As I make my way to the National Gallery of Singapore to view the much talked-about Yayoi Kusama retrospective, there is a heaviness in the air. Midway through the journey, it begins to rain. Globs of liquid pelt the windscreen of my taxi, burst upon contact with the smooth glass surface, and trickle downwards, discharging a visual and sonic rhythmic pattern not unlike a Yayoi Kusama painting.

On arrival I walk into the expansive courtyard entrance, which has been overtaken by round yellow spheres with black polka dots. Dots Obsession (2017) is made up of giant inflatables hanging from the ceiling, as if descending from the heavens, an allusion encouraged by the clear glass panels above with an open view of the sky. People are preening and posing for “selfies” and group pictures under the mammoth globes. The staircase leading up to the second level is awash in light yellow, embellished with bold, blue dots of varying sizes arranged along patterns of meandering lines, suggesting the familiar forms of Kusama’s pumpkin motif. Humans are going up and down the stairs, to varying degrees of directed purpose, as if taking part in some kind of aleatory performance, or staged “happening”, discreetly engineered from afar by Kusama herself. A poster of the exhibition hanging from the second-floor balcony features the artist in her signature red wig in front of the painting from which the exhibition takes its title, Life is the Heart of a Rainbow (2017).

This is an ambitious presentation of over 120 works, spanning almost seven decades, from Kusama’s early years to recent works not previously exhibited. The journey begins with paintings from the 1950s, in the first section (Gallery A). I am struck by the hermetic darkness and small scale of the first five works on display – Plaster Spirit (1954), Flower (1952), Self Portrait (1952), The Night (1953) and The Island (1953) – are a stark contrast to the bright, expansive and playful mischief that envelopes the welcoming entrance. Melancholic, even morbid, these works introduce the unique sensibility and motivations of Yayoi Kusama that distinguish her from the more conventional schools of practice.

In 1948 Kusama entered the Kyoto Municipal School of Arts and Crafts, to learn the Nihonga traditional Japanese style of painting. But, unhappy with the restrictions imposed on artistic style and the insistence on obeisance to hierarchical relationships between master and student, Kusama rebelled and withdrew. These paintings clearly communicate a sense of this oppression, disenchantment and defiance. They are condensed and acrid, and seem to convey repressed intimations to lifelong thematic focus on what Kusama refers to as her “neurosis”.

In Self Portrait from 1952, a fiercely penetrating single eye drawn in thick black lines stares at me amidst a halo of finger-like projections bedaubed with small white dots fanning outwards from a thick-stemmed base. I am transfixed, it is as if the fiercely penetrating gaze is establishing a kind of omniscient authority over mine, from the depths of its lofty isolation, hypnotically directing my sensory and cognitive responses, and drawing me into its manic realm of juxtaposed obsession and obliteration. As an autistic person, eye-contact is often difficult for me, yet I am fascinated by the eye as a sensory channel, and its symbolic meanings.

Many autistics report that eye-to-eye gazing is challenging because there is too much visual stimulation for an intrinsically detail-oriented mind. Instead of processing information quickly to extract general, superficial meaning, our minds easily become overloaded by the volume of emotional and physical details. But the eye in Self Portrait is not pressing upon me an interactive social agenda; instead, its insistent stillness penetrates the carefully built external walls of my mental state, as if it is assessing my gaze, and I am fascinated by this quietly intense form of reciprocity.

I am looking at and experiencing Yayoi Kusama through the lens of my own neurodivergence, a predisposition of function that deviates from the neurotypical norm. It is not a lifestyle choice or trendy point of view, like an instrument or accessory that one carries around to peruse at will. For me, this is a dynamic lived and living experience of being. As an autistic person, I perceive and respond to the world from my own paradigm. In so doing, I am not intending to assert an autism diagnosis onto Kusama, but merely to present novel associations and generate candid dialogue in an as-yet relatively unexplored territory. In relation to Kusama, not much is said about any specific diagnosis. She merely uses the term “neurosis” – and occasionally the word “psychosis” crops up – to explain the excruciating agony and wondrous delight that comes from seeing the unseen, hearing the unheard, and interpreting the world from a parallel-embodied perspective.

Immediately following the five early paintings are the Infinity Nets, a defining body of work, and a repeated motif of Kusama’s in which the weave of the net is a starting point in her execution of automatic drawing and painted forms. The growth of these motivic cells, relentlessly expanding outwards to fill a larger and larger space, is a hallmark of Kusama’s early years in New York, leading to the development of the robust symmetry for which she is so well-known. Meticulously engraved and tightly woven, they emanate a dizzying effect of continuous expansion and preoccupation with detail.

Moving between the works, from the brightly coloured to the stark white, and monochromatic, each piece creates reiterative imprints on my mind. Fully immersed inside their realm, I follow each evolving reiteration and expansion until they literally crawl out of their canvas fields, just as Kusama describes it, to engrave themselves onto the corporeal consciousness. It is an embodied feeling, not merely a figment of pure imagination, but a stark physical manifestation of the perceptual and cognitive function of the autistic or neurodivergent mind. My very skin begins to tingle from an invasive sensation.

Death of a Nerve (1976) is a striking installation of mixed media and stuffed fabric. It’s presence among the painted works in this exhibition prefigures the later soft-sculptures. This work shares an organic association with Self Portrait in its writhing animated depiction of miniscule components of human biology. It is as if Kusama has turned inside out and dramatised the cellular realms of bodily existence. These coils of textured material, a 10,000 cm stuffed snake-like creature that winds, drapes and hangs against a white background, appear spent and tepid like a languishing, dying nerve, or grotesque, forlorn extension of the artist’s soul within this almost Artaudian theatrical capsule.

In Antonin Artaud’s “Theatre of Cruelty” the focus is on laying bare, without niceties or window dressing, the dark and grim nature of human existence. The method is highly confrontational, and directed at the senses rather than the intellect. Death of a Nerve bears echoes of similar deliberations on the grotesque, relating without prosaic narrative the sensory poetic of dying – not as a pretty, heroic symbol but as a pathetic, tangled, limp devolving entity. I can almost hear the sound of a wailing, wordless lamentation, slowly trailing off into still silence.

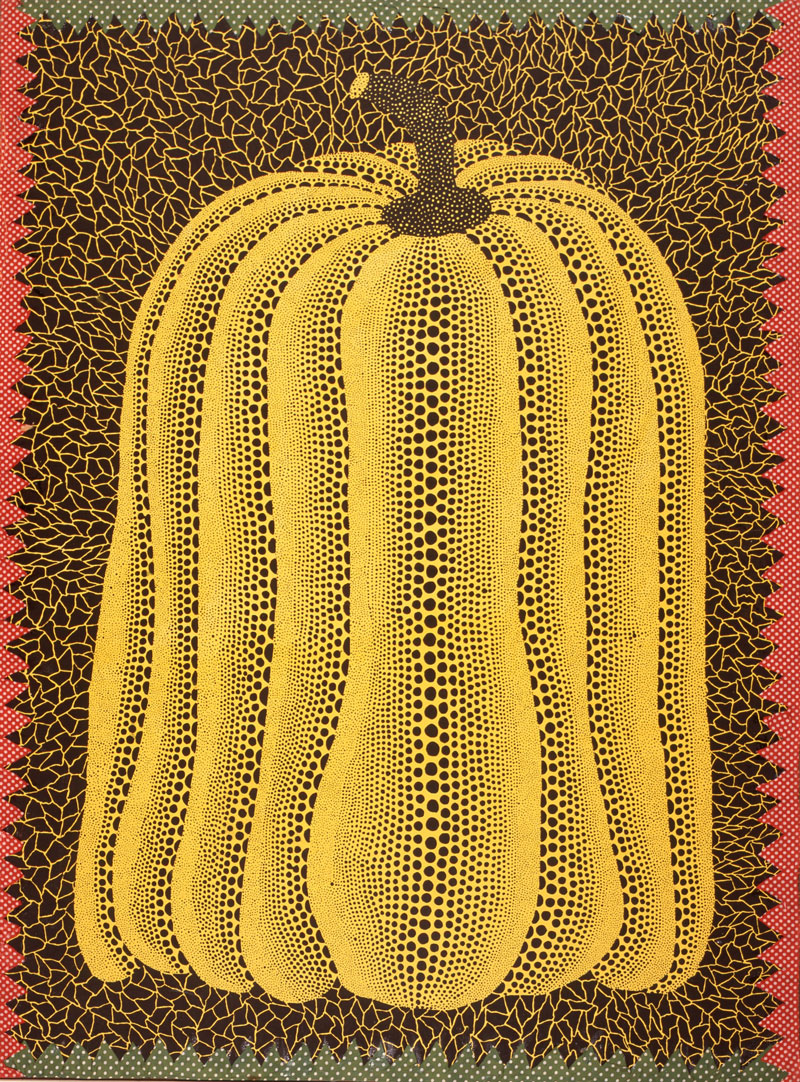

Following the dots and nets, the pumpkin is another of Kusama’s favourite symbols. As she discusses in her autobiography, the first time Kusama came face to face with a pumpkin was in elementary school. Her grandfather had taken her to a seed-harvesting farm, and while exploring the fields she came upon a pumpkin “the size of a man’s head”. As she reached out to touch it, the pumpkin began to speak to her “in a most animated manner”. Kusama was beguiled by the pumpkin’s “charming and winsome form”, “generous unpretentiousness”, and “solid spiritual balance”.[1] Her personal descriptions of the pumpkin are important, as they reveal an intimate relationship with objects and elements that reflect an intuitive empathy, bestowed upon the pumpkin to engage a sentient and vibrant sense of communion.

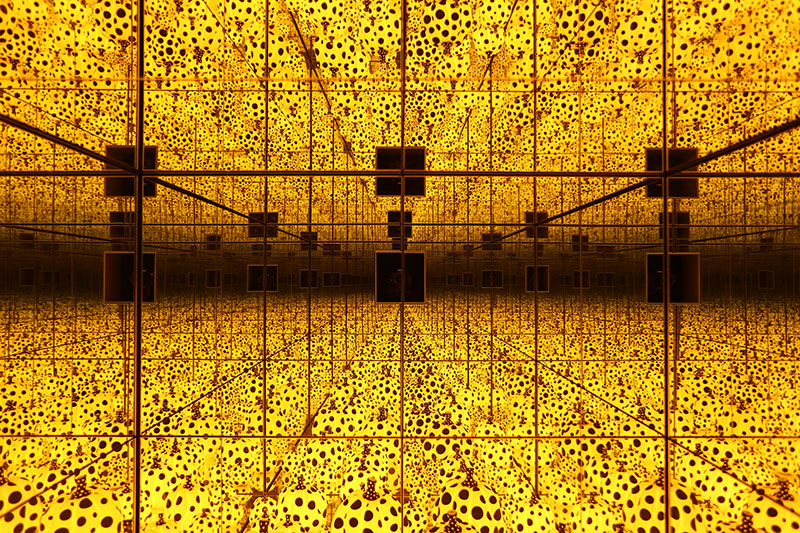

I am beginning to feel a gentle, yet intense, affinity with Kusama. Peering at the red and green serrated fabric framing the 1981 work titled, Pumpkin, my fingers involuntarily twitch and wiggle, wanting to touch the edges of the material, but it is protected from my prying by a thick glass screen. The background is black, covered with an interlocking netting grid, the same motif seen in the Infinity Nets. A bulbous yellow pumpkin radiates from the centre, growing fold upon fold, expanding towards the edges in black polka-dotted motion. The largesse of the motif is captured in the expanded field of her mirrored installations, such as The Spirits of the Pumpkins Descended into the Heavens (2017).

On encountering the first of these installations, I mingle with the procession of tittering humans congregating inside a yellow and black polka-dotted room, gazing at our reflections on the mirrored box in the middle of the room, cameras clicking away. I ascend three small steps and peer into the hole in the mirrored box to encounter the dizzying yet mathematically ordered array of pumpkins. A combination of yellow and black dotted pumpkins and mirrors, this installation cleverly transports the viewer into a fiery three-dimensional field of infinity. After a mere few seconds, my bodily reflexes lead me staggering away from this sensory assault. It feels like I am locked into a surreal eternity of fascination and terror, a tension-filled polarity that Kusama herself expresses over and over in her art and writing.

There is a foyer between this exhibition space and the next, graced by two giant pumpkin installations, one yellow and the other white, each covered with small reflective tiles. These stolid, phlegmatic declarations are a stark contrast to the volatile impact of the mirrored installation, and act as a kind of buffer, like a sensory winding-down after the intensity of the first part of the exhibition.

Mental conditions such as depression and anxiety are a logical outcome of the conflict that arises from being forced to conform to standardised expectations of behaviour and the alienation that arises out of departure from the norm. Unsurprisingly, commentators and observers tend to buzz around the clinical pathology of Kusama’s state of mind, given that Kusama speaks openly about her mental struggles and chooses to live within a psychiatric facility. Kusama grew up in a time when psychiatry was not in its infancy, but still an inexact science.

Today, we have the complex field of neuroscience to examine the different phenomena. But it was not long ago that psychiatrists were misdiagnosing conditions like autism, employing drastic electric shock therapies, and sending countless autistic persons to be incarcerated in mental institutions. Coincidentally, the terms “neurosis” and “psychosis” were commonly used with reference to autism, and what is now associated with an enhanced perceptual ability that used to be mistaken for “hallucinations”.

It is only in this 21st century that an understanding of neurodivergence has achieved a more radical shift in recognition and acceptance. Can it be that the root of Kusama’s “neurosis”, seen in the light of today’s advanced understanding of neurology, is actually an unpretentious, lucid and acute ability to notice subtleties and the autistic trait of detail focus?[2] It is in response to these sublime communicative interconnections and mannerisms, uncommon among the neurotypical majority, that I have focused my own research on autistic “elemental empathy.”[3]

New research also indicates that, for some, “hallucinations” may even be linked to an auditory phenomenon that has nothing to do with psychosis.[4] In this study, researchers discover that some brains are more acutely aware of voice inflections, and are able to pick out voices from very noisy and busy recordings. These same people are also more inclined to hear speech even when there is none, due to a “tuning” in their brains towards vocal inflections. Could Kusama’s accounts of neurosis, hallucinations and “hearing voices” (e.g. pumpkins speaking) have actually been a confluence of all these anomalies, not clearly defined at the time?

The second section (Gallery B) of this exhibition presents Kusama’s distinct concepts of the body and “obliteration.” This is where Kusama’s neurodivergence matures thematically and becomes more obviously cogent in her praxis. The majority of neurodivergent people are faced with the need to create personalised self-intervention strategies in order to cope with the demands of living in a neuronormative world. Desire to create meaning from what is pronounced “meaningless” by an un-sympathetic domain is a strong driving force for survival. Kusama’s coping strategy is to confront her own fears via artistic expression. One of the ways she does this is to accord them concrete, multi-sensory form.

I enter Gallery B through a curving corridor, walls and ceiling bedecked with large convex mirrors, where the self gets lost inside its multiplications. Moving through the exhibition to arrive at Kusama’s soft-sculptures, these works come across as enigmatic organisms that invite more than mere visual engagement, and it is a pity I am unable to touch any of them. Kusama first began to create these symbols of phalluses as a way to express her own fear of sex and her repulsion for the male sexual organ. Churning out these objects of her innermost fears in the thousands, and transforming them into familiar things helped to debilitate their power over her. Kusama called this therapeutic mitigation process, “Psychosomatic Art”.[5]

Another obvious process of “obliteration” is her signature motif of the polka dot. Evincing a sense of cheer and perky exuberance, these polka dots expunge fear and exorcise “egoistic” exaltation in an expanded sense of the Self that fills the space. The ego is another topic worth analysing in relation to autism. Non-autistic observers have ascribed to autism extreme egocentrism and self-absorption, attributed to so-called impairment of empathy. Confronting these assumptions, recent research reveals that autistic persons possibly possess a surfeit of empathy,[6] and a different way of connecting with the world,[7] which can cause individuals to react in idiosyncratic ways. As a result, many autistics report a habit of over-thinking the conundrum of Self in juxtaposition to the Other, which no doubt contributes to the misunderstanding. Borrowing from this tension-filled scenario, could it be that Kusama’s desire to obfuscate the self is a coalescence of mistaken “egocentrism” (guilt-filled and fragmented as it is) and empathy fatigue?

Tucked into a small separate room are photographs of Kusama’s experimental forays into sex and the body. There is a sign demarcating this space for visitors aged over 18. But examining these images from the point of view of the 1960s, they come across as remarkably lacking in overt sexuality or sensuality. Instead, a sense of isolation settles over my viewing. Kusama is the solitary voyeur, instigator and director of these social arrangements. She never takes an active part in the writhing libretto: she is the puppet-master. Once more, my mind draws an association with the “gatecrasher” or bystander persona of the autistic or neurodivergent person, investigating and analysing the normative realm with great interest and distancing perplexity.

Infinity Mirrored Room: Gleaming Lights of the Soul (2008) is yet another amazing physical construction. The immediate sensorial impact is so potent that vertigo nearly overtakes me as I momentarily lose all attachment to smell, taste, touch and hearing. This dissociation lasts a mere split second, but it sends a sharp chill down my spine. Very quickly, I am conscious again, and now utterly enthralled at being enveloped by thousands and millions of tiny, coloured dots of light. A pure, unrestrained marvel, not only for the eyes, but a powerful trigger to the senses, such that I can even hear the soft zinging of the lights, a microscopic chorus of contrapuntal conversations.

My heart is racing, my skin feels compressed by the density of the atmosphere, and a light metallic taste settles on my tongue just as the door opens and I am ushered out of this magical wonderment. Is this Kusama’s “hallucination” or my own? This hypersensory reactivity and detail-focused cognition is normal for me, and my affinity for Kusama grows.

The third section (Gallery C) is where the new and current works are housed. Kusama’s dots appear everywhere in her paintings, defining their pattern, form, movement, meaning and cohesion, and made all the more poignant in their multi-dimensional invocations. With All My Love for the Tulips, I Play Forever (2013), is a potent installation in this category. Oversized metal and fibreglass tulips stand twisting and turning on rounded platforms as colourful red, blue, yellow, green and purple dots that cover every surface in the room, including walls, floor and ceiling. Where do the tulips begin and end? The imminent threat from their looming stature is obliterated by the dots, lending a quirky jocund fervour to these grotesque figures.

Kusama persistently excavates the subtle minutiae and renders them in stark, explicit and overblown formation. An autistic friend, Timothy, sees this installation as “tulips interpreted in its pure form”, and revels in Kusama’s dots: “A dot looks like an atom. When we wake up, sometimes, when we open our eyes, we see many small dots. The dots spread in the vast world and it fills our world. I immediately made a connection with the dots.” As I look at the throngs of people merrily posing for photographs, I wonder what kinds of connections they are making with the dots, and if there is more to it than the routine drive to narcissistic self-expression?

In 2009 Kusama began work on the colossal series, My Eternal Soul, an ongoing production that has resulted in over five hundred paintings to date. Twenty-four of these are presented in this exhibition, some never before shown. Brightly coloured and confrontational, the imposing works contain Kusama’s distinct motifs of eyes, dots and lines, and the centerpiece bears the name of this exhibition: Life is the Heart of a Rainbow (2017). My mind registers the unique nuances of each da capo, and I fall prey to sensory overload. Kusama’s recapitulations are deceiving, they are not repetitive wallpaper motifs that fade into the background of consciousness, but rather tiny entities, each possessing their own unique arresting nuance.

There are so many of them – clamouring for attention all at once – that my brain becomes weary, devoured by my own innate pursuance of the minutiae, observing pattern and embracing the multisensorial. To my mind, Kusama is detailing the molecules in the infinite universe, conversing with every cell in my finite containment, while dancing in the interstices, touching and connecting the intangible with the palpable forms of embodied expression. Kusama’s repetitious style brings to my mind what is commonly called “perseveration” in autism studies, viewed by the normative as an “impairment” to be corrected or eradicated, but which autistic persons would explain as “new ways of seeing the excitement in the things that (others) take for granted.”

Initially, I stand warily at the threshold, a curious spectator gazing into the world of Yayoi Kusama. Soon, however, I find myself submerged, fascinated at the fervid tension between pain, passion, obsession, obliteration, sobriety, mischief, fear, brazenness, imprisonment and release – all ironic juxtapositions of a living expression so closely aligned to my own. Perhaps the most haunting work in this prodigious experience is the video in the middle segment of the show, Song of a Manhattan Suicide Addict (2010). Etched into my memory is a diminutive figure of a little girl, transfixed, in rapt attention, listening and watching as Kusama sings in Sprechstimme style, the words of her poem.

Swallow antidepressants and it will be gone

Tear down the gate of hallucinations

Amidst the agony of flowers, the present never ends

At the stairs to heaven, my heart expires in their tenderness

Calling from the sky, doubtless, transparent in its shade of blue

Embraced with the shadow of illusion

Cumulonimbi arise

Sounds of tears, shed upon eating the colour of cotton rose

I become a stone

Not in time eternal

But in the present that transpires

Footnotes

- ^ Yayoi Kusama, Infinity Net: The Autobiography of Yayoi Kusama, (trans. Ralph McCarthy), Tate Publishing, eBook location 659.

- ^ See Laurent Mottron, Michelle Dawson, Isabelle Soulières, Benedicte Hubert, and Jake Burack, “Enhanced Perceptual Functioning in Autism: An Update, and Eight Principles of Autistic Perception,” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, January 2006, Volume 36, Issue 1, pp 27–43.

- ^ As discussed in my PhD dissertation: Dawn-joy Leong, Scheherazade’s Sea: Autism, Parallel Embodiment and Elemental Empathy. UNSW Art & Design, 2016.

- ^ Ben Alderson-Day, César F. Lima, Samuel Evans, Saloni Krishnan, Pradheep Shanmugalingam, Charles Fernyhough, Sophie K. Scott; “Distinct processing of ambiguous speech in people with non-clinical auditory verbal hallucinations”: https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awx206.

- ^ Yayoi Kusama, Infinity Net: The Autobiography of Yayoi Kusama, eBook location 376.

- ^ Kamila Markram, Henry Markram, “The Intense World Theory – a unifying theory of the neurobiology of autism,” Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 2010; 4: 224: Online: doi 10.3389/fnhum.2010.00224

- ^ Ralph Savarese, “I Object: Autism, Empathy and the Trope of Personification,” Disabilities Studies Initiative, the Centre for Mind, Brain and Culture, and the Hightower Fund present, 19 February 2014, Lecture.