rem Koolhaas that opened in February 2019 at New York’s Guggenheim Museum. Equally significant was Milan’s 2019 international triennial of design. Titled Broken Nature and curated by Paola Antonelli, the event highlighted contemporary design’s potential to repair environmental damage and heal the rift between industrialisation, agriculture and nature. Also noteworthy are The Rural, an MIT Press anthology of writings on the relationship between modern art and the rural, and Taking Place, a symposium on similar issues held at the Bundanon Trust, both occurring in 2019.

The complexities surrounding the relationship between contemporary art and non-metropolitan communities were in evidence at the latest iteration of Cementa, a biennial art festival held in Kandos, a small town in the Central Tablelands of New South Wales. The event is significant because, among other things, its founders and many of the participating artists are established professionals who left Sydney to relocate to small country towns around the Blue Mountains and beyond. Writer, academic and curator/producer Ann Finegan was one of the first to move to Kandos, and her presence in town became a catalyst for creative energies that led to the development of Cementa, an event she co-founded with artists and former Sydneysiders Alex Wisser and Georgie Pollard. While Finegan withdrew from the festival in 2017, handing over her curatorial role to Wisser and Bec Dean, she continues to develop work at Kandos Projects as an independent producer.

If you thought that two ongoing contemporary art initiatives in a town of 1,200 inhabitants was enough, think again. There is also the Kandos School of Cultural Adaptation, a project at the crossroads of art, agriculture and environmentalism that evolved from a work Ian Milliss created for Cementa 2013, and Wirimbili-Yanhi Wiradjuri Walan, a new Aboriginal cultural centre inaugurated during last year’s festival, with an exhibition curated by Djon Mundine. This remarkable “art ecology”, to borrow one of Australia Council’s favourite truisms, is one of the byproducts of an intellectual diaspora caused by Sydney’s spiralling real-estate prices. There was a time when artists congregated in run-down inner-city areas; now some of them prefer small country towns affected by economic and demographic decline, a trend that has the potential to transform the socio-economic conditions under which contemporary art is produced and distributed.

The 2019 exhibition was the first Cementa I’ve attended, so I’m unable to compare it with previous iterations, but I found many of the non-time-based works included in this exhibition to be somewhat perfunctory. I suspect that, at least in some cases, they were little more than tickets of admission to an event whose essence is fundamentally social and celebratory. Even artists renowned for their ability to over-deliver, such as Claire Healy and Sean Cordeiro, kept things small scale. But none were smaller than Keg de Souza’s Cement Blocks, a box of icy poles, which the artist had confected from ingredients that made them resemble small blocks of frozen cement (and they were delicious). Like other works in this iteration of Cementa, it was a witty but fundamentally unambitious conceit, an assessment that can be extended to the handful of small collages created by Deborah Kelly and the women who participated in her workshop, amusingly named Women with Knives.

But it is hard to blame the artists, many of whom are very talented, as they were given tiny production budgets and (in most cases) had only one week or so to explore the town and create the works, a problem that also showed up in technical shortcomings, as when audio-video equipment proved unequal to the sometimes-difficult environments. Size may not matter in art, but time, budgets and appropriate equipment do, and even the most dedicated artists cannot always compensate for a lack of adequate logistics support. Another drawback was that most non-performative works were ensconced in indoor venues, such as the town hall (bare as one of Pieter Saenredam’s whitewashed church interiors) and the local museum (a temple of relentless hoarding and curatorial kenophobia, and well worth a visit).

It is telling that the most visually and technically accomplished artistic object I saw in Kandos was not by a visiting professional artist but produced by Annaleigh Moore, a local high-school student. Several years ago, she created a dress and accessories made of cement bags from the local, now closed, cement factory, once central to the economic life of the town. The work, which is preserved in the museum, reminds one of the Russian Constructivist designs produced during the post-revolutionary period, a remarkably accomplished achievement for such a young creator. Moore’s dress and the history of the cement manufacturing plant were also the theme of a dance performance that Susan Barling presented on the third day of the event.

Some of the time-based work succeeded in transcending these limitations. My very first Cementa experience was an encounter with a shirtless shaman, his head encased in what looked like an oversized fencing mask covered in fabric. He was roller-skating around an empty basketball court, occasionally striking a large bronze bell with a hammer. It was Kozie Rogi, a performance by Sydney artist Szymon Dorabialski, which reminded me of the ritualistic athleticism of Matthew Barney’s early work and, perhaps also, the “cosmic” theatricality of Sun Ra. The eeriness of Kozie Rogi well-suited the stillness of that corner of town at that time of the morning, with the sky above laced with a smoky haze created by the surrounding summer fires.

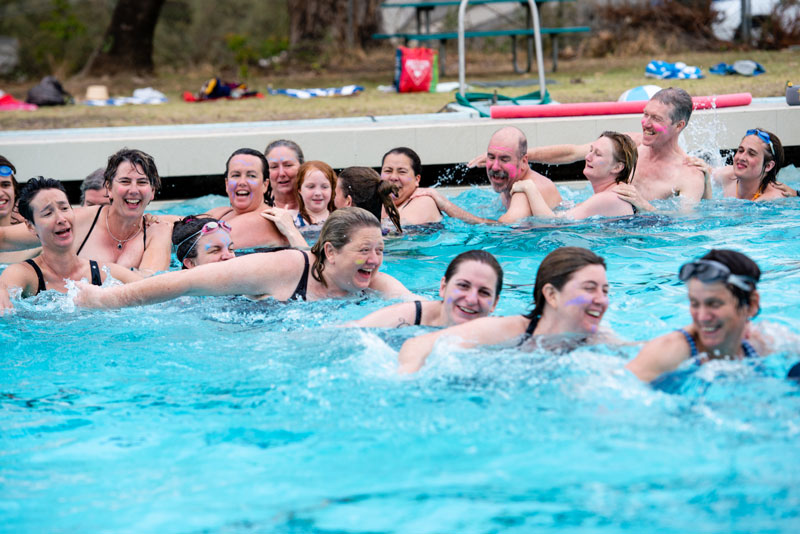

PYT Fairfield’s performance at the municipal swimming pool was also memorable, not only for its narrative content, which dealt with childhood memories of swimming pool experiences, but also as a demonstration of the artists’ ability to engage their audience. The “participatory” strategy was brutally simple: they got the spectators into the water and sternly ordered them around. It was oddly satisfying to see a bunch baby boomers and generation Xs, many with PhDs, rediscovering with excitement bodily delights they hadn’t enjoyed since puberty, all the while being reprimanded by their “instructors”. Equally successful was Circumnavigate Kandos in Our Clothes, a community performance conceived by Alba Stephen, featuring a set of outlandish gender-bending outfits designed by Rachel Buckeridge. The conceit was to let anyone who was so inclined borrow the clothes and wear them around town, thus making participants peripatetic agents of visual detournement (but this work, it must be noted, was not part of Cementa’s official program; rather, it was organised as a “Fringe” event by Kandos Projects).

In some respects the most thought-provoking event I attended was the performance night at the RSC Club. This was quite an occasion because the hall was jam-packed with both artists and local residents, the two worlds literally rubbing shoulders and feeding the intense energy of the room, an excitement that even the uneventful raffle could not diminish (the prized tray of meats was left unclaimed that night). As the show started, most performers read the room correctly and stuck to good-natured cabaret goofiness, except for Giselle Stanborough, whose contribution to the evening was a lecture-performance on the ideological underpinning of popular culture’s representations of the bush. Unfortunately, the artist’s PoMo irony got lost in that rowdy environment; I was standing next to the bar and my neighbours’ impatience was palpable.

This should not be taken as a sign of broader fracture between artists and locals, for a degree of occasional bad temperedness is inevitable when the avant-garde and the person-in-the-street meet in a bar. To gauge the health of such a complex relationship one would need much more than the random anecdotal observations of a visiting art scribe. This reminds us that the challenges facing contemporary artists working small rural communities are considerable, not least because they must relinquish the protection granted by their customary inner-city havens. Small towns don’t offer the luxury of self-segregation; artists must interact with their neighbours and negotiate these sometimes-profound ideological divides without losing themselves in the process. This is a difficult balance to strike, especially considering that conflict can be destructive in small towns where everyone shares the same, limited social space.

Contemporary art propension for “criticality” sits awkwardly in a context in which if you start burning bridges you will soon find yourself with nowhere to go. These social conditions sometimes induce artists to play it safe by indulging in populist aesthetics, as evidenced by the new fad of defacing the stark beauty of old silos with quasi Social Realist murals. Cementa should be credited for not falling into this trap while offering opportunities to local and regional artists, who were included in a couple of curated exhibitions. It was an appropriate openness that mitigated the risk that the event may be perceived as a get-together for city artists looking for a bucolic sojourn.

But how does one critically evaluate Cementa? Should one focus on the product or the process, the concrete artistic results or the often-intangible process of social engagement? Undoubtedly, projects that straddle the boundaries between art, agriculture and environmentalism are essential in an art world dominated by commercial art fairs, off-the-shelf biennales and corporatised art institutions, if nothing else for the spirit of generosity and selflessness that motivates those who contribute to them. The problem is that the visible artistic outcome of socially engaged art is the proverbial tip of the iceberg; underneath lies a depth of social interactions and relationships that are out of sight.

Grant Kester, one of the main theorists of these types of practice, has argued that intersubjective relationships between artists and community participants constitute a new form of “dialogical aesthetics”, the value and meaning of which is independent of any tangible artwork that may, or may not, be produced. This position gives due credit to the importance of the human interactions, but also creates interpretive difficulties. Taken in its purest form, dialogical aesthetics does away with not only audiences – in that aesthetic experience is reduced to a personal relationship between participants – but also the artwork itself. Often, after these dialogical projects are over, there is nothing left; or. at least nothing that can be shared, transmitted, reinterpreted and misinterpreted – nothing that can become a monument or at least a document.

This kind of radical ephemerality is different from that of other forms of performance or time-based work. The latter have audiences that anyone could, in principle, be part of; hence, they can aspire to general or even universal significance. Conversely, the practices championed by Kester are localised and personal, not unlike relationships between lovers, friends or family members. The problem is that unless a love story or a friendship is turned into a book, or a film, or theatre piece, or any other sharable work, it remains a private affair. It may seem anachronistic to invoke universality at a time when radical pluralism and the endless proliferation of particularised identities – based on gender, sexuality ethnicity, religion etc. – reigns supreme. But how can one build bridges between this archipelago of separate identities if not by presupposing a yet-to-be-achieved universality? The over-emphasis of “process” over “product” diminishes the role of artworks as tokens of exchange between different subjectivities and identities. Of course, the universality promised by the artwork is a never-to-be-achieved-limit case, but it is only one the ways in which we identify the principles that guide us as we strive to clear a new shared ground for the coming community.