When you search the term “digital art” in a library catalogue it suggests that what you really want is “digital art mart”. This banal reduction to the consumer marketplace is indicative of the status of digital art today, dragged from its heyday when the electronic arts inspired Marshall McLuhan to claim that the medium of electronic art was so powerful that it was the message. Today, this prophecy seems an understatement. While McLuhan was able to maintain a critical position outside of electronic arts, in the Post-Internet environment the digital is so pervasive in our everyday life that an outside position is impossible.

This shift is particularly evident within artistic practice since the 1990s when artists first began to explore in earnest the creative potential of the digital medium and the Internet. Since then, “net art” or “electronic art” has mutated into the ubiquitous catch-all of New Media Arts; the internet and digital media have for artists become a tool that is as habitual as mark-making or form-building with traditional media. By the mid 2000s, Post-Internet art seems to have absorbed and summarised these shifts. But in the last few years, the rise of Post-truthism has given us cause to critically re-examine the seamless grip that technology has on our media environment.

The exhibition Digital: The World of Alternative Realities curated by Charles and Leah Justin of the Justin Art House Museum (JAHM), could be seen to take up this thread. Their personal and locally focused collection of works sits outside of conventional versions of Australia’s recent art history. There are some big name artists, and some relatively unknown artists, collected according to a very subjective and intuitive methodology. The works are now housed in a beautifully designed house museum in Prahran, Melbourne, which is open to the public by appointment.

The JAHM Collection encompasses a wide range of works across all media, and yet for this exhibition the Justins chose to highlight “digitally generated artworks in formats from prints, photography, sculpture and video.” Whilst the curatorial rationale for this exhibition seems limited to an examination of works created using digital processes and includes work by nineteen mostly-male artists, the choice of Professor Tim Flannery as author of the accompanying catalogue essay suggests an underlying rhetoric of anthropological or environmental imperative.

In his essay Flannery weighs the impact of digital technologies on the environment, as embedded within the Earth itself. Flannery refers to mother “Gaia” as being well wired with digital sensors measuring her “nervous system”.[1] This close listening to the earth through technology is our primary irrefutable tool in the fight against climate change deniers. The evidence offered through satellites, soil probes and oceanic buoys maps out this terrain with statistical data, overlaying the material actuality of the Earth with a digital representation of water, earth and atmosphere.

Inevitably the source of this information, available on the Internet becomes vulnerable to political wrangling and false representation – either part fiction, all opinion or thinly veiled commerce. And so climate statistics are subject to endless computer re-modelling, political manipulation and reinterpretation. The data itself becomes a meta-reality that is distanced from the actuality of the planet, and is instead presented as a reflection of the rhetoric of the user – in other words, a simulacra of itself.

In Simulacrum and Simulation (1981), Jean Baudrillard, a pioneer theorist in electronic and digital arts, conceived of the hyper-real digital context as “a gigantic simulacrum – not unreal, but a simulacrum, that is to say never exchanged for the real, but exchanged for itself, in an uninterrupted circuit without reference or circumference.”[2] For Baudrillard, the fact that simulacra had replaced representation in contemporary society was a harbinger of our demise. Today this operation is the norm.

Digital: The World of Alternative Realities seems to highlight this phenomena, where the real is no longer privileged; not only is the environment subject to data manipulation and fact upended as fiction, artists are becoming increasingly irreverent in their use of digital technologies. This inclination towards interdisciplinary practices within a Post Internet context is part of a cultural shift which artist Artie Vierkant points out has cast artists in “a role more closely aligned to that of the interpreter, transcriber, narrator, curator, architect.”[3] This reassignment of the artist as an interpreter or transcriber of the digital world is a major theme within the exhibition. Artists such as Stephen Haley, Debbie Symons, Michael Candy and Greg Neville each take information found on the Internet and process it through their practices.

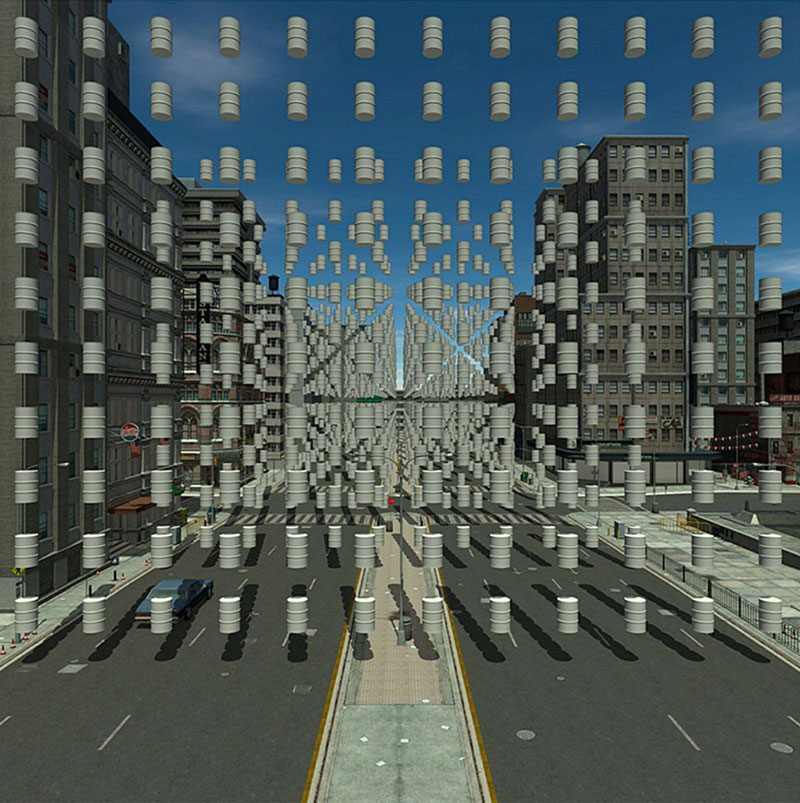

Stephen Haley’s works in this exhibition One Second (oil barrels 1146), Vanishing Point (2008), One Second (plastic bags 31688) (2010) and Driveby (2011), all take advantage of the consumability of digital images. To create these video and print works Haley purchases stock images and scenes from gaming and architectural sites and configures them in imagined scenarios. This process highlights how the digital image, stripped of meaning, has become an infinitely malleable simulacrum. Through reappropriation, the image of a city street, barrel or plastic bag purchased through these websites can be deployed in ways that are socially and politically antithetical.

Likewise, Greg Neville in his work GoooOg (2012) uses satellite images sourced from Google Earth and reconfigured as mirrored, symmetrical compositions. These configurations treat the terrain as raw material, offering a new order completely unrelated to the towns and cities represented in the sourced images.

In both Neville and Haley’s works the terrain depicted is irrelevant, the material reality of the stock or Google Earth image is discarded in favour of the artist’s creative schema. This is not appropriation, it is more like Baudrillard’s retelling of Borge’s fable of the cartographers who drew up a map so detailed that it covered the land represented so that the “territory no longer precedes the map.”[4]

While these artists tackle their own shifting relationships with the rapidly-changing cultural material available through the Internet, other artists in this exhibition are less concerned with the cultural shifts, and instead focus on the ability of digital technologies to manipulate reality so that it can reveal new insights into our future, or critically reappraise the present moment.

Daniel Crooks, who has two works in this exhibition, No.10 (neither here nor there) (2012) and Pan No.7 (strange attractor) (2010), has pioneered a method of spatialising the two-dimensional image. He is able to break apart the image file through stretching the width, height and depth of an image into a state of abstraction, by manipulating duration. In Pan No. 7 (strange attractor) (2010), Crooks uses digital technology to get inside the moving body. The bodies in this work appear liquid as they morph in and out of each other and the surrounding environment. This fluid connection with the world seems to present an out-of-body, spectral dimension in which humans are not confined to their bodies, nor buildings by their form. Crook’s work describes this life of forms as a kind of digital cyborg, presenting an extended view of human behaviour.

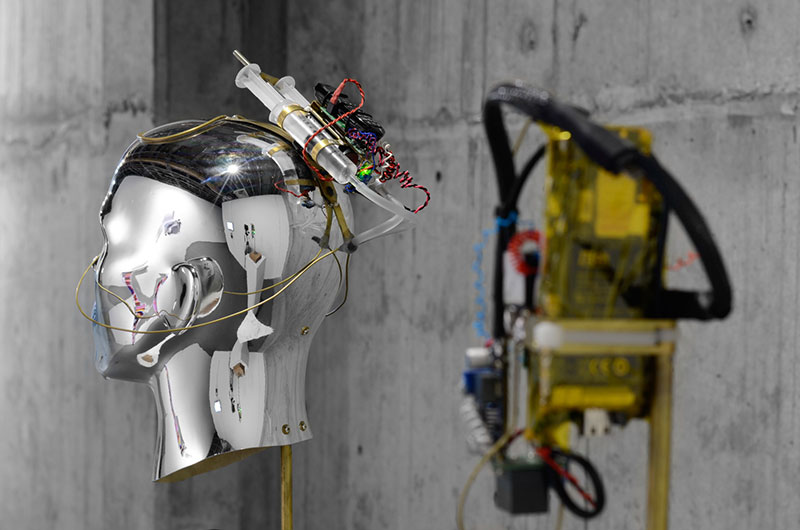

Likewise, Michael Candy’s work occupies the junction between human and machine. Candy’s cyborgian vision involves the fusion of the human quality of Empathy onto an inanimate object. For Digital Empathy Device (2016) Candy created a small robotic tear-dispensing device connected to a live website that monitors casualties and bombing raids in Syria. In 2016, Candy travelled to France and concealed this device behind the head of a statue of “Marianne”– a symbol of the French Republic and égalité, which is situated above the civilian memorial of the 2015 Paris Attacks. Here, as each air raid, bombing or attack occurs in Syria, Marianne can be seen to weep, as the declaration of equality for all becomes more divisive. Originally a gesture of peace and solidarity, the notion of égalité is collapsing beneath the weight of the increasingly popular anti-immigration politics of division in France (that is also engulfing the Western world).

The deployment of digital processes to engender political change is present across several of the works. Jiang Pengyu’s Unregistered City No.7 and Yang Yongliang’s Snow City Quanternity 3 (2009) both employ Photoshop image manipulation software to depict dystopian realities, and the reckless environmental degradation the artists have witnessed in their own lifetime. Yang Yongliang uses delicate digital image manipulation to highlight the social and environmental fallout from China’s rapid pace of change by drawing on the delicate aesthetic of traditional shanshui (landscape painting), and replacing mountains with clusters of high-rise buildings, streams with busy highways, and the Chinese crane with the construction cranes that now dominate the Shanghai skyline.

Stephen Haley’s work’s One Second (oil barrels 1146), Vanishing Point (2008), One Second (plastic bags 31688) (2010), variously chart the number of barrels and plastic bags produced in one second. The bags hover mid air before a vast orange sun that sets behind a molten mound of black plastic bags; and the barrels float in front of an urban city scape like Donkey Kong barrels awaiting a player. The sheer number and incessant repetition of these images blocks the view, and our ability to grasp the entire situation.

In the context of this exhibition, drawing on an environmental consciousness, it is clear that these works are trying to make political statements. But these works call into question the overall efficacy of digitally manipulated imagery as a political tool. The success of works that employ digital technologies for political outcomes, is dependant on an audience that perceives these images as political rather than simply as material practices, in an age where digital media has so pervasively flooded our visual field, and perhaps has more to do with the circulation or distribution of images outside of this realm of art. In context, as artist Richard Grayson writes; “The post-internet art arena becomes a place where these ideas are represented and aestheticized as affectless signifiers, as representations of themselves and as weightless commodities.”[5] It is fair to say that such works of digital art are rather more anaesthetising than activating in engaging the viewer; the simulacra affect has effectively deactivated the digital image.

.jpg)

Gordon Monro’s extraordinary experiments with data, further illustrate the abstraction of meaning that has occurred. The works Difference Engine 4.02a and 4.02b are digital prints that have been created by computer programs that emulate an evolutionary process, “where small patterns are evolved under the pressure to be different from one another.”[6] The computer programs appear like a small network or mind map, with interconnecting circles of equations. The artist then feeds these through a program, which translates the network into an image. The resulting product is a beautiful cross-spectrum, multi-coloured image, where code has been transformed into its visual representation. Monro’s process brings something into existence that is not real. Interestingly some of the networks do not result in any visible image, as if Monro has created a population of simple cyborgs that maintain a kind of self-regulating process of natural selection.

This work brings into focus the possibility that what has been created through our digital and web based innovations is now alive. Being “alive” in a digital sense means that data is self-generating and animated. As Flannery writes in his essay, DNA is akin to a computer program, holding immense amounts of data and the RNA is what activates it; “the proteins that our bodies are made of and whose blueprint is encoded by our DNA, are not fabricated by the DNA blueprint itself, but by “carrier” RNA. It is axiomatic that digital information can only ever be a blueprint for something, which means that there must be something between the digital data and the product – RNA.”[7]

For the digital world to come to life it needs a host, “a carrier”. It is clear that the digital world now lives intermingled within our every interaction, probes our atmosphere and monitors our vitals. We are the RNA to digital’s DNA, and this exhibition brings to light the implications of our seamless reliance on technology. Historically, the earliest computers were huge, room-size creations, so overpowering in an actual, material and physical way, but today the hold of the digital is invisible, omnipresent and reflexive. We have internalised the digital as an embodied state. It has become biologically and psychologically embedded within us, transforming our interpersonal habits. Today, there is no outside of the digital, there is only during, endurance and infatuation.

Footnotes

- ^ Tim Flannery, Digital Art, JAHM Electronic catalogue: http://jahm.com.au/digital-the-world-of-alternative-worlds/.

- ^ Jean Baudrillard, Simulacra and Simulation, Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 1981, p. 4.

- ^ Artie Vierkant, in “What's Postinternet Got to do with Net Art?” by Michael Connor, 01 November 2013: https://rhizome.org/editorial/2013/nov/01/postinternet/.

- ^ Jean Baudrillard, Simulacra and Simulation, p. 1.

- ^ Richard Grayson, “Talkin’ ‘bout their g-g-g-generation”, Art Monthly UK, Issue 389, September 2015.

- ^ Gordon Monro,

- ^ Tim Flannery, Digital Art, Justin Art House Museum, Electronic catalogue: http://jahm.com.au/digital-the-world-of-alternative-worlds/.