Situated between sand dunes, a gently flowing river and a main road, the neat colonial facade of Sauerbier House is a reminder of South Australia’s settler past. Built in 1897 on the lands of the Kaurna people and located alongside the Onkaparinga/Ngangkiparingga (‘place of the river’), a sense of stillness and reverie remains with the house.

Though converted to a gallery and studios in 2015, a presence of its former life as a private residence and home endures. It exists now as a threshold between the private and the public, where remnants of the original house—fireplaces, arches, walls, ceilings—are often integrated into a lively program of temporary installations by contemporary artists.

In the exhibition FIELD NOTES, curated by the editors of fine print magazine Rayleen Forester and Joanna Kitto, the house and its site become integral to the display and reading of works by four Australian and international artists. The curatorial intention of FIELD NOTES is to explore:

the power of language and text—both written and spoken—in the creation and circulation of ideas and connections, in the preservation of tradition and memory, in truth-telling, and allowing us to see things as they are anew.[1]

To interrogate and extend these themes, an opening afternoon symposium was held at Sauerbier House, featuring two of the exhibiting artists—Léuli Eshrāghi and Grace Marlow—with invited speakers. Situated on the generous verandah and spilling into the garden, the five sessions featured discussion, readings, and a sound response by Alycia Bennett and Florian Cinco. The relaxed environment—a sunny day with the sound of birds and breeze through the gum trees—was a reminder that meetings and gatherings have been taking place on this land for many thousands of years.

Ali Gumillya Baker from the Unbound Collective provided a powerful perspective and historical context, saying:

Anthropologists go out with their diaries and make field notes on Indigenous cultures, but these record the evidence left of crime. This is a process of covering up. It is the attempted erasure and appropriation of the incredibly magical and beautiful and sacred places by a settler colonialism that seeks to possess, interrogate and own what our family and elders and community have always known to be the un-ownable.

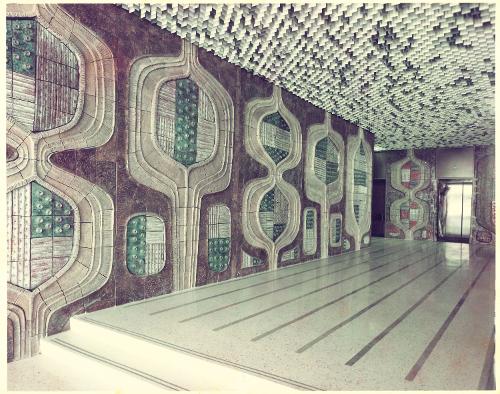

On this site in Port Noarlunga (a fishing place) located along the Tjilbruke Dreaming Track on the edge of the women’s river, these appropriations are in constant focus. Through the transformation of the house into a public space for discussion and community, there is a slow reckoning of colonial past to a newly imagined future. In FIELD NOTES, the house itself becomes a text, with works installed across the lounge room, hallway and wash house speaking to history, archive and truth-telling.

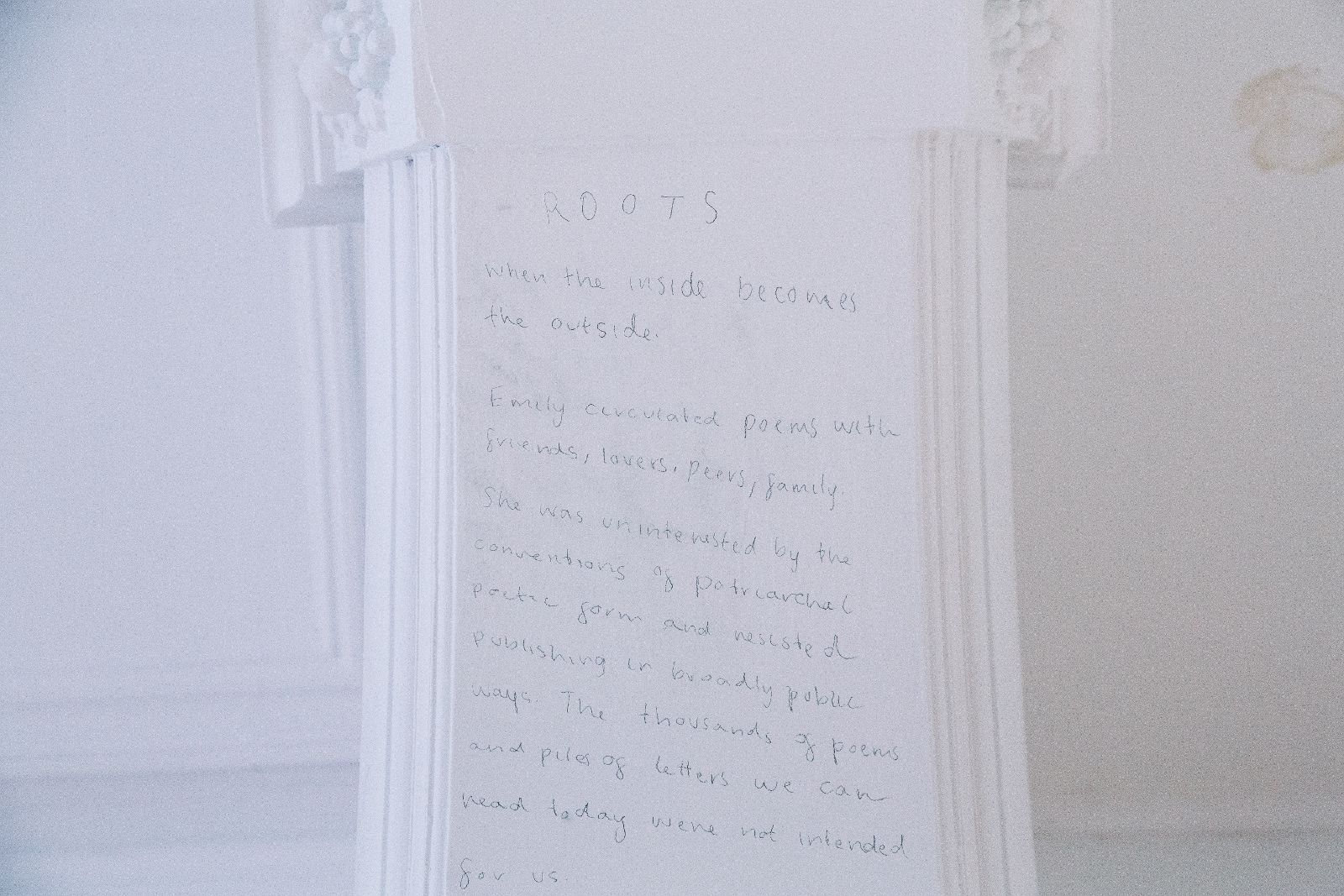

In Desire Archive (2021), Grace Marlow creates an intimate connection across two former homes on opposite sides of the world. The starting point is a white oak tree on the grounds of American poet Emily Dickinson’s home in Amherst, Massachusetts, and, in particular, a photograph taken during Marlow’s visit to the site in 2019.

The work is placed in the hallway, with two images of the tree mounted and pinned to ply leaning against the wall. The larger photograph shows the majestic scale of the oak tree itself (possibly planted by Dickinson’s brother, Austin). Leaning against this photograph is a smaller photo of Marlow’s hand touching the tree, with Dickinson’s house in the background.

Like Sauerbier House, the Amherst house is now a gallery and museum open to the public, displaying the artefacts and archive of Dickinson’s life and work. In a connecting gesture between the two former homes, Marlow inscribes lines of text in faint lead pencil across the white walls of the hallway. These are lines from emails composed by Marlow but written on the walls as fragments of memory. The writing is in places blurred and lightly scrubbed out, making the reading patchy and uneven. These lines evoke the process of Marlow remembering her visit to the house, of recalling incidents in small details or the re-telling of an informal encounter which has since taken on increased meaning.

Acting as the hallway entry point to the exhibition, Desire Archive brings themes of memory, personal stories, poetry and archive into focus, embedding the process of writing throughout the exhibition.

Past the hallway is the lounge room gallery featuring works by Delhi-based Raqs Media Collective and Sāmoan/Persian/Cantonese artist Léuli Eshrāghi. Raqs Media Collective are well known internationally for their installations that deal with time, language, urban research, and public and private life. It is a rare pleasure to see the work of this renowned collective in South Australia, and their video Time Flowers, Desire Seeds (2019), from the series Dohas for Doha, is a meditation on the continuum of time. Presented on a single monitor, the screen is free-standing and seems to float lightly against a white wall. It appears like an electronic page, shimmering and moving with an incandescent blue and green effect created from spectrographic analysis of a photographic image. Arabic and English text scrolls across this flickering videoscape, displaying proverbs and lines inspired by the Hindi poet and mystic Kabir. As the words fade in and out of focus and readability, it seems that the text itself is not meant to be read as a linear narrative. The use of English and Arabic combines to create a constant interchanging movement of language. The fragmented, singular words could be interpreted or read as fleeting glyphs and shapes, stripped of meaning and utilised as a rhythmic pattern to mimic the incessant flow of time and desire. Like Marlow’s wall writings, the text becomes form and pattern, inviting a gentle and immersive reading that resists conclusive narrative.

In close proximity to Raqs Media Collective in the relatively small lounge room is Léuli Eshrāghi’s Expanses (2021). The installation comprises two photographs of significant Arrernte places west of Alice Springs, hung on either side of a large-scale inkjet print on canvas. This fleshy pink canvas is suspended from the wall at one end by gold chains and then spills onto the floor like a wave, with remnant gold chain still attached to the other end.

Printed on the canvas is a poetic text by Eshrāghi which references their connection to sea, land, country and kin. It seeks to summon the life-force contained in the accompanying images and the sacred landscape of Mparntwe (where Alice Springs is situated). Surrounding the poetic text, which is written in English, the two short words TŪ and TĀ are scattered around the canvas, like a floating tempo, marking time and flow. It is only on hearing Eshrāghi reading the text on the accompanying exhibition website[2] that the beauty and power of TŪ and TĀ come to life as alliterative talismans. It was unfortunate that this reading wasn’t available to listen to in the exhibition, as the voice of the artist brought the work to life.

The neon work by Elyas Alavi, Doesn’t it taste of blood? (2020), is placed in the wash house, situated at the side of the house in the garden. This old red brick structure is often used as an annex to exhibitions and creates a significant contrast to the pristine white interiors of the house. Now based in South Australia, Afghanistan-born Alavi is an artist and curator who focusses his practice on the migrant experience and giving voice to refugees and the dispossessed. Early in 2020, he found a line from one of his poems painted on streets across Tehran, picked up by the community as a rallying cry. Translated from Farsi to English it reads:

As you draw water from a well

and make tea with that water,

doesn't it taste of blood?

This illuminated text sits on the ground of the wash house against a rough dark wall. Simple yet powerful, the artist suggests the appropriation of the words as graffiti, hastily scrawled on city streets, walls and fences. What the viewer experiences in the wash house as a bright pink sign is in fact a public act of defiance – a rallying cry from an artist and writer whose books have been banned by the Iranian government.

It seems uncanny that this small act of defiance makes its way to a seaside town south of Adelaide. Yet here it is, alongside the work of three other artists who work with text as a transformative act to cross the boundaries of public and private, of meditation and action, of the past and the present.

An exhibition curated by editors of a magazine, FIELD NOTES is firmly situated in an exploration of text, archive and language. It pays homage to the written word and the power of text as visual symbol, metaphor and image. It is a multi-layered and nuanced approach that is expressed through the fleetingness of time, the impermanence of memory and the journey to a decolonised future.

Footnotes

- ^ Rayleen Forester and Joanna Kitto, ‘An Introduction to FIELD NOTES’, http://www.fineprintmagazine.com/field-notes#/field-notes-introduction. Accessed 12 July 2021.

- ^ Léuli Eshrāghi, ‘Expanses’, http://www.fineprintmagazine.com/field-notes#/expanses. Accessed 13 July 2021.