The Tagalog word bayanihan describes the practice of communally lifting and transporting a house from one location to another. The symbolic potency of community members coming together to achieve what an individual cannot has also led to an expanded use of the term to represent broader notions of civic unity and collectivism. Anticipating that a program framed by notions of civic unity would inevitably seek to promote a unified cultural identity, I approached the Bayanihan Philippine Art Project (a multi-arts program involving five cultural institutions across Sydney) with a degree of trepidation. Thankfully, the four exhibitions I visited avoided adhering to a uniform vision of Philippine contemporary art, in favour of presenting a diverse range of perspectives and modes of expression. In this, I was reminded that the Philippines is a country accustomed to negotiating a multitude of cultural influences and competing perspectives, and that collectivist approaches need not require uniformity.

Passion and Procession at the Art Gallery of New South Wales presents the work of ten contemporary artists from the Philippines curated by Matt Cox. The exhibition begins with a procession of sorts, like the ceremonial intent of the Catholic Stations of the Cross. Its entrance requires visitors to tread a line along the exterior wall and double back into a constructed corridor before reaching the main space. Installed along this path are works that span a period of more than two decades, from 1994 to 2017, and introduce a visual language packed with iconography, appropriated imagery, cultural and historical cross-references, and visual and textual puns. It is a vernacular capable of articulating the multiplicity of cultures and belief systems that have clashed and synthesised throughout recent Philippine history, and continue to shape the current context.

.jpg)

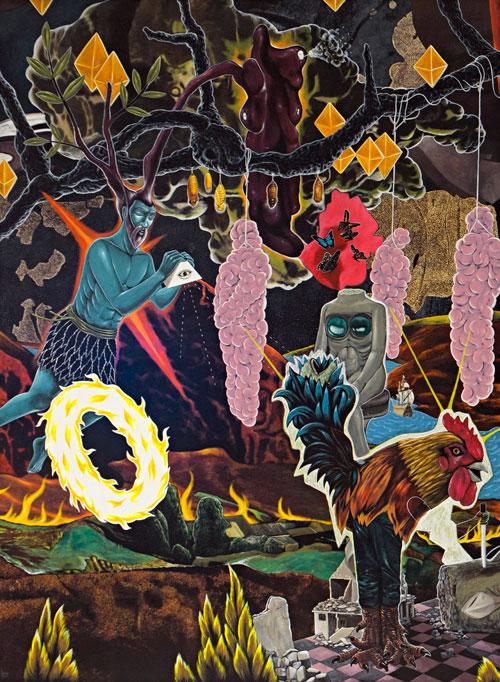

Adda manok mo, Pedro? (Do You Have a Rooster, Pedro?), Rodel Tapaya’s seven-metre wide painting, is the first work to greet the audience. Chicken-headed soldiers engage a masked army in a battle for territory, around which a cast of colourful characters jostle for space. With references to indigenous folklore of Northern Philippines, the Christian story of Saint Peter and a fatal clash in Muslim Mindanao, Tapaya traverses the country from north to south, integrating age-old stories with contemporary events. In reconfiguring indigenous folklore to investigate the current context, Tapaya explores the continued relevance of pre-colonial cultural practices while simultaneously challenging static representations of culture.

After the visual spectacle of Tapaya’s immense painting, it would be easy to skim past the small works on board and paper by Santiago Bose, but in fact they hold within them worlds just as layered and complex. In his series Faith and science in the time of AIDS, apologies to Dr José Rizal (1996–97), Bose appropriates cartoons made by Philippine national hero José Rizal in 1892 to illustrate the interplay of poverty, religion and superstition in determining the society’s response to the AIDS crisis. In referencing Rizal, Bose juxtaposes the nationalist concerns of the late nineteenth century with persistent structures of inequality, highlighting the destructive legacy of Spanish colonisation in the century that divides the work of the two artists.

Entering the main space, Catholic processional staffs incorporating folk and indigenous symbols wind their way across the floor in Renato Habulan’s Pilgrimage (Lakbay panata). Nona Garcia’s Recovery (2017) extends Habulan’s consideration of syncretic belief systems by exploring the relationship between traditional healing practices and mainstream medicine. Her wall-bound installation presents 60 x-ray images of objects significant to indigenous groups in the Cordillera region of Northern Philippines. On the opposite wall, in Geraldine Javier’s The Bond is Stronger in the Age of Division (2017), the exposed root systems of delicately embroidered plants reach beyond their individual frames and intertwine in a tangle of silk thread. It is a quietly powerful work that speaks of connections and entanglements that exist beneath and beyond the external markers of identity that unite and divide us.

While Passion and Procession focusses on perspectives from within the Philippines, the artists exhibiting in Haló at Mosman Gallery occupy an in-between position that sees them move in and out of the cultural contexts their work investigates. The exhibition presents a number of major projects by artist-pair Isabel and Alfredo Aquilizan, who currently move between Brisbane and Los Baños, and two video works by Sydney-based artist JD Reforma.

Framed: Mabini Art Project occupies the ground floor gallery and is the latest iteration of a project first presented by the Aquilizans in 2011. It centres on the reconfiguration and re-contextualisation of “Mabini Art”, a style of painting that typically depicts romanticised images of the Philippines, popularised by the tourist-driven market of the 1950s. Collaborating with Mabini artist Antonio Calma, the Aquilizans slice up an idyllic island landscape and hang their selections salon-style in a space that is usually home to Australian Impressionist paintings of Sydney Harbour, thus pulling off a double critique of the constructed ideals of both the Philippines and Australia.

The artist-pair continue their appropriation of popular culture to critique the western gaze in Island in the Pacific: Project Another Country (2017). Postcards depicting idyllic tourist destinations of the Philippines, each one held by a Filipina figurine, climb the wall of the staircase and lead into the works of JD Reforma. Incoming helicopters and a mad dash through the jungle cuts to linen suits and cocktails in Reforma’s Coconut Republic (2017), a video work that combines scenes from five American-made films shot on Philippine soil but set in other countries. In removing these images from their original context and presenting them anew, Reforma does to the films what the films did to the Philippine landscape. It is a second act of appropriation that works to reveal the first.

Further to this, Reforma uses the films’ own language of war and invasion to explore broader questions of US cultural imperialism. Coconut Republic (2017) is a clever work that extends the exhibition’s exploration of the role of representation in constructing place. Reforma’s second video work, Confidently Beautiful, With a Heart (2017), centres on Pia Alonzo Wurtzbach, Filipina and Miss Universe 2015. A mash-up of footage shows Wurtzbach receiving the coveted crown, discussing US military presence in the Philippines, conducting a make-up tutorial, and taking selfies with President Duterte. The work’s conflation of US cultural imperialism with the current political context seemed to lack analysis and consequently felt like easy pickings when looking for something to say about the Philippines. Coconut Republic is a much stronger work by comparison, both independently and in the context of the exhibition.

Cardboard shanty towns assembled to form giant ships take over the upper floors in Head | Land: Project Another Country (2017). This is another ongoing collaborative project of the Aquilizans, which involves working with community members to make the individual cardboard shelters before assembling them on site. The project contains the artists’ signature themes of transit, migration, and belonging. More specifically, it responds to their work with the Badjao people who, prohibited from practising their nomadic, seafaring lifestyle, live in makeshift settlements dotted throughout Southern Philippines.

In the second part of this work, Badjao children rap and play home-made instruments across a five-screen video installation. They appear joyfully defiant, in contrast to the world weariness of the older community members interviewed. As they rap in Cebuano and Tagalog, the two most widely spoken native languages in the Philippines, I wondered if there is a third language I cannot detect – one that is really their own. This is a powerful reminder that structures of cultural dominance exist within countries as well as between them, a fact often flattened by the global cultural order of “the West and the rest”.

I left Haló’s explorations of the Western gaze to see the works of an Australian artist who has built his practice on observations of the Philippines. I wasn’t expecting to be overwhelmed by David Griggs’ survey exhibition, Between Nature and Sin, at Campbelltown Arts Centre. Having seen recent works in Adelaide and Manila, I had come to the conclusion that he fell in somewhere behind the best of the Manila-based artists painting in that scrappy and irreverent style, smashing colour and pop culture onto the canvas to convey the mad mix of the city and beyond. I was therefore surprised to find a powerful and challenging exhibition, broad in reach and full of substance. I walked away from it feeling that certainly I had underestimated him.

The exhibition takes off from 2005, the year of Griggs’ first trip to the Philippines, presenting work produced over a twelve-year period and including paintings, photographs, videos and his feature film, Cowboy Country (2014). To enter the exhibition is to be hit with what is bemusedly referred to in the Philippines as the “maximalist aesthetic” of Manila. Like the metropolis Griggs now resides in, everything is big, clashing, colourful and overlapping: from the works to the carpets to the walls, more is more is more.

Painted canvasses clash with camouflage-painted walls in Griggs’ 2005 series, Exchanging Culture for Flesh. Notorious figures of war and terror go about their dirty business in a post-9/11 landscape, with works bearing titles such as Hellfire Homestead BUSH Wacking Dingo and Let Me fuck You For Oil. According to curator Megan Monte, “Griggs constructs an image through layering subtle with iconic symbols and motifs”. This is a language fluent to Filipinos (expressed with sophistication throughout Passion and Procession). From the groan-inducing word play of billboard advertisements, to the coded symbols of religious imagery, and double entendre of jeepney art, layered meaning is something of an obsession within Philippine visual culture. Griggs is experimenting with this language, but in this series the layers fail to achieve much depth. The provocation feels too easy, with the works espousing commonly held political opinions.

Just one year later, Griggs seems to have found his form. In an adjacent room, large canvases stretched across freestanding frames sit incongruously on checkerboard carpet. Griggs painted The Bleeding Hearts Club in 2006 from photographs taken on the city’s streets, on a scale inspired by the towering billboards of Manila. If Exchanging Culture for Flesh seemed to me, in the words of Paul Keating, “all tip and no iceberg”, then these works run a lot deeper. Realistically painted portraits are overlaid with an anarchic mix of skulls, tattoo designs, religious icons, and emoji-inspired hearts. Here, and in later series, Griggs’ portraits are tough, tender, wholly without judgement, and achieve what all good portraits should, in making the viewer feel curious, conflicted and connected. His scribbles and smears expand the frame beyond the individual to describe something of the world they inhabit, and something of himself.

In Blood on the Streets (2007), one of two video works in the exhibition, a group of children wearing ghoulish masks ride a trolley along a railway line. There is a certain joy watching these children co-opt the railway, but the skull and Frankenstein masks fill the game with menace and seem to pull young life towards decrepitude and death. Griggs made Blood on the Streets after visiting San Fernando during Holy Week, one of the Pampangan towns famous for re-enacting the Holy Cross Crucifixion. In responding to the performative celebrations of Jesus Christ’s death and resurrection, Griggs presents a strikingly original take on Christianity in the Philippines. Where’s Francis (2013) expresses a similar sensibility, morbid and absurd, but this time with a dash more comedy. The two bloodied heads of a couple of extras poke out from the jungle floor. Clearly forgotten by their director, they smoke and chat while awaiting further instructions. The video references the Vietnam War epic Apocalypse Now (1979), directed by Francis Ford Coppola and filmed in the Philippines in the late 1970s. As with Reforma’s Coconut Republic, Where’s Francis provokes considerations of the comings and goings of Americans throughout recent Philippine history.

Griggs’ practice involves strikingly similar modes of collaboration to that of the Aquilizans. Both have produced work in collaboration with “outsider” communities, including prison inmates in city jails, and both have commissioned and reconfigured the work of other artists; the Aquilizans through the Mabini Art Project and Griggs by employing Filipino billboard painters to execute the underpaintings of his works. But there is a critical divergence in their approach to the second mode of collaboration. While Griggs works with billboard painters to achieve a desired aesthetic the Aquilizans place the collaborative act at the centre of their work to negotiate the blurry line between collaboration and exploitation.

A collaborative act also connects two other exhibitions in the Bayanihan program. Alwin Reamillo’s Bayanihan Hopping Spirit House, a bamboo house-like structure, was exhibited first in Balik Tanaw at Peacock Gallery, Auburn, and then in Balik Bayan at Blacktown Arts Centre. Community members came together to transport the work between the exhibitions in a performative representation of bayanihan, the Filipino tradition of communally lifting and moving a house from one location to another. I encountered Reamillo’s work at its final destination in Blacktown Arts Centre, having missed the show at Peacock Gallery and its subsequent procession. Occupying the centre of the main space and heavily adorned with objects, the work overflows with Reamillo’s signature forms and motifs.

While Bayanihan Hopping Spirit House may seem like the cross-cultural equivalent of a big group hug, a closer look reveals the artist’s ambivalence to the collective endeavour. Reamillo’s propensity for incorporating multiple conflicting perspectives within a single work can be seen in his inclusion of the crab motif, a reference to the Filipino term “crab mentality” – picture a bunch of crabs in a bucket preventing any individual escape by dragging each other down. The exhibition text reinforces this ambivalence by noting that the word bayanihan is “often used as a romantic and arguably problematic representation of the Filipino community spirit”. Nevertheless, in linking his participatory art practice with collectivist aspects of Philippine culture, Reamillo caused me to consider cultural explanations for the prevalence of collaborative approaches across the exhibitions.

Reamillo is just one of a number of Filipino–Australian artists to explore their Philippine heritage and culture in the exhibition aptly titled Balik Bayan (a Tagalog phrase meaning “return to country”). While the gallery spaces present an interesting mix of perspectives from the Philippine diaspora, the real strength of Balik Bayan is a program that integrates visual art, film, performance, music, and a range of participatory activities, from Leeroy New’s work with community members to transform local waste into sculptural installation, to Club Ate’s performance party in celebration of queer culture. The multi-arts agenda of Balik Bayan not only aligns with increasingly popular approaches to programming, but more importantly reflects a long history in the Philippines of integrating art forms through performative cultural activities. The curators’ approach suggests a high level of connectedness with the local Blacktown community, which is home to one of the largest populations of Filipino–Australians in the country.

Arts programs aimed at promoting and celebrating a particular culture inevitably run the risk of pandering to dominant cultural paradigms, of subsuming individual perspectives in the attempt to promote a collective identity. While the term bayanihan may have come to reflect romanticised notions of collectivism in Philippine culture, the Bayanihan Philippine Art Project successfully avoids simplistic expressions of a collective cultural voice. Instead, the project presents a series of exceptionally well-curated exhibitions and associated activities, featuring artists from a range of contexts who are all in some way connected to the Philippines. The result is a program that collectively demonstrates the strength and diversity of Philippine contemporary art. Conceptual threads, visual languages, and collaborative approaches bind some artists and exhibitions to others. But beyond that, very few generalisations can be made.