.jpg)

Know My Name opened during COVID-19 in the wake of the effective #MeToo movement inspired by the testimony of Chanel Miller, in which she began: “You don’t know me, but you’ve been inside me...” In court, Miller was anonymously known as Emily Doe. Her book and the movement she inspired asked women to tell their stories and to speak their name [1]

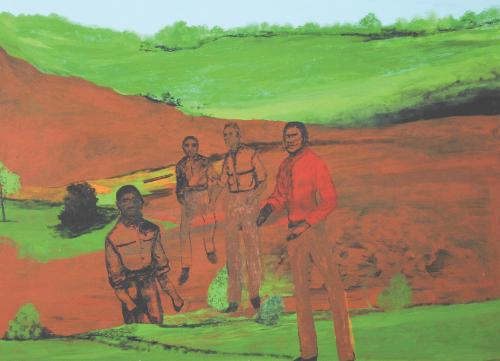

In one of the largest exhibitions of its kind in Australia, Know My Name exhibits works by more than 150 artists in order to “celebrate all women”. [2] Many of the artworks on display are drawn from the National Gallery of Australia collection, but plenty have been borrowed from elsewhere, underlining the paucity of women’s art in our national storehouse. Know My Name also includes commissioned exhibitions at the gallery, [3] images of works from the collection on billboards nationwide and signs imbedded in urban and regional communities, and an online conference. It is a grand statement, accompanied by a large catalogue with double-page spreads showing the artists’ works accompanied by short commissioned essays. The catalogue is the material document that cements the exhibition in art history. It is the text that will represent the exhibition for decades. It tells the story of women’s art in Australia from our principal gallery and will be cited by historians and scholars. As such, it needs analysis.

There are two short essays by the curators – Deborah Hart and Elspeth Pitt – and essays on the commissioned exhibitions, but there are no independent art historical or critical essays to contextualise the exhibition. One of the aims of the exhibition is to redress the under-representation of women artists in the collection (currently only 25% in Australian art, rising to 33% in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander art collection).[4] A manifesto-like statement of the eight guiding principles of the Gender Parity Action Plan adopted by the NGA is published in the catalogue.[5] The first principle is to “achieve equity across all activities including collection development and artistic programs on site, online and on tour”, while the remaining principles are more about staff development and processes.[6]

Although this first “principle” may address equity, as a strategy it falls short of signing up for affirmative action, which means we are beholden to unlegislated promises. This is in contrast to Spain where, in response to feminist lobbies, an act of parliament ratified in 2007 states that “all Spanish government structures responsible for the production and management of Spanish culture must ensure gender equity among exhibiting artists, advisory groups, and decision-makers, and they must be pro-active in supporting women artists to fulfil their potential”.[7] Although one critic has noted that Know My Name “is the most serious mea culpa made by a major gallery in Australia”,[8] in the wake of #MeToo, and the plight of Australia’s First Nations people, the public understands, with heavy hearts, that apologies don’t mean much.

.jpg)

Deborah Hart says that the exhibition “seeks to retell the dynamics of Australian art through the work of women to find new meanings and possibilities”.[9] She continues by outlining aspects from selected artists’ lives that demonstrate little-known connections across generations, and influences that have not been pursued elsewhere. Elspeth Pitt takes a similar approach, saying that “the project aims to enrich the linear, male-dominated narratives we’ve traditionally known”.[10] However, both curators employ conventional art historical approaches in their style of biography. It is interesting to note, for example, that Margaret Worth was taught by Dora Chapman, who Pitt claims may have been more influential on her style than her teacher and later husband Sydney Ball, but this doesn’t really capture for the reader/viewer the power of Worth’s bold modernism and her important contribution to that period.

There has always been a tussle inside feminist art history about the western canon, connected to the equity issue for women artists and their representation in exhibitions and collections. From the start of the Women’s Art Movements in the 1970s, the question has been debated whether women should aspire to enter the mainstream canon or resist it and take a political position outside that arena. Most women who were practising artists at that time wanted more visibility and to be acknowledged and included in the canon. Although radical resistance is more sustainable today, it is still extremely difficult to maintain a long-term art practice without some form of institutional support or recognition.

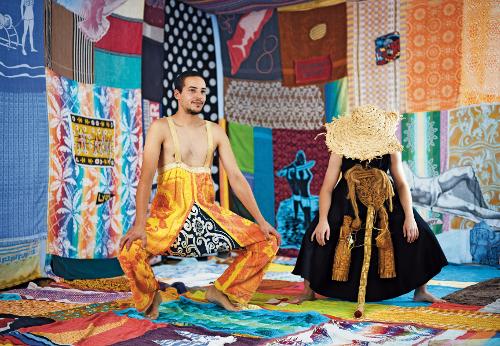

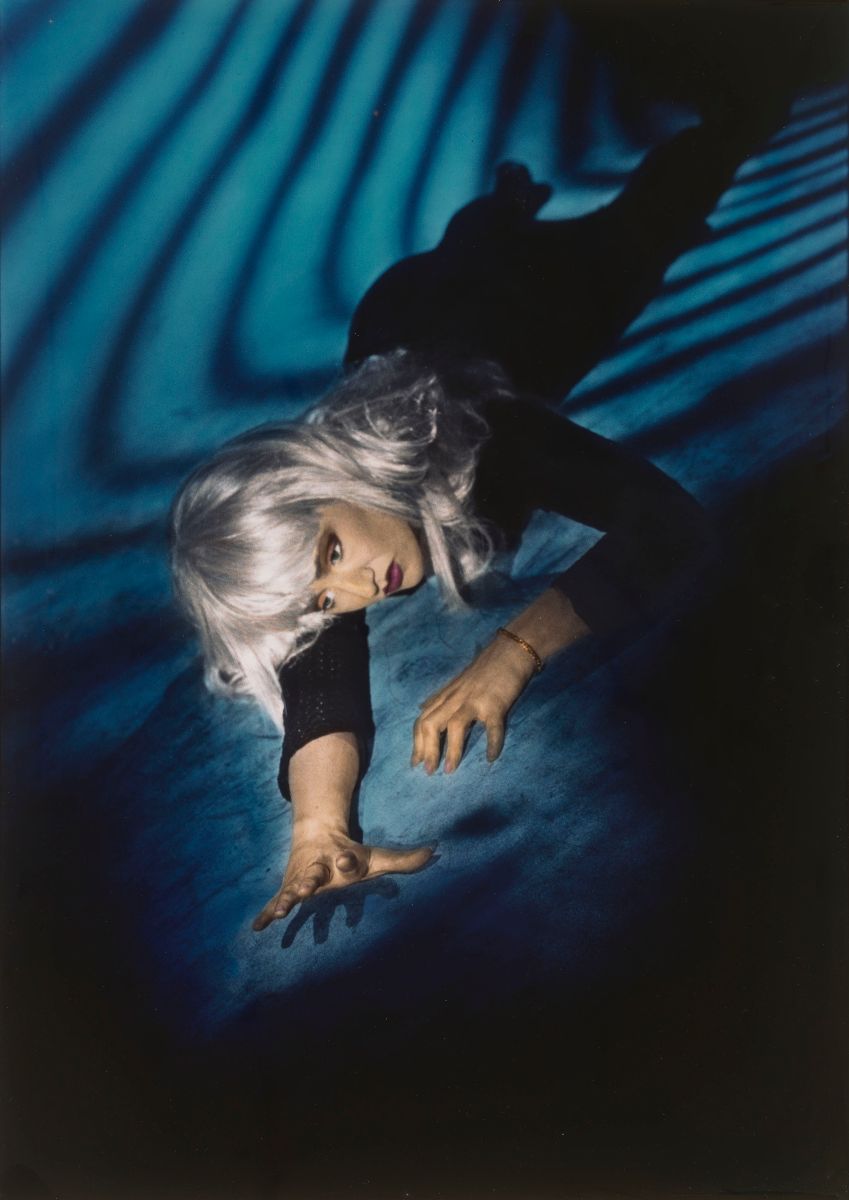

Know My Name is a lavish and multi-layered show. The exhibition is pitched to a wide audience that may be unfamiliar with women’s art. At this level it’s a pedagogical project and a memorial to the women who may have been forgotten. The feminism in Know My Name was mostly apparent in the online conference and the performative works that accompanied the program and the opening ceremony.[11] Hart says that “an important aspect of the exhibition is the role of performance as a vital artform in its own right in women’s practice”.[12] But Pitt explains that performance and ephemeral art are not collected by galleries because there are no designated departments to organise acquisitions. She says:

The frameworks and collecting policies of state and national galleries ... tacitly rely on the accrual of objects by curatorial departments arranged by media (painting, sculpture, photographs, drawings, prints) ... [this means that] performative art has rarely been acquired in depth or at all.[13]

The performative has certainly been celebrated in the mainstream curatorial scene since the 1980s when postmodernism took hold. This has resulted in the canonisation of performative and directorial photography and video performance.[14] But the genesis of these new genres is undoubtedly in the performance art of the 1970s and ’80s and the documentation of those artworks. The same can be said regarding collaborative and participatory practices that dominated the international biennale sector from the late 1990s under the name of relational aesthetics.

What needs to be added here is that women artists’ contribution to the experimental practices that followed the male and pale avant-garde of the 1970s has been undervalued and the Know My Name catalogue actually reaffirms this.

The argument that performance art is difficult to collect is a furphy, as the NGA has often shown video documentation of performance art. Mike Parr’s exhibition Language and Chaos, curated by Roger Butler and Pitt in 2016, was a major retrospective, with clear curatorial depth, showcasing Parr’s work in performance, video, film, drawing, painting and sculpture. Clearly the NGA understands the importance of performance art as a key indicator of experimentation over at least three decades, yet sidelines this in the context of Know My Name. Surely such a “celebration of women” needs to be flagged in terms of its strengths for art and cultural history.

Historical context

In many respects, Know My Name is a belated response to the surge of interest in women’s art and feminism that gained institutional momentum after the publication of Helen Reckitt and Peggy Phelan’s book Art and Feminism (2001) and the subsequent swelling of exhibitions in mainstream exhibitions such as WACK! Art and the Feminist Revolution presented by the Museum of Contemporary Art (Los Angeles, 2007) and Global Feminisms: New Directions in Contemporary Art (New York, 2007). [15]

In 1997, the Art Gallery of Western Australia hosted the first international women’s art blockbuster in Australia with the touring exhibition Inside the Visible: An Elliptical Traverse of 20th Century Art, in, of and from the feminine.[16] By this time women’s art and feminist criticism was long established in Australia. The Dissonance project coordinated by Artspace (Sydney, 1991) featured more than 70 independent events across art spaces, museums and universities, including Frames of Reference, a milestone for feminist exhibitions at the time.[17] Catriona Moore subsequently published her associated anthology Dissonance: Feminism and the Arts 1970–90, which became an important overview of feminist positions at the time.[18] In 1995, Joan Kerr’s National Women’s Art Exhibition, part of the National Women’s Art Project (1993–99), spawned a multitude of independent shows nationwide and resulted in significant publications.[19] Add to this an array of women’s art festivals, themed shows and feminist art exhibitions, and the extent of the field expands significantly. These exhibitions and the published research that they generated demonstrate complexity and together they represent the life blood of women’s art and feminist criticism in Australia.

.jpg)

This arena of difference that is feminism has a long and deep history that is often forgotten in the art world, where exhibitions tend to be locked into a contemporality driven by fashion in art and politics (policy). In many respects the exhibitions we see today are modernist by design. This may not be good curatorial practice for women’s art and feminist criticism. The inclusive First Australian Exhibition of Women’s Work in 1907 could well be a better model for a women’s art extravaganza underpinned by feminist theory. In fact, if we look at The Women’s Show of 1977 – curated by the Women’s Art Movement in Adelaide, a collective of more than 50 women – we see a similar commitment to inclusion across the arts. The exhibition was unselected, so that every woman who submitted work was programmed into an event. This feminist model of curating seems to take its cue from 1907.

The Women’s Art Festival in Sydney in 1983, which hosted a variety of women’s shows across the arts, was driven by a similarly utopian curatorial premise. It gave rise to a host of exhibitions, including the landmark Women Artists: Indonesia, Australia, Papua New Guinea at the National Museum of Australia, which showcased ceremonial objects created by Warlpiri women from the Yuendumu Women’s Museum in central Australia.[20] The Aboriginal Women’s Exhibition, curated by Hetti Perkins for the Art Gallery of NSW in 1991, also included a wide range of genres across a broad spectrum. It was the first major exhibition in a state gallery to champion the achievements of Indigenous women. In many of these exhibitions, a feminist proposition drives the curatorial practice through a methodology of inclusion and celebration. Although some of these events in Adelaide and Sydney did include specific feminist art exhibitions, they were part of a wider program that showcased women’s art more generally.

When one starts to look at alternative art spaces, activist-led exhibitions and contemporary galleries such as Artspace, the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, the Institute of Modern Art and the Australian Experimental Art Foundation, the field expands into the ultra-contemporary, the radical and experimental. If we add to this the work of private-sector galleries and museums that are responsible for a plethora of solo shows by emerging and mid-late career female artists, the scope of women’s art expands further. In 2021 it is impossible to ignore the enormous contribution that women artists have made.

Julie%20Rrap.jpg)

Despite this huge wave of women’s art in a multitude of contexts, to the best of my knowledge there have been only three survey exhibitions of women’s art in Australia’s national and state galleries in the past 10 years: Contemporary Australia: Women (QAG/GOMA, 2012), Who’s Afraid of Colour? (NGV, 2016–17) and Know My Name (NGA, 2020–21). The National Museum (NMA) has done better over the decades, most recently with Songlines: Tracking the Seven Sisters (2017–18), which presents a milestone for curatorial practice. With its executive curatorium guiding all aspects of the exhibition, the NMA sets a new benchmark for the other large galleries. Judith Ryan’s Who’s Afraid of Colour?, primarily a collection show, was magnificent in its scope but lacked support from the gallery to publish a substantial catalogue. In an online statement, Ryan said the exhibition looked at “great women innovators – transformers of tradition and precedent”[21] and included major female artists from both city and bush studios. Like Julie Ewington’s Contemporary Australia: Women, it championed the achievements of women. Ewington argues that women have broadened the scope and “reshaped the landscape of contemporary art”, and goes on to say:

The post-Kantian detachment once thought crucial to art has been comprehensively challenged, to be displaced, fractured and extended by a far more diverse, multifocal and, necessarily, robustly contested set of artistic expressions.[22]

In 1995 Victoria Lynn curated Review: Works by Women from the Permanent Collection, which showed 300 works by more than 80 artists, from the Australian collections at the Art Gallery of NSW. Once again, the curatorial approach was inclusive and encompassed textiles, ceramics and metalwork alongside paintings, sculpture, photography and prints. There were rooms devoted to early 20th-century artists such as Thea Proctor, Margaret Preston and Grace Cossington Smith. Although the focus was historical, Lynn also included major contemporary works by Emily Kame Kngwarreye, Fiona Hall, Ann Thomson and others. In 1995 Review was the largest historical exhibition of women artists from a permanent collection in Australia.[23] The earliest historical survey, Australian Women Artists, One Hundred Years: 1840–1940, curated by Janine Burke, was held at the Ewing and George Paton Galleries at the University of Melbourne for International Women’s Day in 1975.

Smaller exhibitions in university galleries and flagship art venues specifically addressed feminist art and criticism, such as the controversial Feminism Never Happened (IMA, 2010), A Different Temporality: Aspects of Australian Feminist Art Practice 1975–1985 (MUMA, 2011), which looked at ephemeral and performative aspects of women’s art, and Unfinished Business: Perspectives on Art and Feminism (ACCA, 2017–18), a contemporary survey curated by ACCA staff and a dedicated curatorium that enabled an informed critical selection of Indigenous works and art by women of colour.[24]

Given the remarkable history of women’s art and feminist criticism in Australia, it is almost criminal that our national collection needs to be attended to in the 21st century. The gaps in the collection are clearly visible by the amount of works that needed to be borrowed to present the show. This suggests that key works have been snapped up by other galleries and collectors. It is also surprising, given the history outlined here, that the NGA chose not to position its collection in relation to the critical positions. The associated conference went some way to addressing feminist critiques of contemporary culture, but it tended to speak almost exclusively to the barrage of identity politics that has swept the western world in the past few decades without contextualising these issues within the more complex debates that have engaged feminist and postcolonial thinkers during the same timeframe. Most disappointing was that the exhibition catalogue did not take the opportunity to strongly outline the enormous influence that women’s art has had on art and society and the ways in which movements in women’s art have challenged and changed the cultural landscape both in Australia and internationally. Women artists have led a revolution in cultural change, they have pioneered new avenues of experimentation and, through a plethora of different performative practices, they have expanded the field of visual culture outside the museum. This needs to be acknowledged.

Footnotes

- ^ Miller’s raw and emotive testimony was first released on social media in June 2016. It was read by 11 million people in four days. See Leigh Gilmore, ‘Chanel Miller and the New Power of Women’s Words’, Cognoscenti, 17 September 2019: https://www.wbur.org/cognoscenti/2019/09/17/brock-turner-she-said-me-too-leigh-gilmore (accessed 15 January 2021). See also Chanel Miller, Know My Name: A Memoir, New York: Viking Press, 2019.

- ^ Nick Mitzevich and Natasha Bullock, ‘Forward’, Know My Name, Canberra: National Gallery of Australia, 2020, p. 19.

- ^ Commissioned installations and theme-style exhibits include works by Patricia Piccinini, the Tjanpi Desert Weavers and Angelica Mesiti, a photo-based show focusing on sex and sexuality and a VR animation installation by Jess Johnson and Simon Ward.

- ^ ‘About Know My Name’, NGA website: https://knowmyname.nga.gov.au/about/

- ^ ‘Guiding Principles for Gender Equity’, Know My Name, pp. 22–23. The project was also driven by an agenda of enabling, with the institution pledging to listen to the excluded, especially the hearing and visually impaired and the physically disabled. This was a strong political agenda during the four-day conference and is reiterated on online materials.

- ^ ‘Guiding Principles for Gender Equity’, Know My Name, p. 22.

- ^ See Hilary Robinson, ‘Feminism Meets the Big Exhibition: Museum Survey Shows since 2005’, Curating in Feminist Thought, Issue 29, May 2016, p. 34.

- ^ Jenna Price, ‘Know My Name: Tokenism or a genuine sign of change for female artists?’, Sydney Morning Herald, 13 November 2020: https://www.smh.com.au/culture/art-and-design/know-my-name-tokenism-or-a-genuine-sign-of-change-for-female-artists-20201105-p56bzk.html

- ^ Deborah Hart, ‘Know My Name: Australian Women Artists 1900 to Now’, in Know My Name, p. 385.

- ^ Elspeth Pitt, ‘I Remember, They Remember, We Remember’, in Know My Name, p. 393.

- ^ The conference and some of the performance works in the program will remain online until the end of the show.

- ^ Hart, ‘Know My Name’, p. 389.

- ^ Pitt, ‘I Remember’, p. 395.

- ^ See Anne Marsh, LOOK! Contemporary Australian Photography, South Yarra: Macmillan, 2010, and Performance Ritual Document, South Yarra: Macmillan, 2014.

- ^ See Helen Reckitt and Peggy Phelan (eds.), Art and Feminism, New York: Phaidon, 2001. Also see Lisa Gabrielle Mark (ed.), WACK! Art and the Feminist Revolution, Los Angeles: Museum of Contemporary Art and Cambridge, Massachusetts/London, England: The MIT Press, 2007. Maura Reilly and Linda Nochlin (eds.), Global Feminisms: New Directions in Contemporary Art, London and New York: Merrell Publishers, 2007. Other major exhibitions included Fusion Cuisine (Athens, 2002); It’s Time for Action (There’s No Option); About Feminism (Zurich 2006); Kiss Kiss Bang Bang: 45 Years of Art and Feminism (Spain, 2007); The International Incheon Women Artists’ Biennale (Korea 2007, 2009, 2011); and Elles@CentrePompidou (Paris, 2011), among others.

- ^ M. Catherine de Zegher (ed.), Inside the Visible: An Elliptical Traverse of 20th Century Art, in, of and from the feminine, Cambridge, Mass., and London, England: The MIT Press, 1996. The exhibition toured internationally after being first shown in Boston. See also: https://www.artlink.com.au/articles/373/an-elliptical-traverse/

- ^ Julie Ewington, ‘Frames of Reference’, Art & Text, 41, 1992, pp. 30–32 (reprinted in Anne Marsh, Doing Feminism: Women’s Art and Feminist Criticism in Australia, The Miegunyah Press/Melbourne University Publishing, 2021, forthcoming).

- ^ Catriona Moore (ed.), Dissonance: Feminism and the Arts 1970–90, St Leonards, NSW: Allen & Unwin in association with Artspace, 1994.

- ^ See Joan Kerr and Jo Holder (eds.), Past Present: The National Women’s Art Anthology, Sydney: Craftsman House, 1999.

- ^ Kate Khan, ‘COMA Women and Arts Festival October 1982: Warlpiri Women at the Australian Museum’, COMA: Bulletin of the Conference of Museum Anthropologists, Vol. 12, 1983, pp. 22–25. Scott Mitchell, ‘“To the city for dancing”: The Women Artists collection and the birth of commercial art practice at Yuendumu’, in A Cultural Cacophony: Museum Perspectives and Projects, (eds.) Andrew Simpson and Gina Hammond (online version, 2016), pp. 86–102: https://www.amaga.org.au/ma2015-sydney (reprinted in Anne Marsh, Doing Feminism).

- ^ ‘Who’s Afraid of Colour? Artwork labels’, NGV website: https://www.ngv.vic.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/WhosAfraidOfColour_ArtworkLabels.pdf

- ^ Julie Ewington, ‘Here and Now’, Contemporary Australia: Women, Brisbane: QAG/GOMA, 2012, p. 15.

- ^ See Victoria Lynn, ‘Review – The Australian Collection’ in Review: Works by Women from the Permanent Collection of the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney: Art Gallery of New South Wales, 1995, pp. 1–15.

- ^ In a literature search for women’s exhibition catalogues from 1974 to 2015, undertaken at the State Library of Victoria in 2016, I discovered 105 women-only exhibitions (1970s: 22, 1980s: 17, 1990s: 28, 2000s: 15, 2010–15: 23). This is by no means exhaustive, as smaller exhibitions outside Victoria were poorly represented, but it gives some indication of the scope of activity.