The 17th Biennale of Sydney was very much an experience, a journey of discovery rather than simply another art exhibition. For its curator David Elliott it was the third in a series of exhibitions. (The first was Wounds: Between Democracy and Redemption in Contemporary Art held in 1998 as the inaugural show for the new building of the Moderna Museet in Stockholm, the second was Happiness: A Survival Guide for Art and Life the opening show of the Mori Art Museum in Tokyo 2003, both were co-curated with Pier Luigi Tazzi.) I haven't seen them but their mere titles suggest a definite emotional agenda into the cool field of contemporary art.

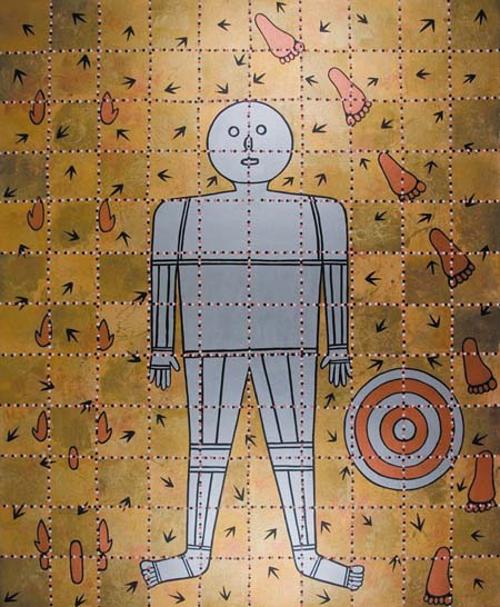

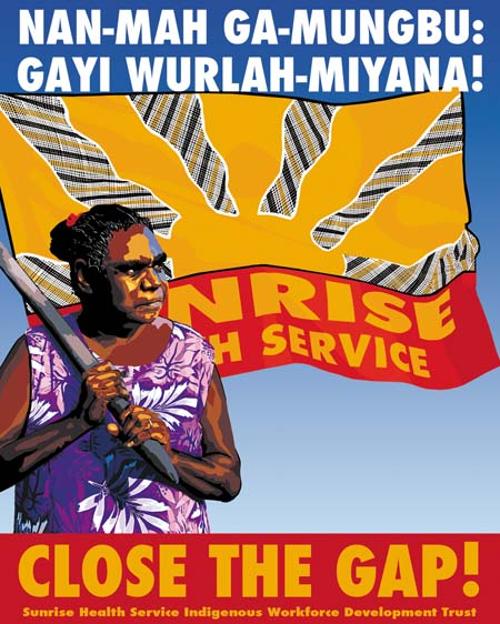

One of Elliott’s trademarks as a curator is the inclusion of work by indigenous artists and in The Beauty of Distance it was there as a particularly strong current. The bookworks Illegal Alien’s Guide to Climate Change (2010) and The Enlightened Savage’s Guide to Economic Theory (2010) by Mexican artist Enrique Chagoya who calls himself a 'reverse anthropologist’ were just the beginning. The 110 Larrakitj by 42 Yolgnu Artists were a beating heart of contemporary indigenous knowledge.

Elliott’s comment at the press conference and exhibition launch that the Biennale needed to compete or live up to the bats living in the Sydney Botanic Gardens was a clear sign as to where his sympathies lie, like Joseph Beuys, with the animals and with Mother Earth. A certain amount of ‘hippie’ ideals are definitely present in the Biennale - though very well-organised and useful the catalogue is pure psychedelic counterculture. And as an old hippie friend of mine is wont to say: ‘The hippies were right!’ (i.e. treading lightly, ecology, saving the earth, listening to indigenous peoples, trying to not be greedy and materialistic, sharing the world are all themes foregrounded in the Sixties and now considered almost mainstream, certainly desirable). Elliott likes to say that we are at the end of the age of Enlightenment.

UK artist Marcus Coates’ Song Cycle and his Pub Shaman with his animal headdresses, animism and psychic experiments, Annie Pootoogook’s cartoons of daily life among the Inuit, sometimes alcoholic or violent, in the Arctic, Fiona Pardington’s eloquent Ahua: A Beautiful Hesitation (2009) black and white photographs from museums of casts of Pacific, Maori and French heads that speak of colonialism, museums, anthropology and phrenology, Louise Bourgeois’ intense white-painted bronze casts of her old jumpers twisted into morphically resonant shapes that somehow echo South African Nandipha Mnambo’s sculptures made from cowhide that resemble iconic Greek sculptures like the Venus de Milo or the Nike of Samothrace, each draw in aspects of the lives of indigenous peoples and shows them as having both pasts and presents that are now being written into history. This is post-Enlightenment thinking where rationalism is not considered a dominant ideal, where the hierarchies established by Diderot’s Encyclopédie are shown to be constructed and where non-Western peoples’ ways of seeing and managing the world are given space.

Then there are the implacable forces of nature as represented in Shen Shaomin’s Bonsai pressing up against grates and the fractal electrical energy patterns of Hiroshi Sugimoto’s Lightning Fields.

In the journey of the Biennale it was of course Cockatoo Island that was the star. The point of showing art in a place like Cockatoo Island is that you don’t know the spaces, don’t know where the doors and windows are, don’t know where you are or where you are going. There are two possible approaches to this, one is to get the map and work your way as systematically as possible from work to work, crossing them off as you go. This approach seems to consider art as a competition that you can win or lose. The other way is simply to wander thus being prepared to miss something or indeed to find something that is not on the map at all. That this is more likely to happen in a non-gallery space goes without saying. Opportunities for reverie were full-on at the Island thus it was possible to conceive of the Island as a kind of waking dream, something private, something immediate, something insubstantial that you could wake up from or you could pursue, preferably alone so as not to break the dream, at your own pace. Thus in some way an ideal experience of art as enveloping more than the mind and the eyes and ears but also the body, the memory and all the rest of the senses including the sense of survival. That old refrain ‘you’ll never get off the island’ made you aware of the ferry, the time of day, the edges of the island, and yet it could have gone on forever.

In the undemanding work by Finnish artist Ola Kolehmainen of blurry images of Sydney landmarks it was easy to maintain a trance-like state, a condition that may perhaps be compared to the immersive melding of dance, song and visual art found in indigenous cultures. On looking at this work it was the darkness of the sheds, the apparent lack of concern for occupational health and safety (risk/danger) and the multiple pigeonholes surrounding it each with the name of the parts or tools once used there that kept a sense of dream and unreality going. And then I saw it, a fine grained camera obscura image of shifting clouds outside in the sky reflected on the ground – a happy accident, a hole in the corrugated iron that the artist did not create but which lent the work a supernatural strength.

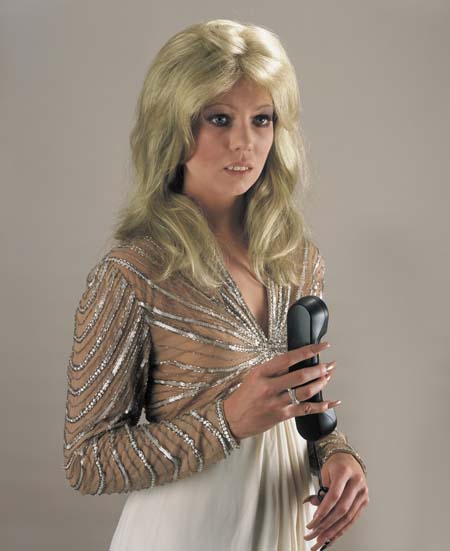

Then there were the things that made the hair stand up on your body like the videos shown in tightly confined spaces, one by Guetamalan Regina Jose Galinda called Confesión (2007) in which the artist is tortured by being waterboarded or Argentininan Miguel Angel Rio’s Crudo (2008) in which a dog attacks a man. In each work the South American sensibility of knowing and not faking extremity is terribly present. And then hung on the walls in the old empty houses there were suburban memories dragged up by Alex Danko’s Cultural Meditations (1949-2010), patterns of Ukrainian folk embroidery in which entire worlds are held, or the unblinking humourous retro horror of Yvonne Todd’s photographs of strange goofy women. And the three astonishing and poignant photographs by Finnish artist Tiina Itkonen of Qaanaaq, Kullorsuaq and Uummannaq in Greenland, showing mountains, ice, sea and human settlements. She has been taking photographs there since the mid-90s and her images document climate change as well as showing the incredible beauty of the land, human steadfastness and fragility.

Later I thought about the idea of having a people or being a people – the very base of culture as it is represented to us by indigenous people. Looking for your tribe, empathy, being aware that your people are all the people of the earth – this is the meaning of survival.