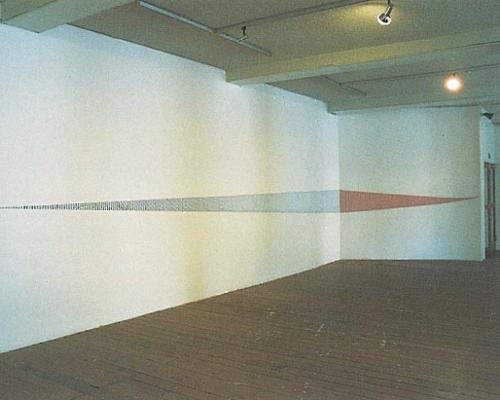

It would be a mistake to think that Brian Blanchflower has lost interest in installation art, and unequivocally declared his hand as an abstract painter. In this exhibition of paintings from the previous decade, he emphatically asserts the architectural and even kinaesthetic presence installation aspires to. Indeed, the most striking piece in the exhibition, Threnodies (in 5 sections), is patently a painting installation.

The sense of architectural space is so convincing that the paintings I found less successful did not detract from the overall force of the exhibition. It is accurate to talk of a force, rather than say a narrative, because each painting and group of paintings is, like the exhibition as whole, held together by a palpable energy field that seems natural in origin. This condition of nature rather than art is the fiction which stages Blanchflower's art. This does not mean he is indifferent to painterly matters. The exhibition is a goldmine for painting teachers and students interested in the artifice and craft of painting – just look at the Painting Books. Only a few artists in the world today 'see' as incisively as he does – so incisively that he takes paintings places where the eye can't go. Much like the experience of being in a forest or the ocean, we seem to bodily inhabit the paintings' energy fields. Blanchflower makes this nature-painting so believable that the painterly contrivances he uses are here quite forgotten – or his paintings work best when this is the case. Then, as in nature, the order is an indeterminate and ineffable presence rather than imposed.

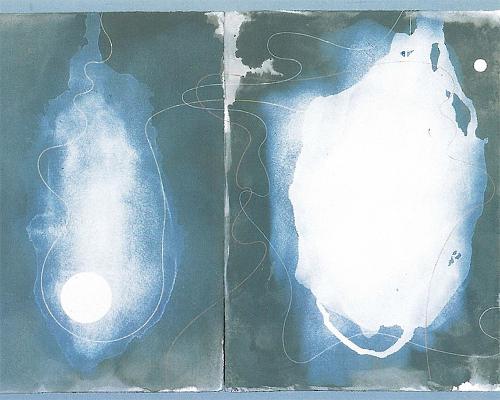

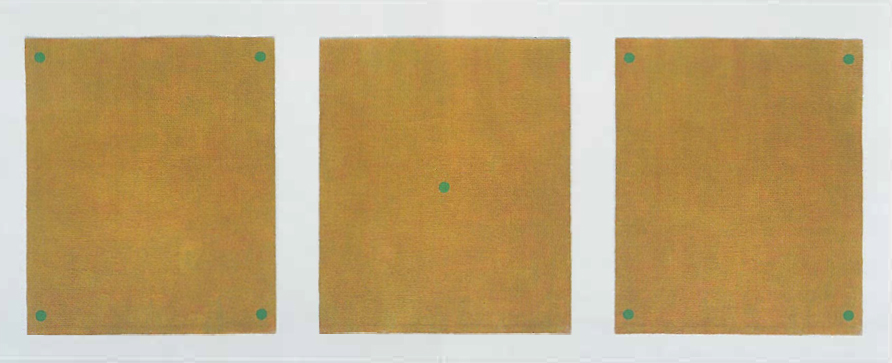

Two stunning large paintings from the early 1990s physically dominate the exhibition. Canopy XX111 is perhaps the more satisfying, but for me Canopy XXV111 is the more interesting because the order he finds in this painting emerges almost entirely from the apparent arbitrary chaos of marks and shifts across the canvas. However, to my mind, a grid of small red dots unnecessarily orders its space, as if the artist did not have the confidence to allow the rhythms he initially unleashed do their work. For many years Blanchflower's paintings have been characterised by a grid of circular marks morphing into a more open space, and, for me, the less obvious the work of this grid the more successful the paintings. Recent experiments with such a grid pattern in the spectacular triptych Canopy LVI left me undecided. While the colour zings, the placement of the green circles seemed optically contrived.

Blanchflower's mastery of colour is the strength of this exhibition. He precisely judges its tone and the atmospheric presence generated by the scale and surface of its support. This is true for all the paintings, but is most compelling in the monochrome canvases, such as the slow shifting smoky grey light of Canopy LI (Scelsi I-IV), and the hallowed altar-like installations, The Gift of Silence and Threnodies. In the latter, five minimal canvases of various sizes and hues are asymmetrically arranged in a small room. The effect, however, is far from minimal. It has all the baroque drama and spiritual call of Caravaggio's Cerasi Chapel, even if the means and the tune are very different.

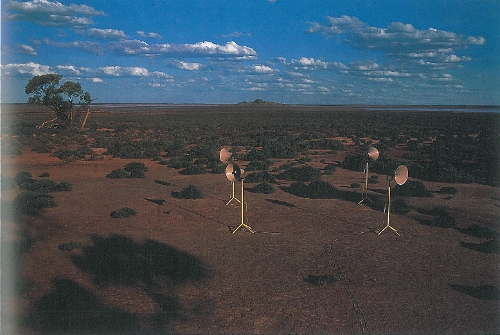

Painting is usually considered the most visual of the arts, and it has prospered when visibility was the centre of belief. However Blanchflower returns painting to its origins in architecture, dance, song and ceremony. He is on record as saying that the only Australian art which interests him is Aboriginal art. While some might discern a stylistic dialogue between some of his work and Aboriginal desert painting, it is better to speak of a rapport. Drawn to the hidden and alchemic order of things rather than the politics of representation, his work is profoundly uninterested in issues of style, and is a-historical in intent. This is not to say temporality is not an important factor in the experience of his work. However it is not an historical or linear temporality. Rather, he bends time into the space of his work, as if they are one and the same, thus enhancing the fiction of his paintings being natural rather than cultural artefacts. However, with whatever fictions artists lure us, none escapes their time or its politics of representation. Like that other great Australian abstract artist of the 1990s, Emily Kngwarreye, Blanchflower's apparent persistence with a supposed outmoded medium and style confounds us with its contemporaneity, with its pressing relevance at a time when nature's fundamental forces aggressively assert their presence in our lives.