Twenty years ago, when the eagerly awaited first Asia-Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art opened in Brisbane, we in Australia liked to think we represented the cutting edge of contemporary art in the region. There may have been just a hint of smug condescension toward the quaint village materials that filled the Queensland Art Gallery - things like straw, wood, bamboo, pottery, incense and banana leaves. We also felt rather self-righteous about showing solidarity with our oppressed Indonesian neighbours by supporting their courageously political art. Best of all, we’d noticed that they actually had contemporary art in Asia. These days we’re struggling to get them to notice us.

The APT has been an important gauge of shifting cultural balance. The early exhibitions reflected an Australian view of Asia as an exotic tourist destination. Now Chinese tourists come here, but not to look at our art. The spectacular rise of Asian tiger economies has been illustrated by huge, ambitious APT installations by artists from those countries who have a far stronger following in London, Paris and New York than any Australian. There now seems to be an even greater possibility of Australia fulfilling Singapore Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew’s prediction that we would become the poor white trash of Asia than there was when he made that comment in 1980. We’re already living on Chinese money, and what’s going to happen when the iron ore and coal run out?

The APT is still the most comprehensive and authoritative survey of new Asian and Pacific art, but it’s tempting to wonder if one of these days something bigger and better will be produced in Shanghai. Our strenuous early efforts to be seen as part of Asia have been somewhat diluted in the age of information technology by the fact that everywhere is now part of everywhere else. Twenty years ago we really did have a more sophisticated and international contemporary art scene here than existed in neighbouring countries. That’s no longer true, and Brisbane’s exhibition has evolved to match our changing place in the world.

This time, the Pacific cultures seem to have a more emphatic presence than in past APTs. When the Queensland Art Gallery inaugurated the Triennial, it was partly an antidote to the prevailing neglect of contemporary Asian artists. Now they don’t need any help from us, thank you, and it is the turn of the somewhat neglected Pacific artists to get the Triennial treatment.

During the past 20 years there’s been occasional grumbling that their neglect was most conspicuous in the APT, which despite the claims implied in its title, was far more Asian than Pacific. This was never an entirely fair comment because although these island nations occupy about half the surface of the planet, their populations are tiny compared to Asian nations. Despite their small size, the APT has devoted some meticulously researched and spectacular installations to them over the years.

Equally contentious is the predilection for huge show-stopping installations that acknowledge the contemporary role of the museum in providing entertainment for the masses, and may have been in danger of becoming the Gallery’s house style. This time the cavernous Water Mall of the Queensland Art Gallery is filled, as is now customary for each APT, with an immense work by a Chinese artist. Huang Yong Ping’s Ressort is a 53-metre long metal snake skeleton, which on that colossal scale is automatically suggestive of a dragon. This daunting and magnificent object is the dominant image of the exhibition and a fitting emblem of the power of China.

Nevertheless the current APT is the strongest-ever declaration that Australia is a Pacific island nation. Overall there are fewer extravagant spectacles this time and there’s a quiet, rather refreshing modesty about the whole show. At times it recalls the quaint village atmosphere that prevailed in the first APT and distinguished it from international surveys elsewhere.

A close working relationship with artists’ communities has also, from the beginning, distinguished the APT from the fly-in-fly-out curatorial methodology of many other international surveys. Curators worked for over a year with artists to create the PNG project. A huge Melanesian work is the first thing you see when entering the Gallery of Modern Art (the exhibition spans both buildings, now identified collectively by the acronym QAGOMA). Artists from the Abelam and Kwoma cultures in Papua New Guinea were commissioned to produce full-scale excerpts from their monumental painted architecture. There are sculptures and artefacts from a comprehensive range of PNG peoples.

It took Australia years to realise that China and Japan were not the Far East, but the Near North. The APT has now given an even more realistic view, redefining the Near North to mean New Guinea. Most of its contemporary art looks ethnographically traditional. As a result there is a prevailing impression when moving through many parts of APT7 that you’ve strayed into an ethnographic museum. Sensibly, the Triennial is too expansive to have a theme, but this sense of being something other than an art exhibition is a pervasive keynote.

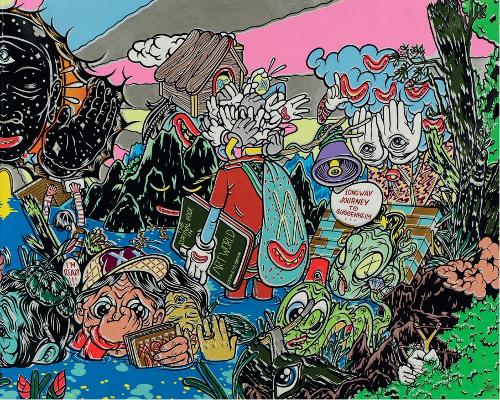

QAGOMA is rightly praised for elegant exhibition design and installation, but this exhibition has the cheerfully jumbled look of the old-fashioned type of museum that threw everything in together. A less aetheticised display makes sense in this case because of the nature of the objects. Some of the biggest works, for example the rambling piece by Japanese collective Paramodel and Australian Richard Molloy’s Big Yellow environmental construction, have a scruffy, scrappy character. The super-scaled skeletal string bags made of scrap metal by Wiradjuri artist Lorraine Connelly-Northey are among the most memorable works in the exhibition.

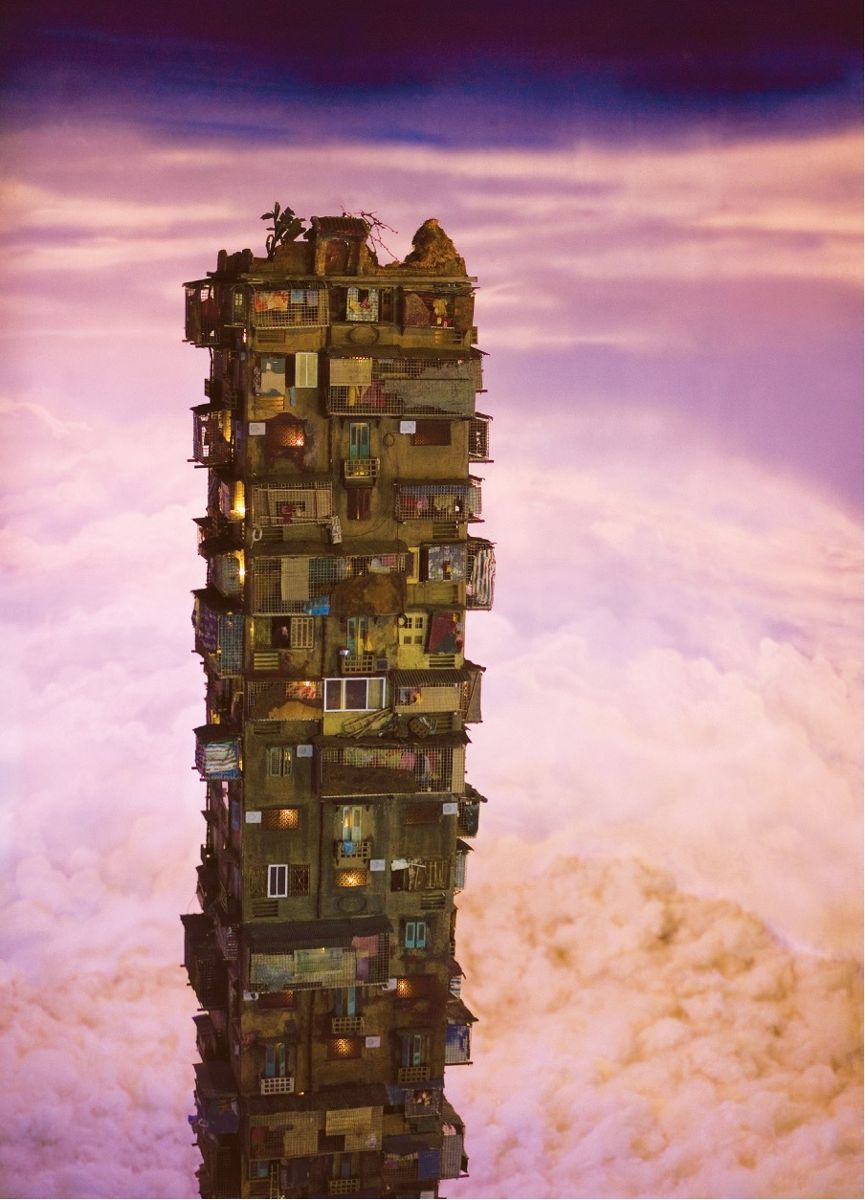

Some exhibits could easily fit into a non art museum. Vietnamese artist Nguyen Manh Hung’s beautiful and intensely poignant Living together in paradise, a sky tower of minuscule slum tenements, is a classic museum diorama complete with illuminated backdrop and cotton wool clouds. At the other end of the suaveness scale is Japanese artist Takahiro Iwasaki’s Reflection Model (Perfect Bliss), an exquisitely detailed cypress carving of an 11th century Kyoto pavilion perfectly mirrored in its own carved reflection. Without its dream-like inverted double, this model would be at home in a museum of architecture. There are also works that could be described as mini museums in their own right. The obvious example of this is Indian artist Atul Dodiya’s Somersault in sandalwood sky, a collection of vitrines filled with paintings and found objects.

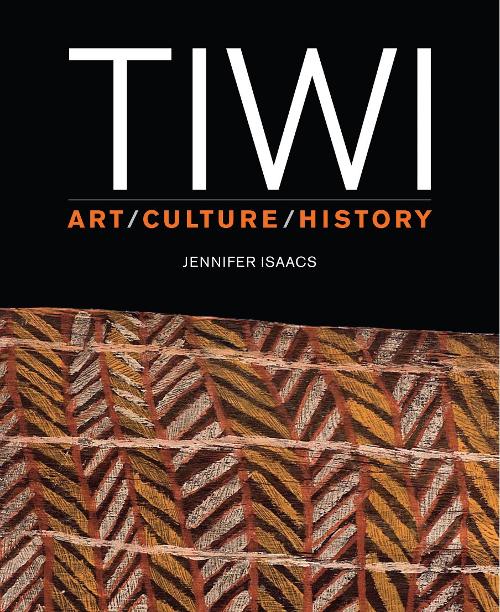

There are, as always, slightly incongruous examples of impressive conventional painting scattered through all this. The sumptuous, velvety surfaces of the big canvases painted in traditional ochres by Tiwi artist Timothy Cook glow against the charcoal coloured walls of their dedicated space, a sensitively conceived place of contemplation. Not all the painters are equally well-served by the hang. The delicate magic realist paintings by Japanese artist Tomoko Kashiki have a lot to compete with on either side. New Zealand artist Graham Fletcher’s paintings of Oceanic artefacts in suburban domestic interiors look exceptionally comfortable in this context. They contain in microcosm the cultural mashup burgeoning all around them.