.jpg)

The point is not that I am a collection of identities, but that I am already an assembly, even a general assembly, or an assemblage.[1]

Brook Andrew is a transdisciplinary rather than cross or inter-disciplinary artist. By this I mean his art is not a conversation between mediums or styles or disciplines, like some Socratic dialogue. Rather he moves between these things in ways that blur traditional disciplinary boundaries. Like Fred Astaire, Andrew seems to know all the moves but like a collective line of cabaret dancers, the various media and stylistic tactics combine into a coherent collaborative voice that is greater than any single one. This trans mode is on full display in the carnivalesque survey of his work at the NGV, The Right to Offend is Sacred. Its transaesthetic along with its transcuration is the most effective channeling of the contemporary trans zeitgeist you are likely to see for some time.

By trans I don’t mean its current derivation from transgender – though those looking for issues of gender will not be disappointed – but a more general trend apparent in nearly all fields in which the desire seems to be collapse traditional hierarchies and binary relations into what I have called elsewhere a trans Ideal – a perpetual openness without closure.

.jpg)

If for some time Andrew has been a leading practitioner of the trans, in The Right to Offend is Sacred not everything melts into the airy realm of the trans Ideal. This is because its wild mixings are grounded in the legacy of colonial culture: the memories and traumas of colonialism hold the delirium of imagery in various orbits. Further, these memories read like dreamscapes, as if the exhibition is a projection of their mixing in Andrew’s unconscious. In this respect The Right to Offend is Sacred is a Dantesque journey through the centre of Andrew’s unconscious world except he doesn’t emerge at the antipodes to find paradise and rejoin his beloved Beatrice. Staying in the underworld, he inhabits what Gordon Bennett, whose legacy Andrew can here surely claim, called a “psychodrama”.

Like Bennett, Andrew has a sharp sense of design and movement, and with recontsructed recontextualised appropriations moves between existing text and imagery as if they are the same thing – which they are in the media world. But the results of Andrew and Bennett’s transaesthetic could not be more different. Bennett’s work has an existential weight – even its humor is black – whereas Andrew’s work has a lightness of being even in its darkest themes. In this respect, Andrew seems to draw as much if not more from the transaesthetic psychodramas of Tracy Moffatt and Destiny Deacon – and one might add Juan Davila and Rea. Echoes of their different practices resonate in The Right to Offend is Sacred, as if they comprise of a hidden personal archive of spirit dancers that Andrew choreographs.

More than almost any artist I can think of today, Andrew takes the transaesthetic to a new level of intensity. As with Bennett and these other artists, the transaesthetic is a cure for an original loss or expulsion. Rather than seek to regain paradise or innocence, Andrews embraces the freedom of the trans as a gift:

There’s a thing about being mixed blood. I think we are special in this full-on black against white hardline dispute. I just woke up one day and thought to engage in a world as I do as an artist; it is important to acknowledge that we come from mixed ancestries.[2]

While ostensibly a survey of his work, it is much more. The success of this exhibition rests less with the presence of individual works – which nevertheless is fabulous – and more in its curation. For someone who doesn’t know his work it would be easy to mistake the exhibition for an installation. Indeed, it would not be a mistake, as curation propels all his work – even that made 25 years ago – into the singular present moment and scene of the exhibition, as if it is some vast transfiguration machine that breathes its own life into things, including his previous work.

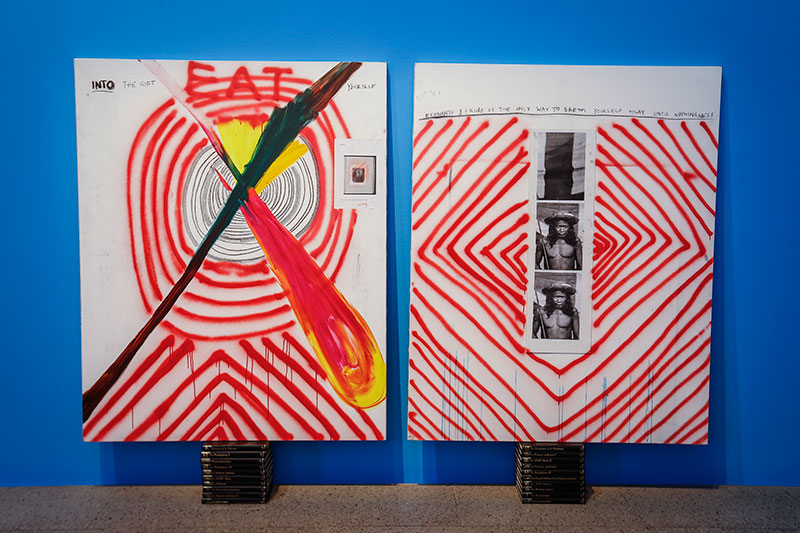

In The Right to Offend is Sacred Andrew’s transaesthetic becomes a curatorial imperative in the Enwezor manner.[3] Quoting Judith Butler (see the beginning of this essay) Anthony Gardner aptly called Andrew’s works “assemblages”. Many are in a quite literal sense in that they assemble all manner of documents and objects in vitrines and on walls. But Gardner means more than this. As if caught in some fractal geometry, these assemblages transmutate across the galleries like cells continuously dividing and multiplying into a larger assemblage.

What grounds the reifying effects of this transfiguration is that this assembling never becomes an abstract movement in its own right. They are assemblages of archives, histories, ideologies, cultures, materials, designs, media, motifs, concepts, memories and forgettings. And, as Gardner points out, of viewers – sweeping them all up into some vast impossible translational exercise. Impossible because translation can never be true to the original but at the same time the original, which always abides in that foreign country called the past, can only speak to the present through translation.

This sense of an inevitable deferral or interruption is built into the structure of the assemblages. While they have an underlying sense of order, their potential hegemony is never quite complete or realised. “This isn’t always”, Gardner says, “a harmonious exercise”.[4] There is a failure, or more accurately refusal, to get to the essence. Something spills over, and there is invariably an excess, a clash, not to mention undertows and dangerous crosscurrents that pull us back to earth, in this case, to the archive and its reverberations of the past in the present.

.jpg)

Andrew’s transits through the archives of colonialism are not aimed at setting things straight or establishing a new order, but at discovering a postcolonial ethic. The large number of archival portraits of people from across the world, all images of people now dead who lived in places and times that are foreign to us stare back from their place and time at us as if refusing to be buried – “as the dead surround the living, their stares can feel more like reproaches than attractions”. Their very number, lined up in rows across the centre of the central room demands says Gardner, quoting Butler, “a politics of alliance … an ethics of cohabitation”.[5]

But more, this very excess of colonial witnesses pulls us into an undertow of forgotten and repressed histories. This immersive transspace, which rides a thin line between spectacle and carnival, continuously pushes us against the cultural differences and historical traumas of colonial cultures, not in recrimination but like Walter Benjamin compelled by a duty to “wrest tradition away from the conformism that is about to overpower it.” To “have the gift of fanning the spark of hope in the past”, Benjamin wrote, requires you to be “convinced that even the dead will not be safe from the enemy if he wins.”[6]

Footnotes

- ^ Judith Butler quoted in Brook Andrew: The Right to Offend is Sacred, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 2017, p. 90.

- ^ Quoted in Judith Ryan, ‘Aesthetics/Medium/Process’ in Brook Andrew: The Right to Offend is Sacred, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 2017, p. 6.

- ^ See Ian McLean’s review ‘Postwar: Art between the Pacific and the Atlantic 1945-65’, published 14 November 2016: https://www.artlink.com.au/articles/4547/postwar-art-between-the-pacific-and-the-atlantic-/.

- ^ Anthony Gardner,

- ^ Anthony Gardner,

- ^ Benjamin, Walter, ‘Theses on the Philosophy of History’ in Hannah Arendt (ed), Illuminations, Bungay, Suffolk: Fontana, 1982, p. 257.