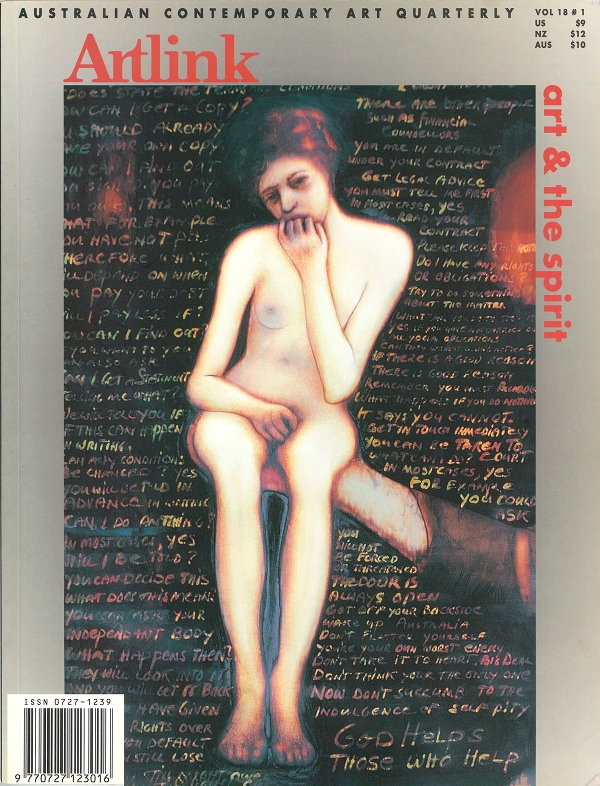

Art & the Spirit

Issue 18:1 | March 1998

Wide-ranging responses to issues of spirituality in the visual arts. Looks at the role of indigenous art and its relationship to land. Examines significant contemporary exhibitions addressing art and the spirit.

In this issue

Vi$copy Rules. OK?

In 1972, when I began work as curatorial assistant at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, artists in the collection had no formal written rights to their work. Each time a work was acquired by the gallery, the artist was sent a pink copyright form which they were expected to sign, even though this relinquished all their rights and assigned them to the gallery.

Urinating to Windward

Artists asserting a commitment against ignorance have recently called for the resignation of the Director of the National Gallery of Victoria.

There seems to be no particular matter of fact about which Dr Potts stands accused: his ignorance relates somehow to an issue of principle that was flouted (as his critics assert) when he prematurely closed the exhibition in which Andres Serrano's photograph, Piss Christ, provoked some complaint, some minor violence and (as we are told) unspecified threats.

Art, Trash and Religion: the Serrano Affair revisited.

Who would have expected that Piss Christ would spark off a major public row in Australia, eight years after it was originally made notorious in the United States?

Wrestling with Difficult Issues

The Jewish Museum of Australia is almost certainly the only religiously based institution in Australia which provides a contemporary art space. An important role of the Museum is to define an Australian Jewish identity, but in the contemporary space the Museum also helps to shape this identity. As well as celebrating our eternity in our permanent exhibitions, we help to forge our future by having contemporary shows.

Beyond the Bleeding Heart...

Rosemary Crumlin discusses the sacred and the secular in contemporary art, starting with the exhibition she curated at the National Gallery of Victoria

The Spiritual, the Rational and the Material: Spirit and Place Art in Australia 1861 - 1996

Since 1984 there have been five major exhibitions which sought to engage aspects of the spiritual in art and which attracted international comment. Spirit + Place, Art in Australia 1861 - 1996, which opened at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Sydney on 22nd November 1996 and closed on 5th March 1997, was the most recent of these.

Spirituality in Contemporary Australian Art: Some contexts and Issues in Interpretation

While there is a return to spiritual interests internationally in the Western world (from the counter culture of the late 1960s to the present) the 'spiritual' has been until now, relatively ignored in the interpretation of twentieth century artists work.

Where Eagles Hover

Any discussion of the sacred and spiritual in Australian art must surely defer to the art of Aboriginal people for theirs is the art and culture which speaks most directly and profoundly about the connection of human spirituality to the Australian landscape.

Grandmother's Mob and the Stories

Julie Dowling interviewed by Lavinia S. Ryan

In the past five years, after graduating from Curtin University, Julie Dowling has been painting professionally. Recently Julie took part in the artists' forum, Wijay Na? (which way now) for the Northern Territory Centre for Contemporary Art.

Groundwork - New Work/Old Law: The Spirit of the Land in Three Communities

The embracing of new mediums like artglass and the encouragement of new artists demonstrates the contemporary nature of Aboriginal art and culture. The art reflects profound connections to place and to the past, connections that continue to be spiritually significant. Three Art Centres come together in an exhibition for the Festival of Perth to show that Aboriginal culture is a living cullture.

Embodiment: Concerning the Ontological in Art

The exhibition The Painters of the Wagilag Sisters 1937-1997 is a historic landmark in the exhibition of Aboriginal art in Australia. A collaboration between three curators, Wally Caruana, Djon Mundine and Nigel Lendon, as well as with the contributing Yolgnu artists, landowners and custodians from Central and Eastern Arnhem Land the exhibition confirms the significant role of the National Gallery of Australia in collecting, presenting and promoting Aboriginal art.

Collaboration by Satellite

Satellite link-ups between continents have upped the telecommunication ante, intensifying the exchange of ideas and impressions by participants. The sense of sight is now added to the teleconferencing capacity for hearing everyone at once, making it easier for participants who have never met to know who is speaking when, and simplifying the task of managing a given session.

Susan Hiller: Being Rational about the Irrational

Visitors to the Adelaide Festival will be able to see From the Freud Museum and Wild Talents. at the Experimental Art Foundation from 26 February recent works by visiting London-based artist Susan Hiller. Cath Kenneally spoke to her in London about her history and her art.

David Jones' sculptures in the landscape - a spirit of place

Spirituality in western art is not necessarily ecclesiastical. There are artists who make work which is imbued with a deep spiritual connection to the land. The works may be temporary, ephemeral installations surviving only in the photographic record or they may be of more permanent substances.

Cedar Prest: Community Art and Spirituality

For Cedar Prest, stained glass work always begins with a meditation on what she terms the "light atmosphere" of a particular place. This is not simply the physical presence of a source of light and its intensity within a room or particular architectural space, but also the more complex sensual influences that determine the way light enters a particular space through one or more "holes in the wall".

Migration and Faith: Places of Worship in a Multicultural Community

"The cosmopolitan character of the residents of Australian cities has often been shown and it is in their worship that the various nations represented in our midst receives most definite demonstration. The Greek Orthodox Church has a small but increasing community in Melbourne, numbering about 150 Greeks and 50 Syrians, and it is now decided to build immediately, at a cost of about $3,000 a new Greek Church".

Maria Ghost: Rick Martin

Experimental Art Foundation Adelaide SA

December - January 1998

The Measured Room

Di Barrett, Mark Kimber, Deborah Paauwe, Toby Richardson Contemporary Art Centre of SA

1 October - 2 November 1997

Caboodle: Work from the Jam Factory Studios

Jam Factory Gallery SA

Ceramics, Glass, Furniture, Metal

14 November 1997 - 11 January 1998

Tripping the Light: The Big Party Show

Curator: Robyn Daw

Artists: Cath Barcan, Christl Berg, Barbie Kjar, Greg Leong

University Gallery, Launceston Tasmania

8- 31 August 1997

Sea

Curated by Romy Wall with David Hansen

Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, Hobart Tasmania

28 November 1997 - 4 January 1998

Fremantle 6160

Fremantle Arts Centre

18 October - 30 November 1997

Swingtime, East Coast - West Coast: Works from the 1960s-1970s in The University of Western Australia Art Collection

East Coast 22 August 1997 -1 February 1998; & 10 April - 27 September 1998.

West Coast 22 August 1997 - 21 June 1998.

Lawrence Wilson Art Gallery

The University of Western Australia, Perth.

Building a picture: Interviews with Australian Artists by Gary Catalano

Published by McGraw Hill Australia 1997

RRP $36,90

Artrave

vis.arts.online