In Alfred Hitchcock's surrealist film The Trouble with Harry (1955)[1], a man from a small country town is mysteriously found dead in a field one morning. In the ensuing chaos the townspeople’s reactions range from guilt, remorse and then blame as the people who knew him best question their own possible involvement in events that might have caused "Harry’s" untimely death. In the story that takes place there are multiple versions and accounts of the man’s character and divergent accounts of very different histories with very different people over many years.

I was reminded of Hitchcock’s film when attending the funeral for the artist Harry J. Wedge in November last year. This surreal plot is a fitting introduction to the telling of the story of the life and work of Harry James Wedge. Harry’s work as an artist could easily best be described as polarising; many loved it, many hated it; some liked it but could not understand why others would love it so much; and some celebrated the fact that others hated it so much.

Harry’s artistic career remained an enigma to those closest to him throughout his life. His work is an exemplary case of an Australian outsider art - though not in the conventional definition.

Self-Taught and Outsider Art is art produced by people somehow excluded from 'the art game’ – not by choice, but by circumstance.[2] Harry was often baffled at the serious critical reaction that would accompany his exhibitions. Harry was known as ‘Big H’ by those in his home community of Cowra in the central west of New South Wales and it is a fair character assessment to say that he was not shy of a drink or a smoke and a gamble.

I met him very late in his career when he was rarely producing new work. He was instead relying on a catalogue of around 50 unsold works that would often be acquired by astute collectors visiting Boomalli, Aboriginal Arts Co-operative in Leichhardt in inner Sydney. I often had the task of ringing him to tell him that he had made another sale and more often than not this news would be followed up with a phone call the following day, and the day after – asking if he had made any other sales, as his overly generous nature and reliance on the assistance of his friends would often leave him broke again very quickly.

I never begrudged Harry his tendency to ‘humbug’[3] – there was no shame in it really. I could well understand why he would do it but at the same time I also understood that it could be very off-putting for anyone not accustomed to it. Aboriginal people were ‘outsiders’ by government design well into the late 20th century and in the short time that I knew him Harry’s health and welfare circumstances grew gradually worse. I knew some who thought he was crazy for not just pushing lazy art through the system – “Why don’t you just do some more paintings?” – but any serious artist will tell you that it is not as simple as that. Harry seemed to understand what was at stake: that for an artist to flood the market with lazy or mass-produced work can risk and undermine their long-term artistic viability. Harry seemed to know how the art world worked better than most and had been around long enough to know when to hold and when to fold.

Harry grew up in Cowra – a place with its own fascinatingly contradictory histories relating to its displacement of the local Aboriginal community – the Wiradjuri, but also popularly known in Australian history as being the location of a Japanese internment camp in World War II and the infamous Cowra breakout depicted in the 1984 mini-series directed by Phillip Noyce. It is interesting that Noyce also directed the 1977 film Backroads[4] which begins its narrative trajectory on the Brewarrina mission known as ‘Dodge City’[5] – another filmic parallel to the beginnings of Harry’s artistic journey from a regional town in New South Wales to the city and the bypasses and backroads that shaped his life’s journey.

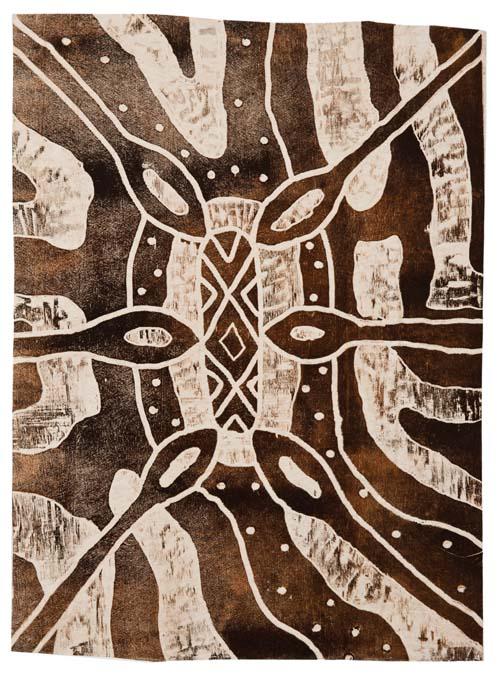

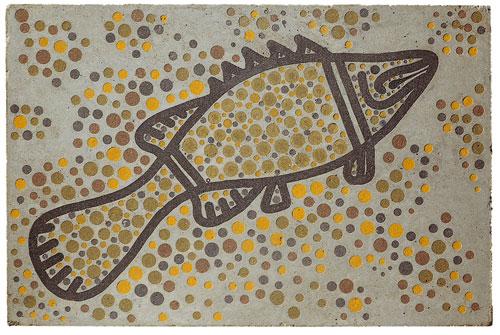

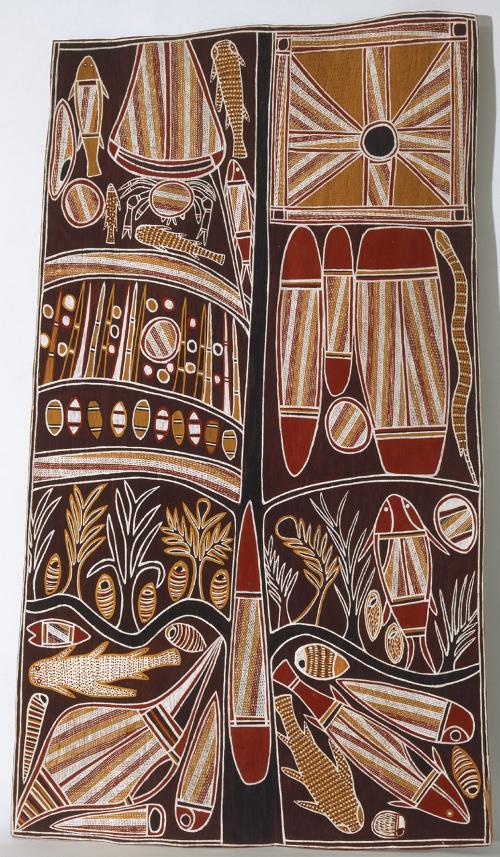

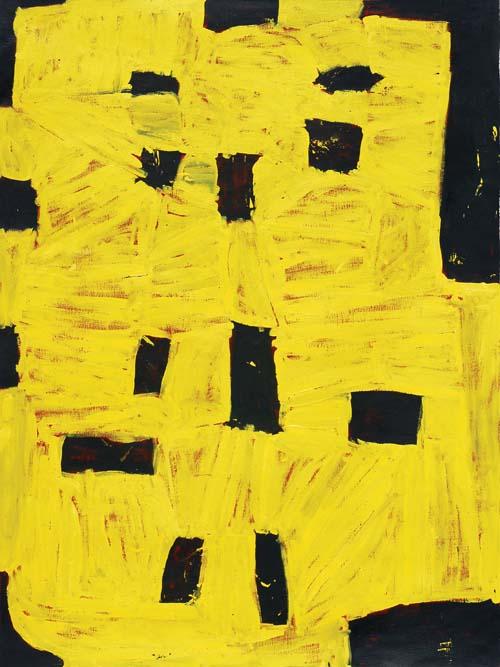

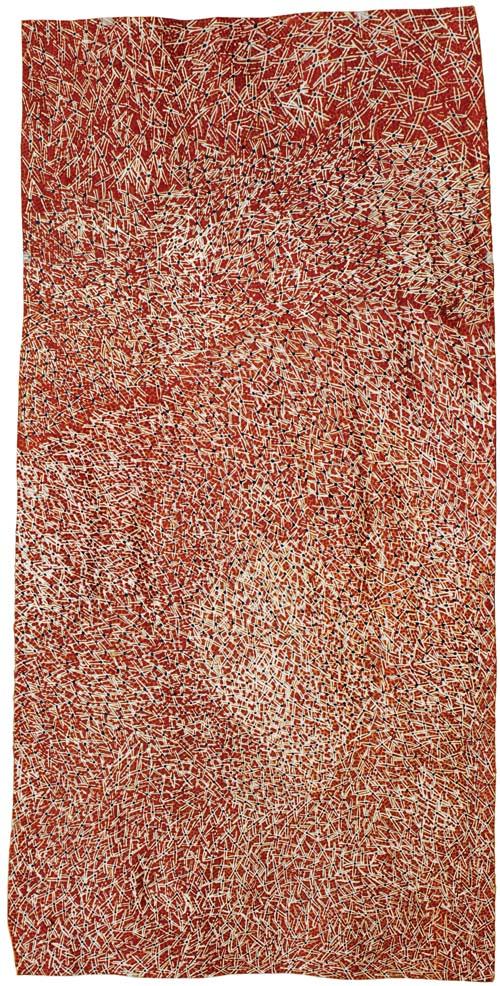

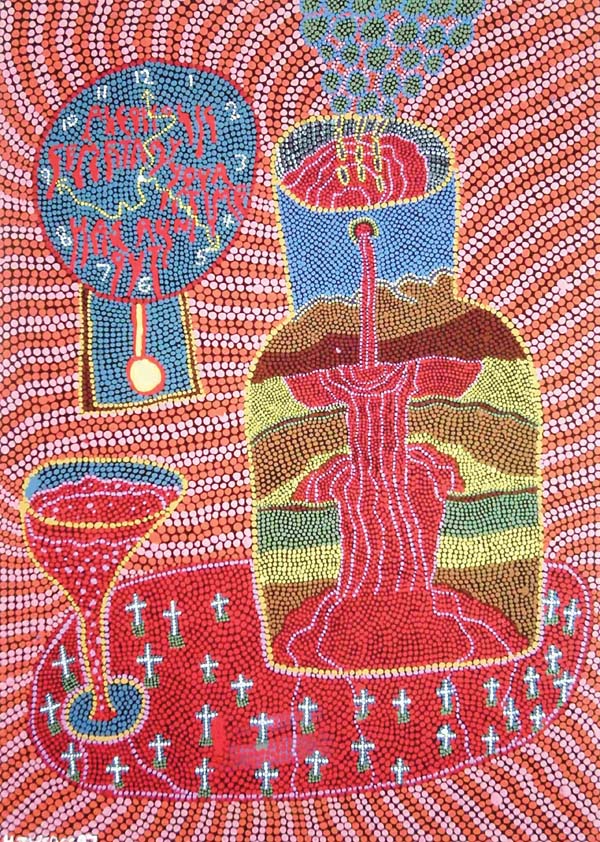

In 2012 the urban Aboriginal art movement lost two of its most successful proponents in Ian W. Abdulla and Harry J. Wedge. Harry and Ian forged personal expressive visions that are instantly recognisable in the oversupply that has come to define so much government-funded remote art centre ‘traditional’ Aboriginal art today. Harry and Ian first exhibited together at Boomalli in 1991 and both came to define a first-person, naïve style of storytelling and painting that overtly displays a unique perspective on their personal life experiences.

They painted with wholesale-bought acrylic paint, large bottles of primary colors that were often poorly blended together. Most artists these days have not touched these types of paint since primary school but for emerging Aboriginal artists from south-eastern Australia their work was largely defined by an unschooled, deliberate and willful ignorance of ‘the rules’ of the art world and this is what made their work so shocking, vibrant and visually refreshing.

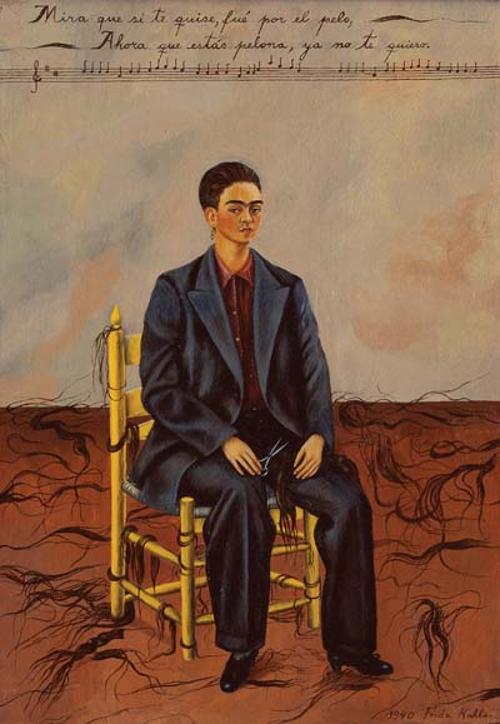

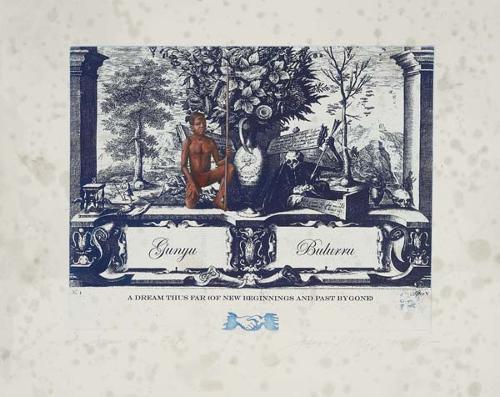

The story of Harry’s artistic career is intertwined with the growing sense of identity politics that from the 1970s onwards transformed modern Australian society profoundly. In an era dominated by the anthropological and ethnographically sanctioned ‘traditional’ art of the remote art centres, artists such as Harry J. Wedge, Robert Campbell Junior and Ian W. Abdulla navigated their way into the Australian contemporary art world to great acclaim through using a fresh artistic approach that rejected the conformity of many other Australian schools of art.

The unschooled ‘neo-expressionist’ work of urban Aboriginal artists was far more in tune with the international aesthetics of contemporary international painters of that era such as Jean-Michel Basquiat, Sandro Chia or Phillip Guston where formal painterly qualities are secondary to the primacy of the subject and its expressive emotional qualities. Many significant Australian artists of that time such as Davida Allen or Jenny Watson also worked (and still work) in this first person diacritic narrative.

Harry’s work hung proudly in many of the best Australian art survey shows of the 1990s. It was through the dedicated work of Aboriginal curators Hetti Perkins and Brenda L Croft that Harry reached national exposure in exhibitions such as Australian Perspecta 1993, the 2002 Biennale of Sydney and the first Indigenous Art Triennial, Culture Warriors in 2007.

The success of artists such as Harry and others from this era has provided the groundwork and inspired Aboriginal artists from across many regions of Australia such as Jimmy Pike and Ginger Riley and more recently artists such as Trevor Turbo Brown, Billy Benn and Elaine Russell.

During the 1990s – the most successful decade of his relatively short career – Harry would have conservatively sold a few hundred thousand dollars worth of paintings. When Harry passed away in September last year he had little to show for it – in the weeks before his passing he had been the recipient of clothing from the Cowra St Vincent De Paul Society and was on a managed income arrangement with the nursing home that provided comfort for him in his last days.[6]

Harry’s story is a sad example of the social spaces that Aboriginal people moved through in the late 20th century. The drastic social changes that affected Aboriginal people and communities in south-eastern Australia from the late 1960s onwards deserve closer historical scrutiny if these times are to be explained to future generations of Aboriginal people with any sense of authenticity.

In 1984 the historian Peter Read published Down there with me on the Cowra mission, a fascinating account of life on Erambie mission near Cowra told through the oral histories of around 40 people who grew up on the mission. In the past, historical accounts of mission life relied on the written accounts – old style historical narratives produced by self-serving mission managers and held by government archives as a biased historical proof of the experience that favoured the government’s version of events over that of the people.

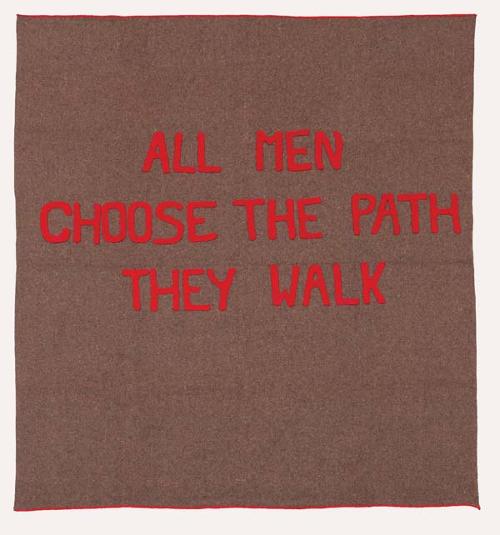

One story that recurs in many of the oral histories is the radical changes in the social life of the mission in the early 1970s when the era of mission managers ended and missions and reserves started being managed by outsiders. On Australian missions and reserves the role of the father was replaced by that of the manager. This meant that over several generations the role of the father in the family became gradually eroded and disparaged to the point where it has become almost a cliché to describe the experiences of Aboriginal men as a “crisis of masculinity”.

Much was promised but little had changed in the period between the 1967 referendum campaign and the 1972 Tent Embassy protests. Employment opportunities were scarce, access to a quality education was prohibitively expensive and culturally respectful health services were nonexistent.

The success stories of the self-determination movement were the Aboriginal-owned and operated medical, legal and education services that were formed at this time. A sense of agency and self-determination led many Aboriginal people to leave their small town rural communities to move to the urban centres, where these community services had been set up. Harry was part of this internal diaspora and described in his artworks the feeling of helplessness associated with the lack of employment and the social isolation. A constant was his belief in the Wiradjuri spirit and the sense of identity and purpose that this gave him.

The late 1970s until the late 1980s were particularly formative in Harry’s life. In Down with me on the Cowra mission Harry described coming to Sydney in 1976 after a short time spent in a juvenile detention facility and that he was targeted by police seeking to boost their arrest rate.[7] By 1991 Harry was in his mid-thirties and the prospect of becoming a professional artist would likely have been the furthest thing from his mind as he absorbed the growing political consciousness that formed in opposition to the Bicentennial ‘celebrations’. It had many historically significant Aboriginal cultural precedents centred in the inner city of Sydney.

Dr Gaynor Macdonald is an anthropologist and the author of the most definitive academic work on Harry’s artistic career.[8] She recorded the following in an interview with Harry in 2004:

I wasn’t interested in painting at first, I was interested in photography. When you start at Eora you do camera work, painting and screen printing. Then you had Maths and English as well. Then after six months you have to do the Maths and English but you can pick out a course that you want to do. So I picked out mine and there was only Drama and Painting. And I said, there’s no use in taking drama ‘cos I can’t bloody read, so I did painting...

Then one day these figures came up. When I looked at it I thought, this is kid’s work, nobody would buy this shit. I thought my work wasn’t that crash hot. Then in 1989, there was the exhibition at the Eora Centre and I think I had about 13 paintings. People came to price our work. This teacher came and said to me, “They’re goin’ to keep an eye on you” and I said, “Who?” … The people pricing, they think your work is good. I just stood and looked. They ended up selling 12 –there was only one left. I just looked and thought, “These people are crazy.”[9]

In MacDonald’s essay the “soft knife” is a descriptive term that refers to the process of deliberate under-resourcing of the Indigenous self-determination movements in Australia, the United States and Canada. It is a process that disempowers communities when they are challenged with the bureaucratic processes of a dominant empirical society, the “soft knife” is a process that indirectly shifts the blame of responsibility from the perpetrator to the victim and is often the cause of what many have described as “lateral violence”.

One of the most drastic social changes was the right to purchase alcohol that had been highly regulated and arbitrarily used to punish and control Aboriginal people up until 1967. Harry has unflinchingly documented his personal battles with the ‘”demon grog” as he described it, in his work. It was under the influence of alcohol that Harry committed petty crimes as a teenager for which he was placed in juvenile detention. In many ways the problems of young Aboriginal men and alcohol abuse become symbolic of the modern Aboriginal situation – problems of responsibility and leadership.

Recently when I was speaking to fellow artist Gordon Syron he recalled how he first met Harry teaching prisoners at Long Bay Jail in Sydney in the 1980s. Later, he bumped into him at an exhibition in the mid 90s: “I said what are you doing at this fancy art gallery?” Harry replied cheekily “what are you doing here – that’s my bloody work up on the wall!”

As it turns out the death of “Harry” in the 1955 Hitchcock film is underwhelming. It is explained by entirely natural causes and the townsfolk who rushed to condemn others and explicate themselves from the imagined circumstances are left exposed for the vindictive and nasty people that they have always been. I think this is a perfectly apt analogy with some in the wider Aboriginal arts community who never knew the man or his art but are quick to condemn his work as inconsequential in recent years.

In the long run Harry’s artistic legacy is a manuscript of the life of a proud Aboriginal man who lived through the highs and lows of one of the most significant moments of change in modern Aboriginal history.

Footnotes

- ^ 1955 ‘the trouble with harry’ www.youtube.com/watch?v=F3eWgbVvqNYwww.guardian.co.uk/film/2012/jul/02/trouble-with-harry-alfred-hitchcock

- ^ Self-taught and Outsider Art Research Collection (STOARC)sydney.edu.au/sca/research/projects/stoarc.shtml

- ^ en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Australian_Aboriginal_English#Humbug

- ^ Backroads aso.gov.au/titles/short-features/backroads/

- ^ Dodge City, Brewarrina http://www.dodgecitynsw.com/

- ^ Personal correspondence Jan Harper, Harry’s personal carer at Weerona Nursing home, Cowra.

- ^ Peter Read (ed) Down there with me on the Cowra Mission : an oral history of Erambie Aboriginal Reserve, Cowra, New South Wales , Pergamon Press, Sydney, 1984, pp 39 – 40.

- ^ Gaynor Macdonald “painting the soft knife” onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1525/var.2005.21.1-2.98/abstract

- ^ Gaynor Macdonald ‘Encountering Harry as “Artist” ’ p.4 “painting the soft knife” onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1525/var.2005.21.1-2.98/abstract