It was ‘a middle summer’s spring’[1] almost two years ago – 8 November 2019 – when Fiona Lee’s home burned down. That makes her a number and her home one of 2,439 homes destroyed in NSW from a total of 3,094 nationally.[2] Multiply the average of residents per household and estimates of immediate post-fire homelessness would have come in around 10,000 people. And then there’s the animals’ homes, habitat being so much harder to measure. We’ve read and heard of losses in the m/billions and species pushed close to, perhaps over the edge to extinction. But I’m neither statistician, scientist nor politician, for whom soft, hot facts are data, actual and malleable, respectively. Fiona Lee is an artist and activist, with no great divide between her politics and practice. To be clear: her own real-life embroilment in the events documented here did not push her towards outspoken climate activism. It pushed her back into her artmaking – a practice she had largely turned away from after completing an Honours degree at the University of Newcastle a decade ago. Hers was a conscious decision, turning away from the artworld’s careerism at odds with her more immediate grass-roots work addressing climate change. Most of us are allegorically speaking, passive canaries in the coalmine, chicken-little on the side. But Lee had a phoenix-style fate thrust upon her, as if a messenger. ‘How now, mad spirit?’ she has likely asked, in the post-trauma of ‘the haunted grove.’

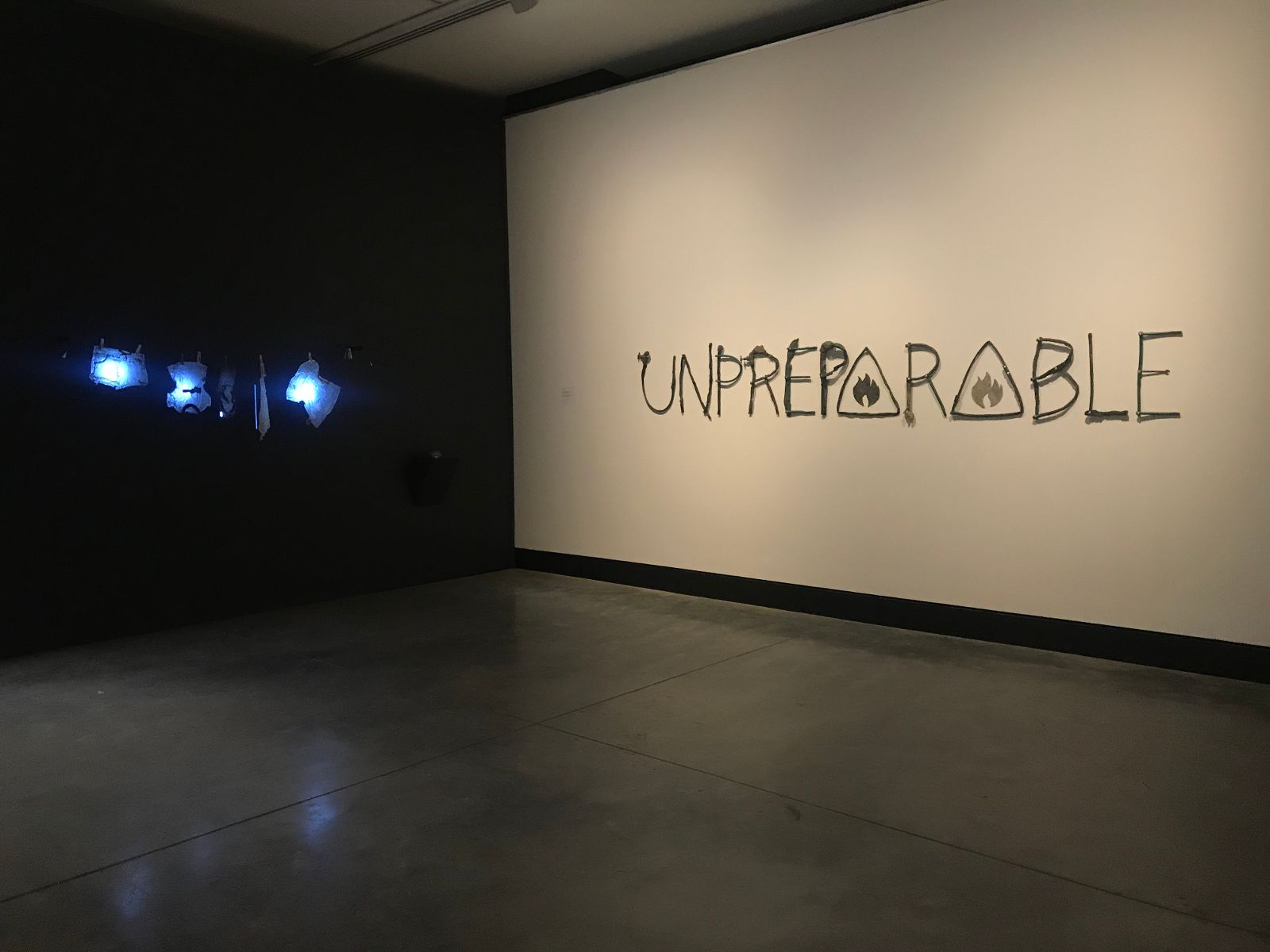

Lee’s Unpreparable at Maitland Regional Art Gallery (MRAG) has its clichés. They need repeating, because the personal is highly political in this literal, visceral catharsis. This is not an exhibition of cacophony – the installation is there-but-spare, the audio just a little too low to be sure the distant faarck … faarck … in the firestorm video (shot by a neighbour during the nightmare) is not the cry of burning crows. But make no mistake: Unpreparable is a call to arms, aimed at state, federal and global forces of bipartisan inaction. ‘Thou shalt not from this grove/Till I torment thee for this injury.’

The titular Unprecedented Fires and a Garden Hose (2021) is nailed up directly on the gallery wall, scraps of tap and garden hose (that suburban promises of survival), tortured by the heat and impotent in the end. Resurrected, the refuse forms the word UNPREPARABLE, a direct response to an unprecedented fire event. In full caps, it hollers, refusing the oblique inference to poor choices and a politic that sometimes blames the victims: failing to prepare is preparing to fail. If ‘unpreparable’ is the new reality, ‘unprecedented’ became the most-abused word of the season, until the solar flare of coronavirus came, quickly replaced by its perennial, less summery name, COVID-19. Those relentless media images of flames and smoke-haze were fast superseded by masked talking-heads and hospital beds.

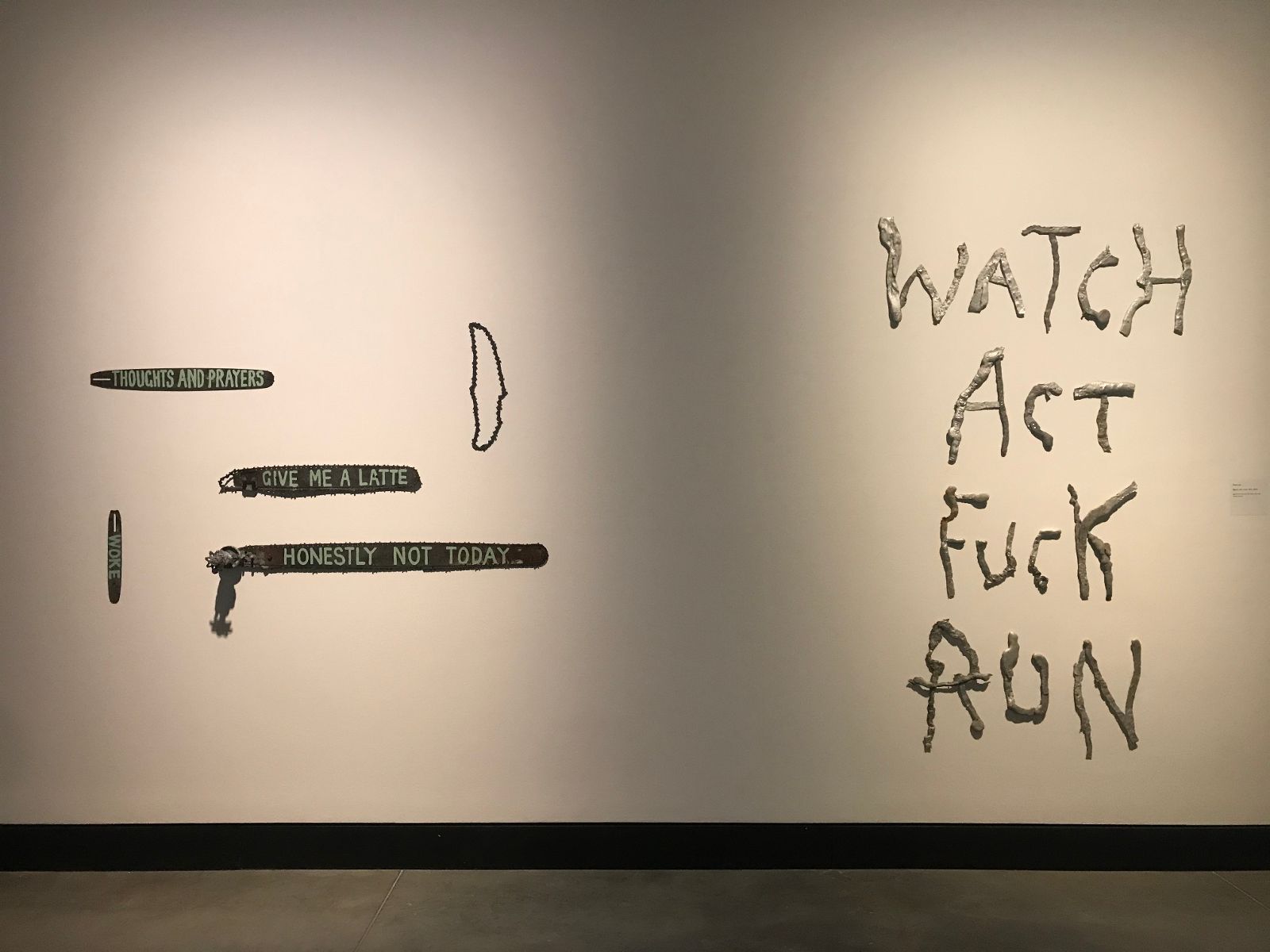

Five of Lee’s six works are crafted from the remnants of their house which stood on Biripi country at Warrawillah, an hour from the sea on the mid-north coast. In the most direct rebuke to consistent political brush-offs in fire-related media coverage, Now is Not the Time to Talk About Climate Change (2021) incorporates the skeleton of the chainsaw Lee and partner Aaron Crowe used to selectively harvest local timber for their low-footprint, hand-made home. But it’s the familiar script of rhetoric, and the old wedge between urban left (give me a latte) and the burning bush (thoughts and prayers), that gives the work its tension.

There’s a fine line being trod here, because Maitland is in the midst of coal heartland. Carbon Tax (2021) is composed of a wall-sized paste-up, a de-identified open-cut escarpment, one of the generic sublime black mountains that the Hunter does so well; in this setting, it is the stage for a three-part video sequence: the burning house (sparks beautiful like fireflies), the site eight months later (pathos), and Lee returning eighteen months later, to ‘weed wide enough to wrap a fairy in.’

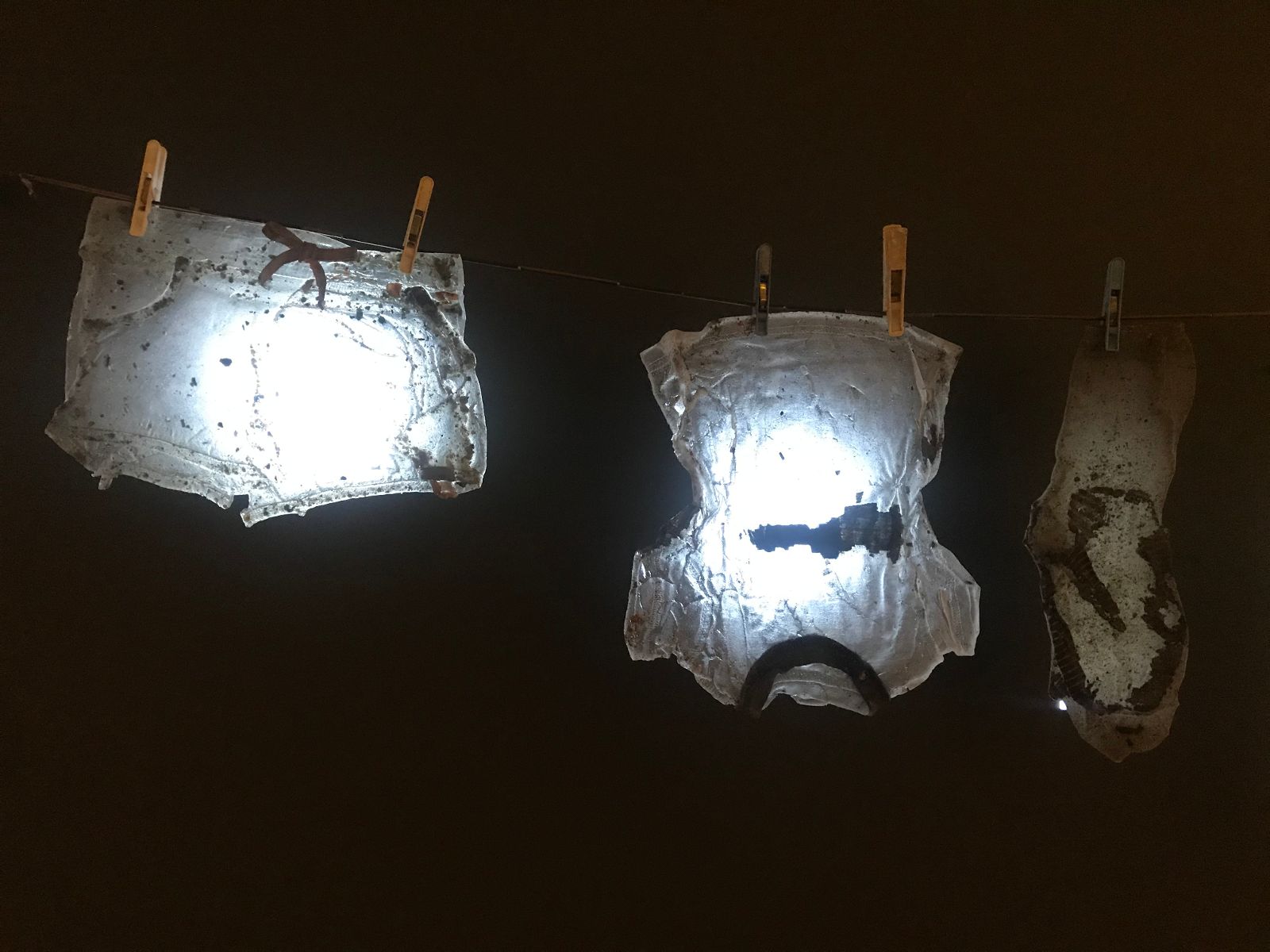

We might say they were lucky, leaving a few hours ahead of the fire front with their infant daughter, ‘…run through fire I will for thy sweet sake’. The Rural Fire Service messaging to leave early is rendered meaningless when the circumstances are as wildly unpredictable as they have become in recent summers, when clear communication, information and resources are so low on the ground. Watch. Act. Fuck. Run. (2020), constructed from the melted alloy bull-bar of a 1994 Toyota Hilux needs no interpretation. It’s the horror of the moment when hope and panic collide. By contrast, with more time to reflect, Abandoned, (2021) cast from epoxy resin, house ash and domestic remnants is the most poignant evidence of their ultimate fortune: the child’s clothing, back-lit against a black wall, spectral but also like prayer-flags of gratitude.

Unpreparable is not the first exhibition that Lee has derived from her family’s experience. Like the trauma of colonialism, it’s a perpetual cauterisation. Marking the fire’s first anniversary in November 2020, Manning Regional Art Gallery produced Packed Lost Found, documentary photographs by Julie Slavin and text by Tess Kerbel, drawn from local survivor’s accounts of the fires: how intention, loss and chance were memorialised in objects, and what mettle looked like. Such localised reparative responses were repeated across the country after the fires, from classrooms to art centres and community halls, creativity put to therapeutic, rather than industry’s service. Lee’s return to Newcastle following their loss, and to the coalface of her double calling, was further galvanised through support from the local arts community, including the MRAG artist’s bursary that generated this exhibition.[3]

The raw materials realised in concrete poetry and arte povera scripts are the indexical returns kept alight in Lee’s hands. While the embers on site were still smouldering, she carried out an action – and I don’t mean a performance – that bears retelling. Two days after losing every(material)thing, the family travelled to Sydney, dumping ash-rubble from their home onto the steps of the NSW Parliament. As if to demonstrate the causal link between fire and climate change, the act was also calling out an amendment to the State Environmental Planning Policy, which would unhitch climate change considerations from new coalmine and gasfield licences.[4] Lee is no island, and there’s no single nor direct causal link between her gesture and countless others, from Extinction Rebellion’s heat-on strategies, to First Nations' authorities on land and fire management and mobile agit-prop interventions.

Bushfire Brandalism | Various Artists is of the latter form, and it rips through the political bombast and national denialism with tragi-comic swag. What’s on display at MRAG (and a well-chosen companion to Lee’s show) are sixteen of a series of 41 large scale posters created by 78 artists. #BushfireBrandalism was an Australian summer project with the international Brandalism collective, a guerrilla campaign launched on 30 January 2020 by artist-activists in Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane. Invisible in high-vis with bespoke toolkits, artists replaced bus-stop ads with satirical paste-ups targeting the government’s mishandling of the fires and their then-spectacular climate denialism. The posters were quickly vandalised or cleaned up by civic servants, but they live on across virtual panoramas. At MRAG, the selection loses some of its subversiveness – the unsanctioned, sanctioned, the action valorised – but the full-colour spreads are a penetrating reminder to the public of nature’s claims (as well as human stakes) for protection and survival. The Brandalism manifesto puts it in more Shakespearean terms:

So imagine, if you will, another world/Emptied of mad empires/Manufactured fears/Paranoid dreams/and marauded [sic] lands/Now imagine the sounds of those memories/crushing in your hands.[5]

By now, it’s easy to imagine the worst. What is harder to believe, and yet wishful, are the changing conversations on the wind.

Footnotes

- ^ This and subsequent quotes, unless otherwise cited, are from Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, first printed in 1600.

- ^ Parliament of Australia Quick Guides 12 March 2020.https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/pubs/rp/rp1920/Quick_Guides/AustralianBushfires, accessed 16 October 2021.

- ^ Fiona Lee was awarded the Creator Incubator Fire Affected Artists Residency and the Graham Wilson Studio Residency in 2020.

- ^ Tess Kerbel, Packed Lost Found: Personal stories of the November 2019 bushfires in the MidCoast region. (Taree: Manning Regional Art Gallery, 2020), 27.

- ^ See the full manifesto here: http://brandalism.ch/manifesto/