The elevator jolts and the doors slide open to reveal a makeshift gallery space within an office space that looks like it has not been renovated since the 1980s. I have stepped into the provisional Artspace, located on the 7th floor of an office building on Lorne Street in downtown Auckland. This is a temporary measure while the permanent Karangahape Road venue has asbestos removed. While the short-term offsite space is distinctly unfashionable, Artspace Director Misal Adnan Yıldız has boldly presented the current group show The Politics of Sharing: On Collective Wisdom with his characteristic confidence in leading innovative exhibition layouts.

The Politics of Sharing ... is a tripartite show occurring in Auckland, Berlin and Stuttgart; billed as a “co conceived” rather than co-curated exhibition between Yıldız and Elke aus dem Moore, the Head of Visual Arts at ifa (Institut für Auslandsbeziehungen/Institute for international cultural relations). The three exhibitions are introduced as a forum to question the notions of sharing, distributing and resourcing. In particular, the exhibition text explicitly emphasises that the show is inspired by Māori mythology and customs “to challenge a Westernised currency”.

But there is something more compelling taking place here that is not addressed in the exhibition description. This is the ethical challenges artists face when collaborating with others that reveal a less strict polarity between the indigenous and Western paradigms to highlight a more complex tension created by their convergence.

This is particularly evident in the work Waitangi 2 Feb-6 Feb 2017 1000+1300 by Local Time. Not your average art collective, Local Time are comprised of artists, theorists and writers, including Danny Butt, John Bywater, Natalie Robertson, Alex Monteith. Since 2007, they have staged projects, hui and actions in various contexts such as festivals, protests, marae, museums and galleries all the while embodying tikanga Māori hand-in-hand with Western European critical theory into their practices of engagement. Their contribution to this exhibition consists of an extensive body of documented conversations and exchanges that took place at Te Tii Marae in the days leading up to this year’s Waitangi Day celebrations – a national public holiday observing the founding agreement between Māori tribes and the British Crown in 1840.

While documentation will never replace the depth and power of live engagement, it is interesting to consider the humility of Local Time who despite their successful individual careers do not assert their presence but rather chose to listen and support opportunities for exchange. This approach is especially important in regards to addressing the historical and current grievances that surround the Treaty of Waitangi – grievances that stem from the variance of meaning between the English and Māori versions that were signed.

The deep ripple effects of this colonial past, particularly in the suppression of te reo Māori, are addressed in the work Tēnei ao kawa nei, tēnei one kawa, tēnei ao kawa nei by Shannon Te Ao who was invited to participate in the show as part of a relational work by German artist Daniel Maier-Reimer. In this work, Te Ao extended the collaboration by inviting three different people to create Māori translations of the lyrics to This Bitter Earth, a 1960s blues song famously sung by Dinah Washington. The song is a soulful lament of land and its yield as a metaphor for human relations and a distant hope of redemption. “And this bitter earth, what fruit it bears what good is love that no one shares?”. This is a fitting subject for te reo Māori given that land is an important fixture within Māoridom. The relationship between humans and the earth is no more evident than in the word “whenua” which has a double meaning as land and placenta.

Even with my limited knowledge of te reo Māori I can spot a number of differences between the three white on black framed texts such as the use of particles before verbs and nouns and also the variable use of macrons above vowels. This difference encourages scrutiny about the ability to translate or transfer the meaning of one person’s grief into another’s context. Or, alternately, that the effects of historic trauma continue to significantly disrupt the meaning- making competencies of those affected. This range of possible meanings gives the work a real potency despite being such a simple exercise.

An equally modest but powerful abstract gesture is enacted in Maumau taimi / Wasting time in Berlin, a video work by Kalisolaite 'Uhila. The video pictures a stationary black clothed figure seated in a grass field outside the previously disused Nazi-era Tempelhof Ufer now Germany’s largest refugee camp. Despite being shot on a lo-fi handycam the footage is hypnotising – the unmoving black figure conjures an eternal presence from which time flows around. After sustained viewing it is apparent that the footage is caught within a time loop. This subtle video editing meddles with the viewer’s perception and renders the black-clothed figure in an endless stasis. This action adds political disquiet to the notion of wasting time by being outside a complex where 1,300 refugees are housed in overcrowded conditions. As such, 'Uhila stages an empathetic critique of global mobility and the political ideologies that dehumanise people.

Another standout work is Maxa Yoawi: the waters below ascended and, while coming down with the ones descending, fell in love by Gabriel Rossell-Santillán. This dual channel video work features a deer farm and, on a separate screen, a group of indigenous Mexican men visiting a museum storeroom. This group of men are made to wear latex gloves, dust masks and hooded Tyvek suits that fit awkwardly over their traditional dress. As the men consider various cultural artefacts, such as objects made from deer antlers and feathers, a lot of considered discussion unfolds. But since this dialogue is not subtitled into English or German this knowledge remains their own. The artist has provided a short two-page text written in English that goes some way to explain his process and motivations in creating this collaborative work.

Through a diaristic narrative, Rossell-Santillán recounts his early discussion with curator Elke aus dem Moore. As their conversation unfolds it is revealed that the artwork featured is the result of collaborating with members of the Wirrarika community, the first nations people of central Mexico. The work was originally meant to result in an archive and educational resource to maintain traditions, but was derailed due to alleged government corruption. Instead, the community used funds raised by Rossell-Santillán, through the sale of an obsidian rock, to build a deer reserve. The artist’s story ends with him standing at the edge of a forest on a crisp morning imagining the panthers that might be lingering in the nearby shadows awaiting the gift of sacrificial deer. This poignant project reveals the artist’s ability to go with the flow and embrace the adaptive resilience of communities in maintaining their culture and life traditions amid contrary forces.

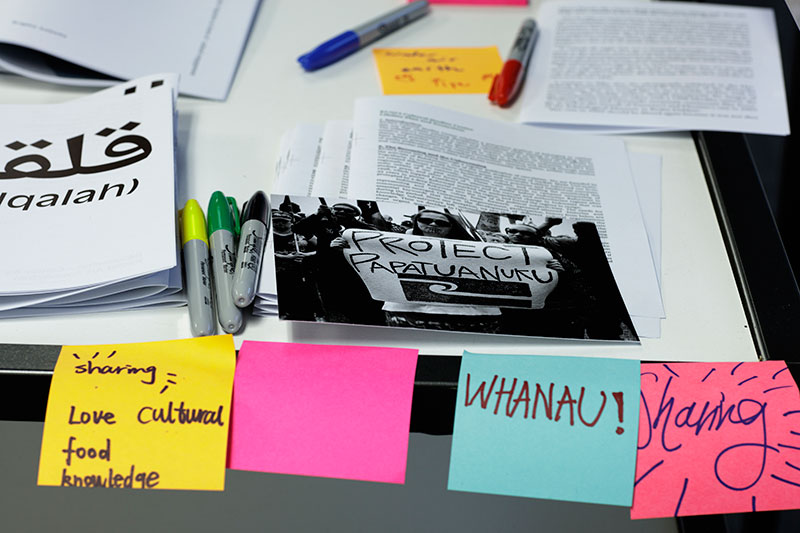

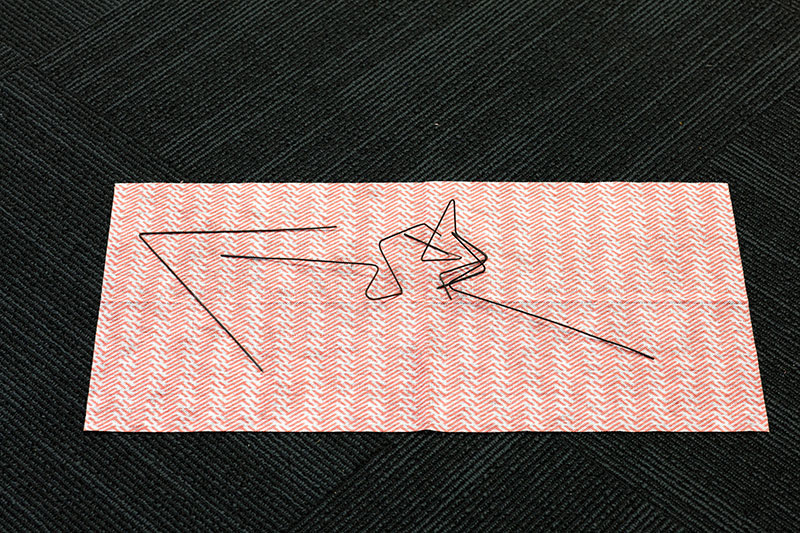

Some of the works in the show suffer from the provisional display structures and patchy lighting, such as Lonnie Hutchinson’s exquisite cut paper works that deserved a space with less distraction to give them the reverence they deserve. Taking more advantage of the ad hoc conditions, Peter Robinson used the opportunity to play by creating numerous Richard Tuttle-like sculptural vignettes of wire and kitchen cloth placed throughout the space. Also embracing the makeshift, KUNCI's reading area that will vex those who bemoan the superficiality of “interactive” post-it note displays. Yet despite this aesthetic quibble, KUNCI have assembled a discerning collection of readings and a glossary unpacking the notion of the commons. AbdouMaliq Simone's essay People as Infrastructure: Intersecting Fragments in Johannesburg is particularly enlightening.

This exhibition has been framed around holistic principles found within Māoridom as an antidote to the individualistic, capitalist and colonial agendas entwined within Western paradigms. Indeed, there is much that our world could benefit from by being more attuned to such baskets of knowledge. The curatorial text glosses over these concepts in an optimistic manner that runs the risk of creating an exotic perspective of indigeneity for the benefit of Pākehā and German audiences. But thankfully the selected artists resist the lightness of the exhibition’s curatorial framing by revealing, through their work, the uncertainties, tensions and struggles that indigenous communities face and the pragmatic necessity to work within and outside of hegemonic institutions to strategically enact change. In terms of artistic practice, there is also an additional dimension present in the show revealing how the artists incorporate slowness, humility, experimentation, reflexivity and tactical approaches to deal with the complications of collaboration and the ethics of representation. These approaches are essential to partaking in and subverting a European dominated artworld that is very much determined by assumptions of what is “contemporary” and what is “art”. The Politics of Sharing is an insightful show that provides the basis for a rich conversation between artists from different ideological and geographic corners of the world.

2016. Photo: Sam Hartnett