It was a warm autumnal morning as I joined the commuters on the journey into Canberra’s Civic Bus interchange. There the Affective Labourers Union had installed itself with a bear suit, A-boards and high-visibility vests for their Civic Interstrange project. Following the instructions on the A-board, I texted a description of my mood to the number listed, and moments later a Union member could be seen painstakingly copying my status update onto the whiteboard that hung from another Labourer’s neck: ”Feeling light-hearted … Every last warm day counts”.

The program for the You Are Here Festival describes the project as “real time insight into the emotional undercurrents of strangers”. Surrounding the optimism my one-off commute has inspired, messages from those in the daily grind are less joyous: “I feel like there’s a trombone stuck inside me …”. This intervention on Canberra’s streets is one of many launched by the 2016 You Are Here Festival, and it reflects the decidedly grass-roots, low-fi approach of many of the works in this curated, artistic forum. References to “on-site” and “real-time” echo the vernacular of the data-connected lifestyles of Canberra’s citizens. But the artworks subvert digital association by generating face-to-face, intimate public spaces for personal relations.

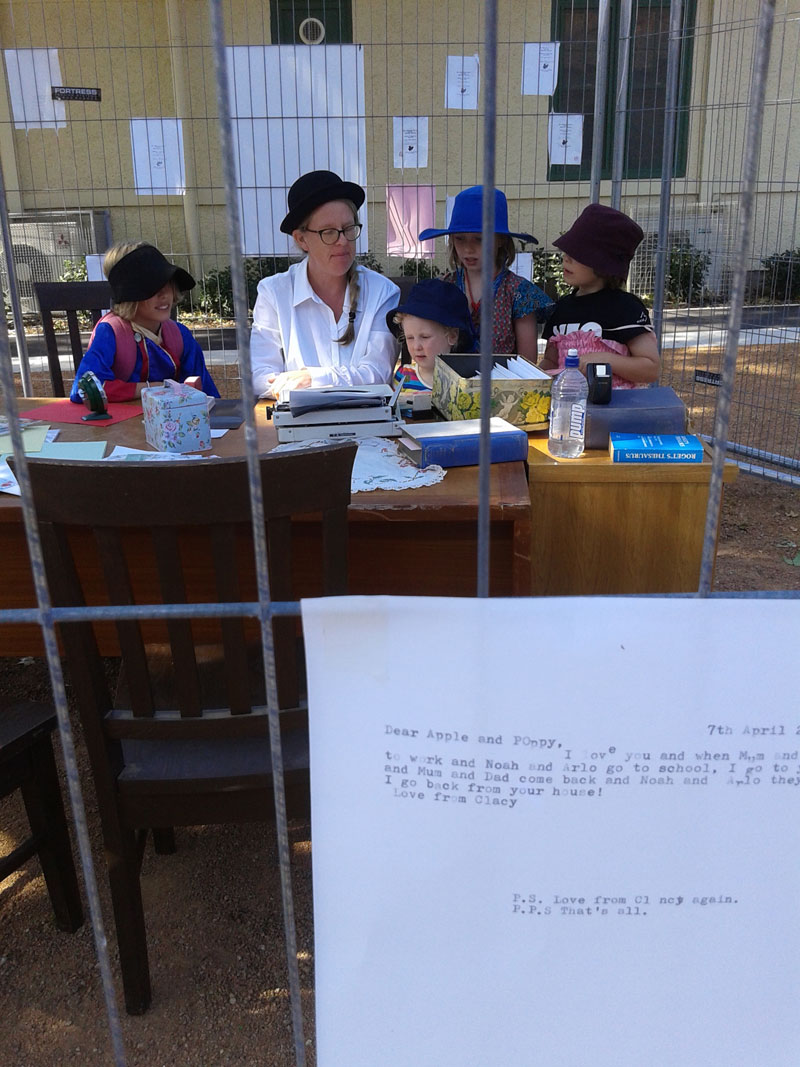

At Gorman House, the “Out of Space” project presented two works of art that present very different approaches to public space. Ms Constance Spry’s Letter Writing Service re-connected letter writers with communications technology of the past, by way of a clunky typewriter and reams of decorative stationery, set in a courtyard under a tree. Under assistant letter-writer Ms Lucy’s tutelage, my tribe of small people was as intrigued by the process of typing missives of birthday good-wishes as they usually are by swiping emails into my android. An hour of letter writing later, the same tribe ran under Chris “Walrus” Dalzell’s curving structure Contain(ed), with barely a nod to its rough, minimally crafted assembly of wooden struts. While I enjoyed finding different angles from which it could frame the bright blue sky, the lattice-like assembly represented one of the more conventional artworks that viewers might encounter in You Are Here. The domestic scale of Contain(ed) suggested it might be just as at home in a backyard garden covered in grapevines.

On another warm autumn day during the festival, I found myself wandering through Garema Place as dusk fell. Amongst the usual loitering teens and their performative swearing, I encountered two limber young women dancing with potted plants. Alison Plevey and Olivia Fyfe’s choreographic guerrilla gardening performance Sprout attracted the full attention of flâneurs in the mall. Around a pile of dirt, and accompanied by soaring classical music, they hoed, raked, dug, planted and watered with joyous abandonment, their grotty overalls disguising the precision of their movements. Intervening on the grey paving of the mall, which at the best of times contrasts oddly with the deciduous trees that soar up out of the pavement, Sprout drew attention to the tensions between the natural world, the built environment, and our fragile human selves “in our urban, concrete and digital vortex”. It brought texture and depth to an ordinary weekday evening in the city, yet another indication of the creative life bubbling to the surface.

One of the more antagonistic gestures in You Are Here was Bernie Slater’s “Power” installation at Canberra Museum and Gallery (CMAG). The installation took over an adjacent shopfront-like space, so it would have been easy to pass by the window display without realising that the hundreds of identical boxes on display did not contain the latest technological device. Those who opened the door and entered were invited to claim a free box of political commentary and provocation. Inside was a series of works on paper in decreasing sizes – from an unwieldy folded map/poster down to handy booklets and cards. Utilising digital collage to appropriate and combine snippets of print media news from recent “nontroversies”, advertising, packaging and his own illustrative drawings, Slater reproduces absurdity on a mass scale. These works are simultaneously critical and incredulous, intriguing and humorous, yet they raise a sticky question: do they preach to the choir? Slater is all too aware of this trap, and the smallest of the works in the box represent his endeavour to avoid falling into it. Two credit-card sized stickers slip of a casing titled “Gateway Behaviours”. One offers a blank speech bubble, the other a messy red scribble: both should be applied, the packaging suggests, to something that needs to be scribbled out or spoken over – for instance, the incessant abuse of refugees, casual racism or formal surveillance.

The 2016 You Are Here Festival deals predominantly with “first world problems”. The woes of being trapped in a welfare state, the perils of being constantly connected, the attendant encroachment of society and corporate interests into our personal life, all generated sensitive and thoughtful responses from artists attuned to the undercurrents of social unease and discord in a privileged nation. But Bernie Slater’s “Power” project is a reminder that our first world problems extend into other worlds, and our introspective disillusionment can visit devastation far beyond the angst of our morning commute. We can only hope that taking up his “gateway behaviours” might extend the positive impact beyond social media networks.