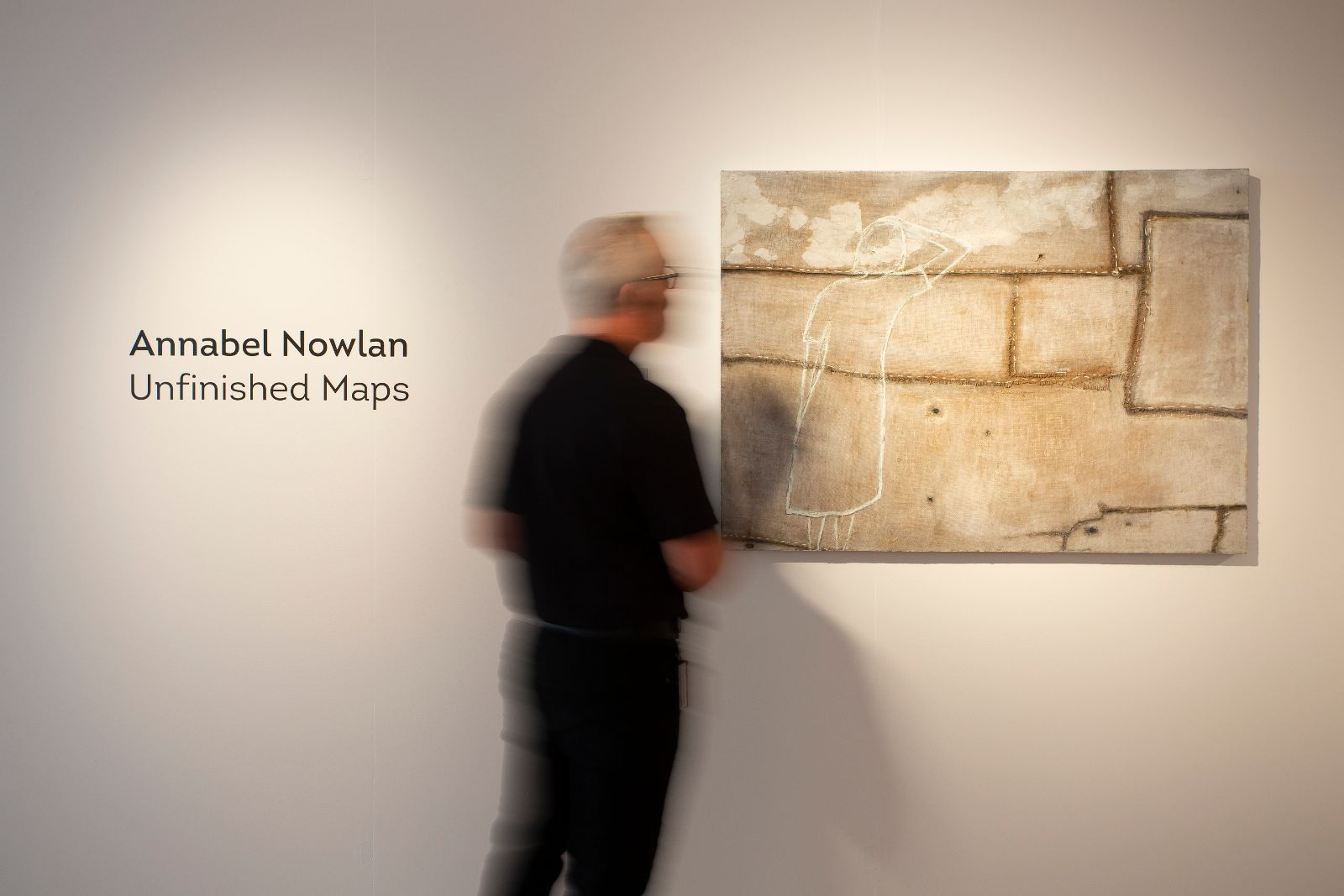

Annabel Nowlan’s Unfinished Maps reveals the findings of more than a decade of investigation into Australian landscapes, histories, mythologies and vernacular language. This is an ongoing excavation in which the artist shares artefacts and observations regarding her family’s history, the occupation of Indigenous country, and the historical forces that have shaped our understanding of it. These are evident through names, secret codes and symbols, literary references and the repurposing of scavenged materials.

The exhibition first appears as a shimmering survey of scuffed aluminium, with nine-part grids and other objects rusted to an alluring turquoise patina. At the entrance, a weathered timber fence post holds aloft a smooth stone. Someone stood here before you, and wanted you to know it. This anonymous statement, like a cairn of stacked stones, apparently is a swagman’s secret code for a welcoming place.

This marker is the first symbol in a series of introductions to one of the lost languages of the swagmen. The stories and artefacts of regional Australian swagmen – be they jolly campers by a billabong or hard-working resilient itinerants – occupy an important space in Australian social history and popular mythology. These marginalised individuals, usually men, moved through other people’s occupied land. They lived spartan lives as disenfranchised labourers – “down on their luck”, as Frederick McCubbin showed us in 1889 – or otherwise seeking purpose in an unwelcoming climate. They walked alone along travelling stock routes and isolated roads. Songs and poems aside, the swagman’s legend is a hard-hewn narrative of homelessness.

Nowlan’s storytelling begins by acknowledging the space these wanderers occupy in our imaginations today. We begin with the epiphany of realising their relics remain, and they can be found and deciphered like obscure Australian hieroglyphs. This encourages us to consider the experiences of our own families or regional Australian histories as more than words strewn across a map. Through connections to her family’s farm in Bimbi, New South Wales, Nowlan invites found objects to serve as collaborators.

The wall of sculptures – Curios (2010–21) – reads like a wunderkammer of the antiquities of the outback, each one studiously jerry-rigged to get a job done. God knows what their job was, but against the odds, these votive offerings seem to have outlasted it. Nowlan’s metaphoric and physical practice of appliqué applies through all of these sculptures, layering stories through materials, titles and the interaction of forms.

The depth of Nowlan’s creative research is obvious, as this exhibition includes work developed over ten years, culminating in her sculptural and text-informed works of 2020. Of these, swagmen’s glyphs form a vital part of her Swaggie Symbols 1–8 (2020) and Genius Loci 1–9 and 10–18 (2015–20), as well as the manifesto-like culmination of New scars I and II and Old scars I and II (2020). In this final diptych, we see different languages, beyond the names of the First Nations. A cluster of signs and symbols that look like urgent hieroglyphs are quoted from the legend of a miner’s map at Hill End, marking all the subterranean incursions in the area.

But for those above ground, we heed warnings. “Here lives a man with a gun.” “Religious talk gets you a free meal.” “This town has a judge, a court and a jail.” “This is a good place, they serve alcohol.” Apparently there’s also a symbol for “A nice woman lives here”, but it does not appear here. Such blunt epitaphs, vernacular and evocative, provide facts as advice.

Nowlan has been known to surreptitiously leave these subtle symbols in places she travels. One hopes that this could promote others to adopt this secretive street art, leaving curious codes like those once used to access wi-fi networks (known as ”warchalking”). But as any semiotician worth their salt will tell you, it takes knowledge of both the signified and the signifier for the sign to have any meaning. Swaggies’ symbols are a forgotten visual language, and it is time we restored them.

After these silvery scratched signals, we find other works bearing a rich, rusted copper patina. These green surfaces, which appear throughout Unfinished Maps, allude to the temperature and humidity of the atmosphere – darker on damp days, brighter in the sunshine – as well as a familiar shade of paint popular in the early 20th century: l’eau du Nil, the water of the Nile. Now associated with art deco interior design, this cool pale green conveys nostalgia when new, but a long lifespan of deterioration when decrepit. It’s not the actual colour of the Nile (for the most part, like the Murrumbidgee or the Murray, it’s a big brown river), but it speaks to the decades of the early 20th century when Australian soldiers returned from Egypt to establish soldier settlements, receiving farmland allotments as a reward for service in the First World War. As Nowlan inscribes their struggle, “They gave him an axe, a billy can and an adze”, and the rest is history.

These historical connections move beyond evocative colours. Nowlan’s storytelling extracts poetic samples from understated biographies and letters. The intricate listing of farm objects at a Clearing Sale (2010) features solid metal slowly yielding to the forceful engraving of each word, like a hesitant speaker reading aloud. Loaded Dog is a dented orb of verdigris, in which a long and lingering fuse evokes Henry Lawson’s folkloric story of 1901 – a story, like Gundagai’s dog on the tuckerbox, which did not end well for the dog. Collections of slang Australian phrases – specifically those of New South Wales and Victoria – provide the goût de terroir, or flavour of the earth, just as a naturalist might record flora and fauna during a scientific survey.

Names are especially significant in Unfinished Maps. Lists of places, and birds, create an itinerary of a traveller’s path. These mark constellations across a map of New South Wales, including familiar and obscure sites, charting an eccentric path of personal significance to Nowlan. Similarly, lists of bird species discreetly imply their habitats, suggesting the landscape around her family’s farm at Bimbi. Nowlan is a birdwatcher and is fully aware of the significance of surveillance; she uses the silhouette of a chair as a symbol of power over the landscape. She describes her similar sculpture Top Dog as occupying the position of one who surveys the horizon. Through this power dynamic, we can also see the contestation between Indigenous words for the names of birds and the colonist’s imposed alternatives.

Within Nowlan’s Genius Loci series – the spirit of place – we find a voice who seems unexpected in a regional Australian landscape. Friedrich Nietzsche’s quote “It is certainty, not doubt, that causes madness” is legible on an inverted glass frame, close to the perforated netting of a Coolgardie safe and an hourglass of brass thumb tacks. It reminds me of René Descartes’ advice that “the first sign of wisdom is doubt”.

This “doubt” brings us back to the title. Unfinished Maps is unfinished because it is an ongoing conversation, sustained by Nowlan for more than a decade. This exhibition shows us that cartography is where geography and history meet in the political present. Through traces of mythic swagmen, found objects, collected words and observed birds, Nowlan builds a vision of regional Australia that is insightful, intricate and subtle.