A social realist in Adelaide

The story of social realist aspirations in art in Australia is often covered up by stories of art as a pursuit of privilege and riches. Success is measured in acquisitions and prizes. Yet success for a social realist is about being able to communicate and to make biting comments on society. In art history socialist realism is associated with paintings of crowds of ruddy-cheeked Chinese peasants bringing in huge harvests and sculptures of strongly muscled Soviet mothers and soldiers bearing children and saving the world. That is another story - state-dictated socialist realist art rather than social realism. Social realism is incisive satire not false facades.

Lidia Groblicka trained at the Academy of Fine Arts in Kraków, Poland at a time when Soviet style socialist realism was being taught. But as she says in the filmed interview on show "The Poles are disobedient people".

Printmaking is the ideal democratic art, it creates multiples and its technical aspects enforce limitations that can make its messages forceful and clear. In the exhibition Lidia Groblicka: black + white, an exhibition of prints curated soon after the artist's death by the AGSA’s Julie Robinson and Elspeth Pitt in 2012, the early works show Groblicka clearly looking at the paintings of Vincent van Gogh and his grim depictions of the miners of the Borinage. Born in 1933 Groblicka’s own life was shaped by World War II and she came to Australia in 1965 as the outcome of a compromise with her husband when they were living in London. He wanted to go to America while she wished to return to Poland. She did not regret living in Australia as she loved trees and bushwalking but missed European architecture, the Polish language and countryside. One of her first works made in Adelaide For the individualist only (1969) responded to the conformity of the suburbs by showing rows of identical houses and their electric poles. It belongs to the genre of art and writing by displaced migrants coming to terms with the apparent emptiness of Australia. Many stories of discrimination also appear in this genre. Groblicka’s work Odd flower out (1992) shows 'the different one’ being crucified.

In the interview with Groblicka recorded by the Adelaide Art Society in 1996 and playing during the exhibition, she says that she wants her work to “be understood by children and even the housewives”. Groblicka’s work makes strong commentary on life, on society, on environmental destruction. It is a dark vision constantly kicking against authority and capitalism. Money is represented as evil. Soul of the corporation (2008) depicts a cash-bloated figure. One tree hill reserve (2006) shows a sole tree surrounded by roads and arrows going nowhere. Beneath the tree a bird has collapsed. The whole life of Mr Bug (1996) cheerfully shows the short and futile path between birth and death.

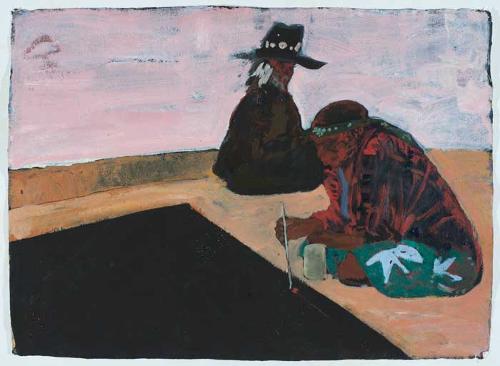

I often saw Groblicka’s work in exhibitions at the Royal South Australian Society of Arts (RSASA) where her work stood out in its political and graphic force. The Art Gallery of South Australia exhibition shows archival material of Groblicka cutting and printing her woodblocks. We see her printing in bare feet, cutting a woodblock while sitting on the ground cross-legged balancing it on a board across her knees with her shoes beside her and our eyes are drawn to the folk art embroidery repeat pattern of lions on the sofa cushion behind her. The sense of great honesty and purpose that is conveyed in the work is present in the person.

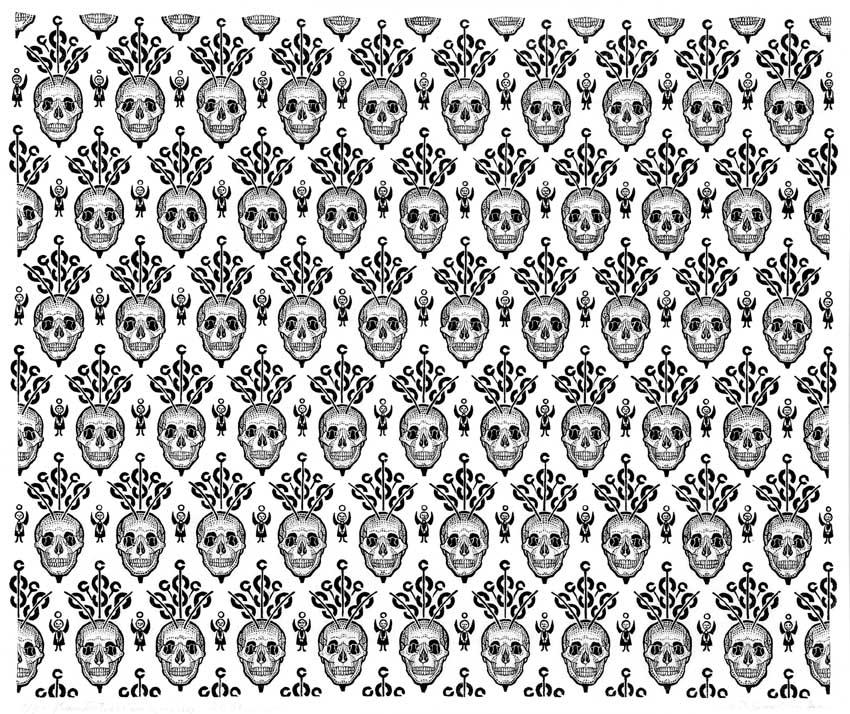

Groblicka’s prints possess intense precision. The print from which an amazing wallpaper has been made especially for the exhibition shows rows and rows of skulls from which dollar signs sprout and next to which tiny smiling angels stand. This repeat pattern is both relentless and mysterious. Its title is Plantation in Spring (2001). Being neither a child nor a housewife I don’t quite get it, or maybe I don’t want to get it. A local printmaker recalls seeing Groblicka demonstrate her printing technique, handprinting on thin paper with a bone held in her palm as a printing tool. Groblicka’s work is certainly close to the bone.