Lesbian and gay visual art in Sydney has made the long trek from appearing solely in subculture venues or alternative spaces to exhibitions in prestigious commercial galleries or art museums. There has always been a market for mainstream-museum and marketcertified homosexual artists such as Warhol, Hockney, Haring and Mapplethorpe, and the local equivalents including Juan Davila, Jeffrey Smart and Donald Friend.[1] However, the work of many other gay and lesbian artists was considered too risky to be shown in mainstream galleries. The acceptance of group shows clearly identified as involving gay and lesbian sensibilities in these mainstream venues is, in part, due to the decriminalisation of [male] homosexuality and legislation which was recently [1984] passed in New South Wales to prevent the vilification of homosexuals or to prosecute those inciting violence against them. But the strong visual presence of the lesbian and gay community has also made Sydney a major centre for lesbian and gay art.

Sydney's reputation as a hedonistic city, which is centred around lifestyle has encouraged the belief that there is an easy tolerance of difference within the community. This tolerance has extended in limited ways to an acceptance of sexual diversity and has encouraged the growth of large and visible gay and lesbian enclaves. Oxford Street at Taylor Square and now King Street in Newtown have developed extensive commercial centres to cater to this community. There is an expression of camp aesthetic through the many shops selling goods ranging from postcards to leather. A lively bar scene, cabarets and enormous dance parties especially the annual Sleaze Ball attract increasing interest from heterosexuals looking for stylish and ebullient entertainment.

While there is a degree of tolerance from the heterosexual majority it still does not mean that it is safe on the streets for lesbians and gay men. Homophobia is still strong. Lesbians and gay men continue to be assaulted and murdered with appalling frequency. Nor is it easy for many artists to declare their sexuality for fear of discrimination or being categorised as "just a lesbian or gay artist" and thus marginalised in the art world.

The major expression of the community's creative spirit is through the Sydney Gay & Lesbian Mardi Gras Festival. This is an Arts Festival of extraordinary breadth including not only the visual arts but performing arts, cabaret, forums, community events and an outdoor, night-time parade of unrivalled flamboyance along Oxford Street through the heart of the gay community in Sydney. The Festival began in 1978 when lesbians and gay men in Sydney held a political rally to celebrate the New York Stonewall riots which were the beginning of the modern gay liberation movement in the US. This first street march resulted in violent confrontations with police and the arrest of 178 participants. The marches continued with the first summer parade in 1981 and a few years later one performing arts piece was included in the week leading up to the Mardi Gras Parade. This was the beginning of the present Arts Festival.

By 1985 mainstream media and some politicians wanted the parade and party banned because of the AIDS issue. They conceptualised AIDS as the New Plague and homosexuality as the source of infection. The theme that year was Fighting for our Lives, which summed up the impact of AIDS on the gay and lesbian community in their efforts to confront this crisis. Not only was the community suffering the illness and first deaths from AIDS but there was a violent backlash of homophobic rage against all homosexuals.

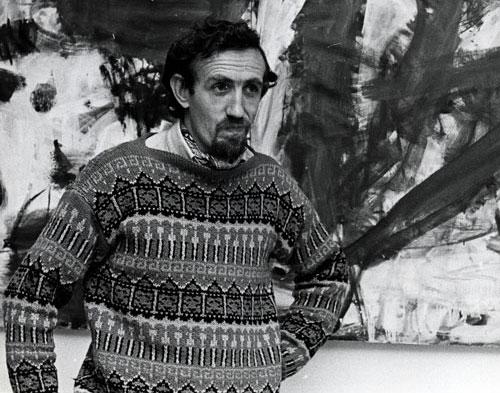

AIDS also challenged the basis of gay identity as lesbians and gay men are defined through their sexual preference and sexual practices which express this preference. Particularly for male activists gay liberation meant sexual freedom. With the advent of AIDS these promiscuous and radical sex practices which had formerly signified freedom, were now possible ways of spreading the AIDS virus. Thus AIDS was not only a health crisis but a crisis of identity. Through the transformation of their sexual practices into safe sex, gay men are now able to protect their lives as well as maintain their identity.[2] Individual artists including David McDiarmid, whose work has been used on posters advocating safe sex, as well as groups such as ACT UP (Aids Coalition to Unleash Power) have engaged the visual arts as a political practice.

.jpg)

Even if this increased media reportage of the gay community was negative and biased, it increased general community awareness of homosexuals and their parade. This is reflected in the increase in the estimated crowd size of 30,000 at the Mardi Gras in 1985 to 600,000 viewers at the 1994 Sydney Gay & Lesbian Mardi Gras Parade. The 1994 street parade contained over one hundred and thirty elaborately decorated floats, several synchronised dance groups and numerous individual costumed marchers. Traditionally the Dykes on Bikes lead the parade and this year won the award for the best non-commercial float. An hour-long edited program of this parade was shown on True Stories, which drew the largest-ever viewing audience for the ABC on a Sunday evening.

An economic impact study in 1993 suggests that an extra $38 million is poured into the economy by these events, which may well be the incentive for the mainstream gallery system to take the risk of showing gay and lesbian art. In contrast to the Festival in the early years, the 1994 Sydney Gay & Lesbian Mardi Gras Festival included 21 gay and lesbian art exhibitions listed in the official guide. Consequently the audience for gay and lesbian visual art activities is now large by any standard. However the increasing mainstream intrusion into Mardi Gras coupled with a "growing commercialisation and professionalisation of the event" raises concerns that the potency of the political comment and the explicit homosexual nature of the work may well be diminished or erased in the future.[3]

This year within the parade and in the galleries, issues of importance to lesbians and gay men were confronted at a wide range of exhibition spaces. These ranged through bars, cafes and theatre foyers to established artist-run spaces, commercial galleries and publicly funded institutions. Community venues were chosen by many artists to bring their work to specifically homosexual audiences. The Stronghold at the rear of the Clock Hotel again this year hosted the leather and mixed media images of Marcus Craig and the Solea Cafe showed Carrie Maguirre' s photographs of classic gay resorts such as Fire Island.

However other artists used more mainstream venues. For the last two years Barry Stern Gallery has shown the work of the more established gay artists and again this year showed artists, including David McDiarmid. Campbelltown City Art Gallery curated (+) Positive, an exhibition by several artists, including Brad Levido, Phillipa Playford, William Yang and Harry Wedge. The exhibition addressed issues concerning AIDS, including Aborigines and HIV, safe sex and lesbians. It is a significant event in the development of lesbian and gay art that a publicly funded city gallery would mount such an exhibition. (+) Positive won the Mardi Gras award for the outstanding visual art exhibition of 1994.

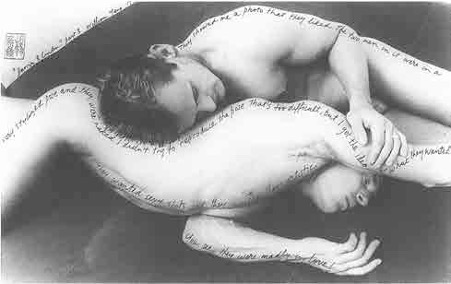

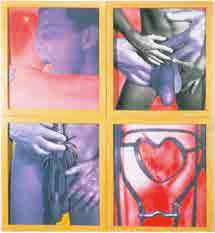

At the Blaxland Gallery in Grace Bros department store, a more varied audience could view the work of around thirty artists using photography to demonstrate the "heightened profile of queer artists within corporately-funded mainstream visual culture".[4] Several other exhibitions explored issues of photography in conjunction with aspects of pornography. At the Martin Browne Fine Art Gallery, together with the Australian Centre for Photography and part-funded by the Sydney Gay & Lesbian Mardi Gras, were the self-depictions of the French surrealist artist Pierre Molinier as the "Divine Hermaphrodite" . These photographs and photomontages made in the period between 1965 and 197 6 are important images in the depiction of queer identity. In Shan Short' s catalogue essay which accompanied the Queerography exhibition at the Roslyn Oxley 9 Gallery, 'queer' is seen as promising " . . . a refusal to apologise or assimilate into invisibility. Queer can be seen as providing a way of asserting desires that shatter gender identities and sexualities, in the manner some early Gay power and lesbian feminist activities once envisaged." However many of these lesbian feminists are critical of works like Pierre Molinier' s which involves the eroticism of dominance and submission. Sheila Jeffreys recently wrote "The eroticism of sadomasochism derives from the eroticised dominance and submission of institutionalised and unequal heterosexuality." thus "it carries serious dangers for all women".[5]

Joyce Fernandez points out that when the magazine On Our Backs was first published eight years ago, with explicit images of women having sex and the practice of lesbian sadomasochism, many feminists were affronted as "the idea of women producing, purchasing, and getting off on leather and lace and into lesbian bondage was outrageous to a generation of feminists steeped in a consciousness of non-violence, equality, the rejection of stereotypes and the empowerment of women".[6] Lesbian artists exploring female desire can find themselves in the vortex at the intersection of issues of feminism, pornography, aesthetics and censorship.

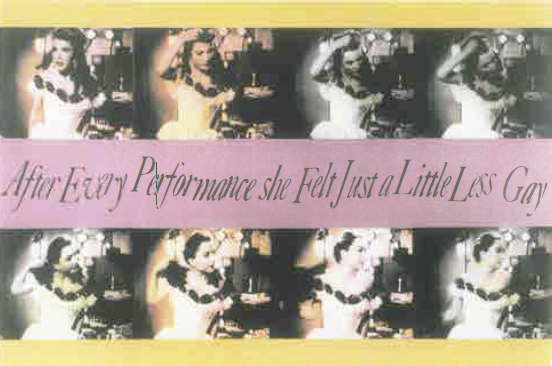

Queerography is similar to many exhibitions within the festival in that it continues to develop and extend issues raised in an earlier exhibition in 1993. In this case it was the show Luscious Orgasmic Vivacious Ecstatic (L.O. V.E.) that publicly presented images of sex as pleasurable. Shan Short points out that a heterosexual audience may have problems in accessing this work because when the artists in Queerography trace over the territories of porno/photography they do so, not only from the place of bodies and sex, but from the regions of sexual minorities and marginalities, the places of difference(s), which brings into question the relationship between queer cultural productions and audiences with no familiarity with the conditions which have shaped them. While Pierre Molinier used bondage, drag and other sexual fetishes in his set pieces, these artists create complex and layered images using a range of photographic techniques. Lachlan Warner uses magazine images, ink and acrylic paint to produce an enigmatic absence of the male figure. Rod McRae combines a range of traditional techniques with current technologies, such as silver gelatine prints with colour laser copies, to produce a series of icons of male homosexuality. In a similar mode C. Moore Hardy explores stereotypes from the straight community to reveal aspects of lesbian identity. The joint works of Lisa Zanderigo and Kaye Shumack plunder sources in popular culture to produce ironic comment in their type C photographic prints.

There is a strong interest among some lesbian photographers in manipulating the image using computers. As the computer is an integral part of male technology, they see it as important that lesbians master this instrument to generate and manipulate their own images. Linda Dement, Rhea Saunders and Michele Barker, all use computer generated images that challenge the displacement of women within technology. In opposition to the more tightly curated mainstream shows, two large community-based exhibitions took place last year. Fifty artists participated in Out Art '93 and more than a hundred lesbians participated in Word of Mouth III. This year around thirty-five artists participated in Out Art '94 at Open Ground, Surry Hills and again large numbers of lesbians participated in the Word of Mouth IV exhibition.

Because of the long history of lesbian invisibility in the visual arts, the Word of Mouth (WOM) collective is committed to "the process of resourcing, outreaching and supporting lesbians to represent themselves in the arts".7 This year's exhibition, Bound for Desire, again endeavours to break down notions about who is able to make art. So both practising lesbian artists and those previously 'un-art-skilled' are encouraged to exhibit, to provide "an anarchic, lesbian grass roots community initiative" . The works exhibited cover the range of visual arts and also include the community projects Lovely Mothers' Posters and Lovely Mothers' Billboard . As the depiction of lesbians in the media and their representation in art has usually been by men, the image of the lesbian has been stereotyped and frequently demonised (ie the Lesbian Vampire). If their sexual preference is revealed, many lesbian mothers face loss of custody of their children. These posters and billboards are funded by the Community Cultural Development Board of the Australia Council and depict lesbians with their own children or with their mothers in ways that they wish to be represented. Last year Word of Mouth III won the most outstanding Festival event. This year, during February and March, the Billboard sites were on railway platforms and in light boxes at major rail stations at Town Hall, Redfern, Bondi Junction and Parramatta.

The Sydney Gay & Lesbian Mardi Gras has provided a focus and support for visual artists in Sydney. It is interesting to speculate whether Mardi Gras can survive its continuing growth and acceptance to maintain its critical edge within the arts. Or alternatively can these gay and lesbian artists continue in the mainstream art world without the support of Mardi Gras?

Footnotes

- ^ Harmony Hammond 'A Space Of Infinite And Pleasurable Possibilities' Joanna Frueth, Cassandra L. Langer and Arlene Raven (eds) New Feminist Criticism HarperCollins, 1993, p 109

- ^ Joyce Fernandez 'Sex into Sexuality' Art Journal, 1991 Vol 50:2, p 37.

- ^ Kim Seebohm 'The Nature and Meaning of the Sydney Mardi Gras Party in a Landscape of Inscribed Social Relations,' Robert Aldrich (ed) Gay Perspectives II: More Essays in Australian Gay Culture, University of Sydney, 1994, p 196.

- ^ Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras Guide, 1994, p 5.

- ^ 'Sadomasochism, Art and the Lesbian Sexual Revolution in Art', Artlink 14#1, p 21.

- ^ Op cit. 7 WOM Collective statement, Word of Mouth Catalogue