Sand-covered children swing gleefully from a brilliant orange sculpture. My concern for the preservation of Steve Tepper's citrus-hued work is dispelled by signage that encourages climbing. Peering through writhing limbs, I really appreciate Tepper’s manipulation of thick steel pipe into this callisthenic marvel titled Bob, and its playful allusion to bobbing life preservers. I’m less convinced by the sculpture’s orange-painted graft to a concrete base.

Nearby, Rhett Jones’ Gallery Bench mimics a modernist expanse of full-grain black leather. Positioned on the sandy terrace outside Kidogo Arthouse, Jones’ institutional creature comfort constructed of timber and metal is wonderfully at odds with the beach setting, yet leaves many viewers failing to recognise the imposter.

Artist, philanthropist, and long-standing TAFE lecturer in sculpture, Tony Jones (OAM), and Joanna Robertson, Director of Fremantle’s Kidogo Arthouse at Bather’s Beach instigated Sculpture@Bathers. Unlike the concurrent international Sculpture by the Sea (SXS) Cottesloe exhibition now in its ninth year, Sculpture@Bathers is touted as an inaugural "homegrown show" featuring only artists from Western Australia. Another point of difference is that Kidogo Arthouse also features artists who do not create outdoor sculpture; hence to see their work in a survey-style exhibition is unique. Like SXS, Sculpture@Bathers offers indoor and outdoor works for sale. The number of red dots dispersed across sixty-one works, and the telephone inquiries I overheard from callers seeking to purchase works already sold, suggests sales at Sculpture@Bathers are comparatively brisk.

It is wonderful to experience aquatic themed works in a beachside exhibition. Renowned for her kiln-cast pâte de verre sculptures with a nostalgic twist, Denise Pepper’s Glamour Splash features four glass bathing caps with perky floral motifs and latex-embossed, candy-coloured patterns. In contrast, Anne Neil’s I dream, a delicate stacking of miniature cast merino sheep alternating with shipping containers, comments on the local export of livestock. Linde Ivimey’s Luscinus, a rabbit-eared figure painstakingly covered in Ivimey’s trademark webbing of finely stitched fowl and fish vertebrae, for this occasion dons inflatable plastic armbands. These seem somewhat incongruous in relation to her stock materials and handcrafted oeuvre. Symphony of the Sea, Pam Langdon’s dense ceiling-to-floor cascade of cassette tape hearkens a massive glossy garden of swaying seaweed and the haunting calls of whales whose carcasses were once dragged up onto this shore for processing.

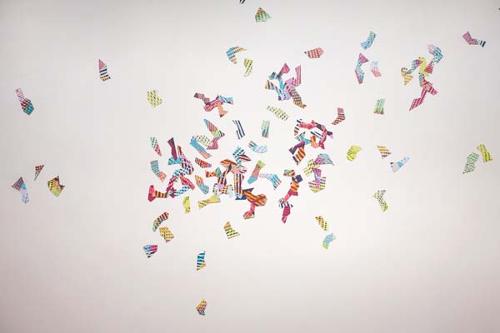

The inner sanctum of Kidogo Arthouse is reached by climbing through a rough hole in the old limestone wall and features primarily illuminated works. Brainstorm, a mesmerizing kinetic work by Jennie Nayton, consists of hundreds of paper planes flying in a tight floor-to-ceiling vortex. This work, together with David Kenworthy’s colourful, low-hung illuminated word work, is clearly appealing to poorly supervised children.

On the beach, as though having emerged from a swim only seconds ago, two fine-boned, spirited horses shake off water. Constructed of old corrugated and painted pressed tin, Claire Bailey’s Horse Moves demonstrates exquisite equestrian details, especially in the poses and finely welded wind-tossed manes and tails. Another sculpture that responds well to the beach setting is Our Common Condition, Russell Sheridan’s large concrete and fibreglass woman wearing a frock and dress shoes sitting on the edge of the boardwalk. She’s roughly textured, refreshingly not beautiful, and half-heartedly playing with a dog that sits peculiarly upright in the sand below with hind legs stretched out in front.

Nearby, Maid With My Own Hands by Judith Forrest is a cast bronze girl. Wistfully facing the ocean, her face is sensitively modelled compared to the rest of her. On her shoulderblades she dons oversized, crudely formed, older hands suggesting wings. These larger-than-life hands suggest capable older women who have the knowledge to impart many resourceful skills for hand-making objects.

Simon Gilby’s figure, located in Whaler’s Tunnel beneath Fremantle’s historic Round House Gaol, haunts me. Where punishment was meted out, Gilby’s lattice-welded work titled Remains is like a shell of a body. Hanging on thick chain from the static figure’s arms are solid, black-clenched fists.

A highlight for many was Tim Burns and Bruce Abbott’s Fire Delivery, entailing restorative burning of grass trees uprooted by urban expansion. Overall I enjoyed exploring the diversity of works on show. I also applaud the efforts needed to pull off an exhibition of this scale.