This new look Big Ideas edition of Artlink puts the spotlight on art of scale, scope and visionary capacity. It coincides with Australia’s three major recurrent exhibitions of contemporary visual art: the 8th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art in Brisbane (21 November 2015 – 10 April 2016), the 14th Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art (27 February 15 – May 2016) and the 20th Biennale of Sydney (18 March – 5 June 2016).

Like the planets portentously aligned for a brief period, these events harness the collective resources of many of our cultural institutions and a large pool of artists (mostly) flown in from elsewhere. “Biennales” – for want of a more appropriate collective term – bring with them an expectation of big ideas and provocative themes.

There is great opportunity for artists to do remarkable things in new sites and contexts, as taken up by Robyn Stacey in her deployment of the inverted eye of the camera obscura light box occupying various unique historical venues across Adelaide, for this year’s Biennial, curated by Lisa Slade. Read my interview with Lisa and our review of Stacey’s installations for the Museum of Brisbane exhibition Cloud Land in 2015 in Artlink 36:1 (also online at www.artink.com.au).

As the first cab off the rank, the opening weekend of presentations and performances for the Asia Pacific Triennial (APT8) in late November was an event-full experience, ongoing over the summer. Race, place, practice and politics are as always big on the agenda, as captured in Hetain Patel’s Be Movie 2.0, channelling the return of Barack Obama to Brisbane with his alternate version of the Nobel Prize acceptance speech turned into a demonic corporate take-over (see it available now on YouTube and TV.QAGOMA).

Scene-stealing performances (some of them ignoring institutional protocols on nudity) by Rosanna Raymond and her collaborators for the SaVAge K’lub were another highlight of the APT8 opening exhibition and events program. But, as Raymond’s commanding performances went some way to demonstrate, our institutions have a long way to go, before they are adequate to the task of representing and not just showcasing Pacific and Indigenous perspectives. Among the artists from APT8 reviewed and profiled in this edition, Léuli Eshragi’s interview with Raymond and a number of First Nations curators highlights these concerns.

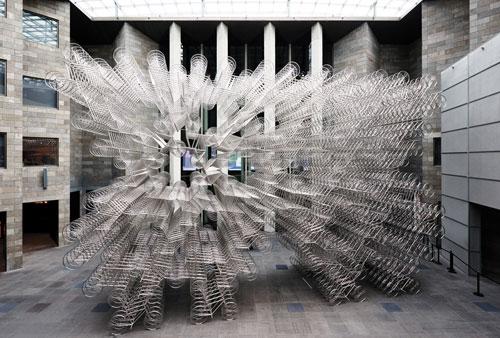

Over the last few months, Stephanie Rosenthal, Director of the Biennale of Sydney, has kept up an impressive schedule of public talks in contemporary art spaces and galleries around the country to build interest in BoS20 opening in March. The international selection of artists rivals even that of the APT8 for its notable diversity along with the expanded range of host venues and sites across the City of Sydney.

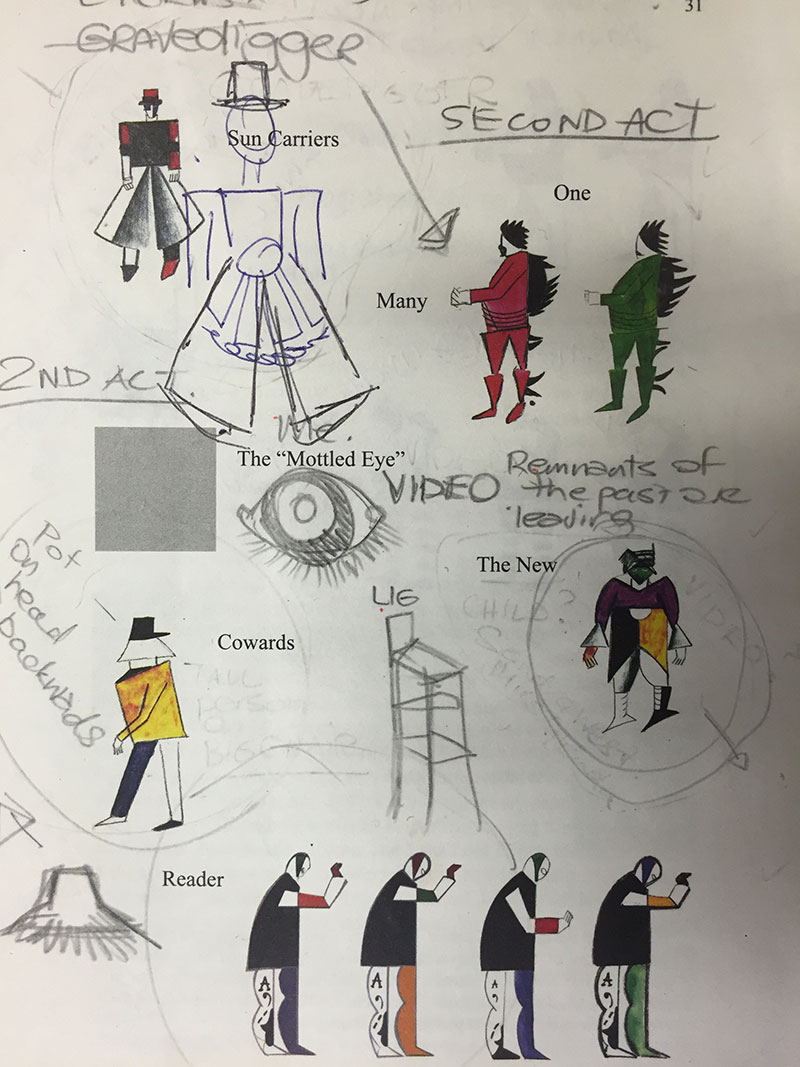

If Adelaide has its Wunderkammer, Sydney has its Gesamtkunstwerk in a new work commissioned for the Biennale of Sydney by Justene Williams working in collaboration with the Sydney Chamber Orchestra in a restaging of the Futurist opera Victory Over The Sun. First performed in St Petersburg in 1913, with music by Mikhail Matiushin, nonsensical text by Alexei Kruchenykh, and stage sets and costumes by Kazimir Malevich, Williams has set herself a notable challenge. As the mistress of Zaum, Psycho-Pomp, and her own brand of visually and acoustically dynamic performances, this is her biggest production yet, employing a team of sewers and makers to realise her remarkably Kazimir-like designs.

Not everyone is of course as enthusiastic as I am about institutionally-driven big programming. In this issue, Ian Milliss takes to task the rumblings of discontent that surfaced around the time of the last Biennale of Sydney, suggesting we go so far as to “boycott all biennales” to drive new agendas for art and society now. And in a thoughtful essay on artists working in war zones, Darren Jorgensen draws attention to the remarkable courage of artist George Gittoes, who was never my favorite painter, but has my unbounded admiration for taking on the Taliban to make movies with the street kids of Jalalabad.

One big thank you to all the writers and creative producers who have contributed to this edition, a full list of whom are appropriately credited across the pages. And, a further special thank you to Marita Leuver and team of Leuver Design and Isaac Foreman, Triplezero, for their big contributions to the development of our sharp new magazine and online edition.