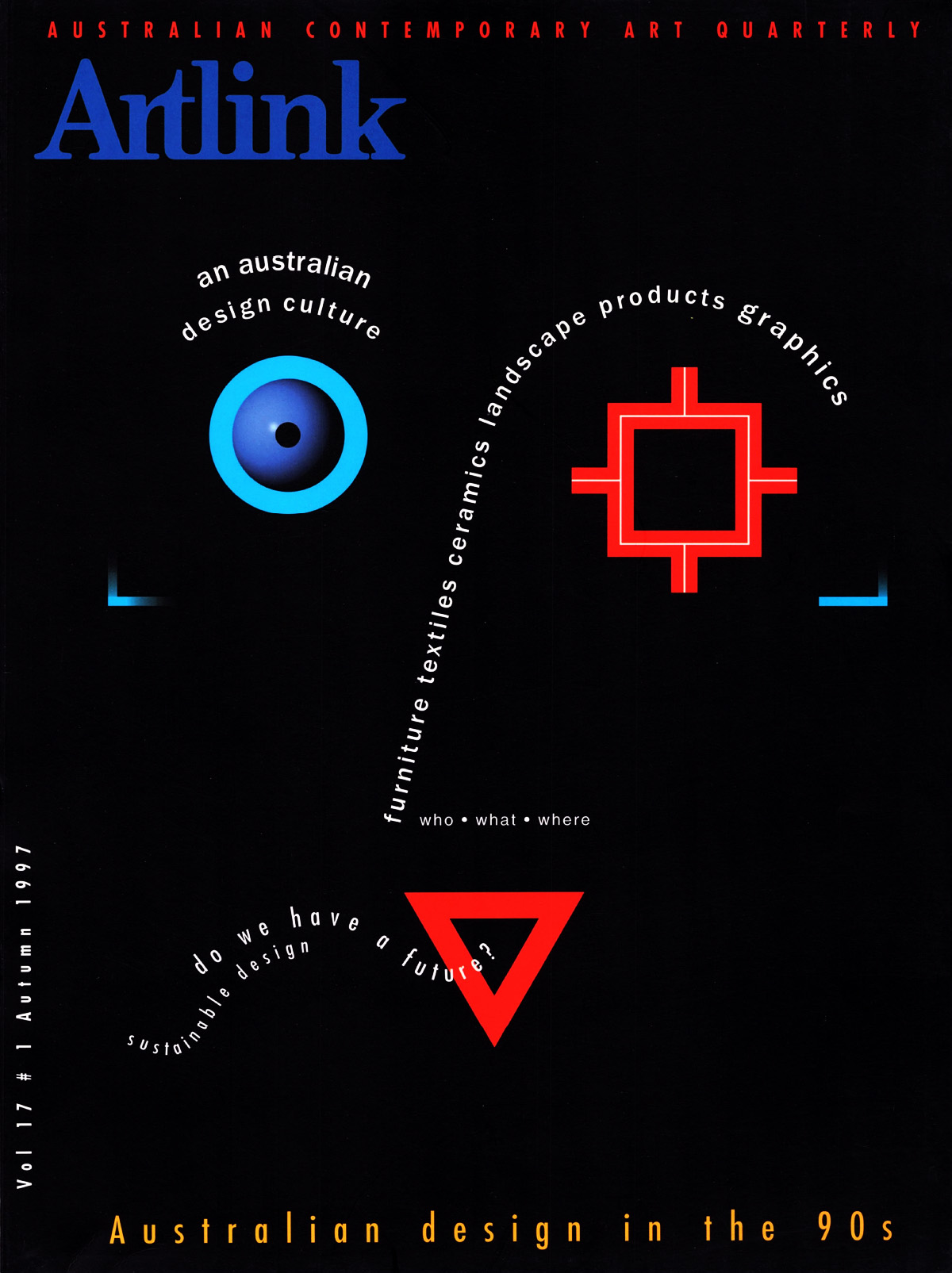

Australian Design

Issue 17:1 | March 1997

Examines the issues of art and design and looks at the practice within Australia in metal, furniture, ceramics, textiles, publishing, graphics landscape products etc. Do we have a sustainable future? Is there an Australian Design culture? Looks at courses which are available through different institutions. Reviews

In this issue

The & of Art & Design

The New Ecodesign: Sceptics Beware!

Whilst on a global scale Australia still dawdles on ecodesign, pockets of cutting-edge research and design are moving ahead with international recognition. Overview of events. In 1991 RMIT in Melbourne hosted the EcoDesign 1 Conference 1989-1992 Designers for the Planet, Perth WA Society for Responsible Design (1990 - ) NSW Re-Design Group Melbourne, Victoria (1991-93).

The Domestic Companion: Taking Stock of Furniture Futures

In 1990/91 the author was commissioned to research and develop a national furniture industry strategy. Examines domestic furniture futures, the concept of home, flexibility, transverse use, product families, trends and future furniture companions.

Exhibiting Furniture

The exhibiting and collecting of contemporary Australian furniture design is a telling indicator of how we as a society regard design. Australian furniture has been seen at SOFA (Sculpture, Objects and Functional Art - Gallery Trade Fair Chicago USA) since 1993.

Lighting Design

Market size in Australia is the main hurdle to successful lighting however there are designers who are making inroads with Australian lighting design.

A Touching Story

Sydney's Powerhouse Museum began collecting artefacts relating to industrial design in the late 1980s. Since then a number of designers and consultancies have been represented in the collection. The author, curator of Industrial Design, Innovation and Marketing at the Powerhouse tells the story of these unsung heros and heroines of the everyday.

Out of the Garden and into the Landscape

What landscape architects in Australia have been doing since about 1970 is to begin to address the Australian lanscape in all its extraordinariness and vastness - as a subject for design and interpretation in the creation not only of our settlements but all those places where we may leave our mark, even if we don't inhabit them.

Designing for the Computer Screen

Design for the new media encourages models which utilise multi-dimensional connectivities. Vertical layering of data is their area of exploration in comparison to the more conventional horizontal depiction of information on the page or in narrative cinema. The grammar of the interface designer has had to alter to accommodate random access and idiosyncratic hierarchies established by the user.

Magabala Books: The Politics of Design

Magabala Books, Australia's first indigenous publishing house takes its name from an indigenous vine that flourishes on the pindan soil of north western Australia. Sam Cook is the publisher's first indigenous designer. She talks with Mara Mann.

Australian Fine China: Artists and Industry

Perth based Australian Fine China, the only maker of porcelain in Australia and New Zealand, is currently using a number of artist-designers to move from being a stolid china manufacturer for railways and cafes to one whose products are seen in top flight restaurants in the big hotels, in classy tourist venues and now on the dining tables of the nation. They have some way to go to entice Australians to purchase the 'local product' for their homes but they are making steady progress.

From the Bush to the Street: A Change in Direction for Australian Fashion

Despite the pull of the outback and the image of the Aussie bushman, the majority of modern Australians are urban dwellers, strung around the perimeter of the Continent. Little known to the outside world beyond our cultural icons of the kangaroo and the koala, few look to Australia as a source of contemporary design in any form, let alone fashion. Until recently, the global fashion market has seen fit to ignore the rest of our antipodean designers.

Indigenous Australian Dyed and Printed Textiles

Textile traditions of indigenous Australians have provided an impressive basis for their current divergent development within the framework of introduced technologies. Looks at various textile producing centres around Australia Tiwi, Ernabella, Kaltjiti, Injalak, Keringke, Ngunga Designs, Warta kutju, Kaen design, Djookan design....

Spots n' Dots n' Stars n' Bars

Australian Textile design from an RMIT perspective surveying current and future initiatives - practice based issues of developing guidelines for copyright in an industry that is known for - in polite terms-recycling and reworking proven designs, to the more speculative concept of creating a dialogue in textiles between Australian and other countries via the internet.

Desert Designs

Based in Fremantle, Western Australia, Desert Designs (begun in 1984) is a concept marketing company that deals with authentic Aboriginal art works and acts as a nexus with manufacturing industries to facilitate their transition into products and their entry into retail markets.

SA Designer-makers Turn to Industry

A unique exhibition curated by Steve Ronayne (owner of Aptos Cruz Galleries) held at theJam Factory Gallery in 1996 'South Australia - Emerging crucible of contemporary design' showed just how many local designer-makers of contemporary craft are adopting industrial processes in their work.

Andrew Carter: Theatre Designer to the World

Andrew Carter is a much sought after theatre designer. He is a creator of innovative sets and has received many presitigous commissions.

The Soft Machine

Interview with Andrew Rogers, Director of the ARID industrial design group (within the University of Adelaide's Research precinct). They spoke about the seductive blurrings of boundaries between man and soft machine.

Furniture Design in Western Australia

The present era of contemporary Western Australian furniture design can be thought of as beginning under the influence of David Foulkes-Taylor (1956 until his death in 1966).

Gifted Arts

In 1992 the Premier of WA initiated the Premier's Gift Commissioning Project in conjunction with the Crafts Council of WA inviting artists to design and produce protocol gifts and souvenirs within a lower price range, which though of exclusive design could be manufactured in multiples using light local industrial processes where appropriate.

Serious Fun

Book review Absolutely Mardi Gras

Jointly published by Doubleday and the Powerhouse Museum

1997

RRP $29.95

Inventive Australia

Book review Know-how, the guide to innovation in Australia

Interactive CD Rom published by Powerhouse Publications,

Powerhouse Museum, Sydney NSW

Macintosh/Windows

RRP $99.95

Seeing a Plant: Being a Plant

Exhibition review Stephanie Radok

Greenaway Gallery, Adelaide SA

11 September - 6 October 1996

Petals on a Wet Black Bough

Exhibition review In Remembrance of Things Past... Angela Valamanesh Jam Factory Craft and Design Centre, Adelaide SA

18 October - 1 December 1996

Loungeroom of Ideas

Exhibition review Messy and Restless: Helene Czerny, Julie Duffield, Paul Hoban, Terri Hoskin, Derek O'Connor

Contemporary Art Centre Adelaide SA

1- 24 November 1996

Out of the Kitchen

Exhibition review Masters Exhibitions 1996

12-28 September: Greg Geraghty, Johnathon Dady, Paul Dryga, Namchou Chitma

10-26 October: Rhonda Wheatland, Amanda Poland, Helen Stacey, Elizabeth Abbott, Brian Lynch

7- 23 November: Greg Fullerton, Danielle O'Brien, Julia McGuire, Harekrishna Bag,

University of SA Museum, Adelaide SA

Wanton Fruits

Exhibition review Barbie Kjar

Dick Bett Gallery,

Salamanca Place,

Hobart Tasmania

26 November - 10 December 1996

Share-house Art

Exhibition review Tasmania art co-op: recent works from Australian Artist-Run Initiatives

The Long Gallery, Salamanca Arts Centre, Hobart Tasmania

15 November - 8 December 1996

The Nature of Perception

Exhibition review Howard Taylor: Paintings and Drawings

Galerie Dusseldorf, Perth WA

1- 22 September 1996

Space Defined

Exhibition review Jewellery by Brenda Ridgewell,

New Collectibles Gallery,

East Fremantle WA

20 November - 1 December 1996