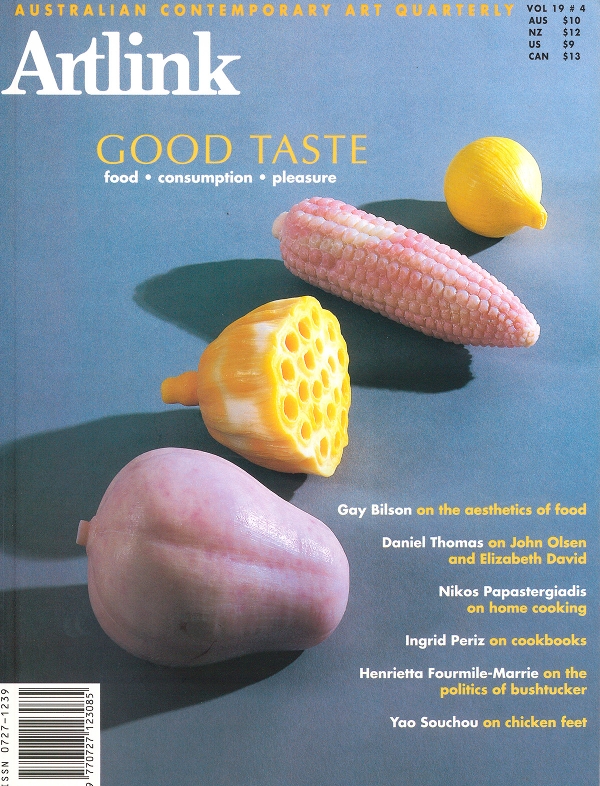

Good Taste: Food, Consumption & Pleasure

Issue 19:4 | December 1999

Guest editor Hannah Fink. There is a current of nausea running through this issue...yet this queasiness has perhaps more to do with a dis-ease with the manner in which we take our pleasures than the creative impulse itself. Food as cultural history, cookbooks, artists as cooks, artists' recipes, being Greek in Australia, artists and restaurants, paintings about food, bush tucker, honey in indigenous art, monument to Irish famine. Reviews

In this issue

Cash Crop: Fiona Hall

Faites Vos Jeux: Aesthetics and Dis/Order in Kennett's Victoria

Explores the idea that basic qualitative aesthetic lifestyle values in Australia are by no means neutral but highly coloured by political judgements. The mood and style of the governance of Victoria can be read as an issue of taste and lifestyle as well as political ability/responsibility.

Tasteless

Editorial for the edition on Food Consumption and Pleasure. Summarises the treats which lie in store for the reader of the issue, linking the disparate approaches of the various writers .

Pictures on Plates

Divided into subheadings 'The Parsley Garnish' 'La Nouvelle Cuisine' 'Transgressions' the author explores the role of food and decoration -- pictures on plates -- in Australian (and wider) cuisine from the 1950s through to the 1990s. Refers to Marinetti's The Futurist Cookbook of 1932. Examines photographs of food and the paradox of indulgence and self denial.

Mediterranean Paradise: artists and the kitchen: David Strachan and John Olsen

Examination of the work of David Strachan and John Olsen from the 1950s in Europe to Australia in the 1980s and the pleasures of painting and food. Linking of painting with the recipes and philosophies of Elizabeth David.

Breadline: Women and Food

Since the advent of 1970s feminism, the joining of women food and art has been about mixing a metaphoric concoction of consciousness raising, community and corporeality. Looks at women's art movement practice in South Australia

Cookbooks

Examines the relationship between food, cookbooks and the art of illustration. Cooking however elaborate is always about the assuaging of hunger but.....Looks at Elizabeth David's 'Italian Food' published in 1954 and illustrated by Renato Guttoso. John Minton had illustrated David's earlier books.

Bush Tucker: Some Food for Thought

Bush tucker (food and medicinal purposes) for indigenous communities is looked at in terms of commercial opportunities with traditional knowledge finding application in contemporary contexts. Examines the role of aboriginal people in scientific research and subsequent commercial exploitation. Also looks at issues of Aboriginal intellectual property.

Honey: It's Meaning in Aboriginal Art

Across the far north of Australia, honey is enshrined at the centre of life's meaning as a nourishing and creative presence in a landscape derived from the Ancestral Beings themselves. Looks at the visual representations of honey for the Dhuwa and Yirritja people. Discusses the creation myths and their contemporary expressions in bark paintings and sculptures.

Nostalgia, Nation and Gobstuff

Linking of food and memory == elements of nostalgia for other times and places. Proust and James Joyce and the role of food in their writing and the centrality of place or locality in food. The 'authentic' and the 'other' have been amalgamated.

Greek as a Souvlaki

Musings on seeds, weeds and the author's mother's cooking. An exploration of Greek food, issues of multiculturalism and history. Touches on genetically modified food and colonisation.

Fast Food: Don't spoil your appetite

Art and its relation to the museum may be seen in terms of the analogy of food passing along the intestinal tract. Looks at exhibitions like EAT 1998. Food is one kind of culture that is always in demand. Why not give the public what it wants. Eating in art galleries may break down the barriers of art as an exclusive kind of experience,

An Gotta Mor: A Sculpture for the Irish Famine

In 1999 The Australian Monument to the Great Irish Famine at Hyde Park Barracks was unveiled. Designed by Hossein and Angelea Valamanesh, it commemorates the arrival in Australia of young women many of whom were orphaned by the great hunger. National competition within the constraints of the Francis Greenway building and historic precincts.

Force-Fed: Food in the Art of Destiny Deacon.

Discusses 'Home Video' made in 1987, 'Welcome to my Koori World' (1992) and 'I don't want to be a Bludger' (1999). Food in these videos is the bearer of sly innuendo, misguided intentions, complicated emotions. In these invented worlds food is either inedible, unnourishing or unavailable or a lurid torrent of junk food.

Homemade: The Rosalind Brodsky Cookery Show

Looks at the CD Rom by Suzanne Treister 'No other symptoms - Time Travelling with Rosalind Brodsky'. There are two cooking segments on the CD. The cooking demonstrations are imbued with historical and cultural pain and prejudice.

My Millennium Dome: Domes Tripe and Teacups in the art of Donna Marcus

Donna Marcus series of Millennium Domes imagine the everyday aesthetic practices of living in houses and with objects in terms inflected by processess of memory, dream and the imagination. Reference to the geodesic domes of Buckminster Fuller organic materials and recycling.

Nariphon: How to eat a bowl of noodles

Examines the series of paintings Nariphon I-III by Phaptawan Suwannakudt which deal with issues of change and consumption, absorption of multicultural practices into dominant cultures -- Prostitution (girl fruit) and survival in Thailand. Her work blurs the distinctions between meditation and revolution (east and west) and between tradition and modernity.

Recipes: Writers and Artists Share their Favourites

Recipes put forward by the artists in this issue for all sorts of delectable and interesting dishes - some real and some not so real. Includes recipes of John Olsen, Daniel Thomas, Anders Ousback, Gay Bilson, Juliana Engberg, Phaptawan Suwannakudt, Kajri Jain, Yao Souchou, Rosalind Brodsky, Anne Graham, Jennifer Isaacs, Gwyn Hanssen Pigott, Nikos, Brigitta Olubas, Freda Freiberg, Hetti Perkins and Destiny Deacon.

Art + Food = Lucio

Review of the book 'The art of food at Lucio's' by Lucio Galletto and Timothy Fisher, introduction by Leo Schofield. Foreword by Robert Hughes Craftsman House 1999 Sydney RRP $65.

Set Menus

Book Review Reel Meals, Set Meals: Food in Film and Theatre by Gaye Poole, Currency Press Sydney 1999 Links the consumption of food with the consumption of culture.

Designing the Hot Potato: Food, Design and Culture

Book Review Food: Design and culture Edited by Claire Catteral London; Lawrence King Publishing in association with Glasgow 1999 Festival Company

Craft and Contemporary Social Ritual: Eating and Drinking

Book Review Craft and contemporary Social Ritual: Eating and Drinking Craft Victoria Melbourne 1999 $35 "Discussion about craft has moved apace and this publication proves it."

Rosalie Gascoigne AM

Obituary for Rosalie Gascoigne AM Born Auckland 25 January 1917 Died Canberra 23 October 1999

John Davis

Obituary for John Davis Born 16 September 1936 Died 17 October 1999

Wladyslaw Dutkiewicz

Obituary Wladyslaw Dutkiewicz Born Lwow Poland 21 February 1918 Died Adelaide 2 October 1999

Antony Hamilton: Mythology of Landscape

Survey exhibition, Art Gallery of South Australia

3 September 7 November 1999

Twenty Five Years and Beyond: Papunya Tula Painting

Curated by Doreen Mellor and Vincent Megaw

Flinders University Art Museum City Gallery, Adelaide

4 September - 17 October 1999

Flinders Art Museum Campus Gallery

6 September - 22 December 1999.

Body of Language: Roseanne Bartley

Craft Victoria

Melbourne

5 28 August 1999

One Sculptural Furniture

Annette Cock, Yvette Dumergue, Kathy Fox

Stairwell Gallery, The Public Office, Melbourne

Messengers from the West

A video-art project by Mayza Hamdan, Joanne Saad and Marian Abboud

Artistic Director: Vahid Vahed

Artspace

30 Sept - 23 October

What John Berger Saw:

Robert Boynes, Susan Fereday, Elizabeth Gertsakis, Dean Golja, Paul Hoban, John Hughes, Tim Johnson, Peter Kennedy, Peter Lyssiotis, Polixeni Papapetrou, Gregory Pryer, Anne Zahalka, Constance Zikos, The exhibition features a collaborative work by John Berger and UK artist John Christie.

Canberra School of Art Gallery

10 September - 6 November 1999

Australian Tour

2000-2001

Remembering Chinese: Gregory Kwok-Keung Leong

University Gallery, Launceston

5 - 27 August 1999

Craft Victoria

30 Sept - 30 Oct

Burnie Regional Art Gallery

13 Dec - 1 Jan

WARP

John Vella, Neil Haddon and Phillip Watkins

Curated by David Hansen

CAST Gallery, North Hobart

9 July - 1 August1999

Robert Juniper

The Art Gallery of Western Australia

11 September - 21 November

Brenda L. Croft, Destiny Deacon & Glen Hughes

Brenda L Croft:In My Father's House

Destiny Deacon:Postcards from Mummy

Glen Hughes:One Family:

Perth Institute of Contemporary Art

12 August - 12 September 1999

The Third Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art

Queensland Art Gallery

9 September - 26 January

History and Memory in the art of Gordon Bennett

Brisbane City Gallery; July 29 - Sept 4, 1999

Ikon Gallery, Birmingham: Nov 20, 1999 - Jan 23 2000

Arnolfini Galleries, Bristol: Jan 29 - March 12, 2000

Henie Onstad Gallery, Oslo: April 9 - June 12, 2000

Artrave