Paul B. Preciado, one of the most astute interpreters of the biopolitics of COVID-19, lost sight in their left eye after catching the disease. Just as it can affect taste and smell, corona-related inflammation (caused either by the virus or the immune response of the host) can damage the retina and optical nerve and, certainly in Preciado’s case, lead to temporary blindness.[1]

Blindness, in its biological and ideological form, is one of the disease’s strongest figures. Giorgio Agamben, a fierce critic of the social and cultural implications of lockdown and of the biopolitical reduction of life in the face of the pandemic to “a purely biological condition”, sees blindness as intentional: “The first thing the wave of panic that has paralysed the country obviously shows is that our society no longer believes in anything but bare life … Bare life – and the danger of losing it – is not something that unites people, but blinds and separates them.”[2] “The gaze is absolutely pervasive,” but there is actually very little to see.[3]

The fact is we do struggle to see COVID-19. It’s respiratory and microbiological and unlike certain other pandemic diseases given visible form through a very specific sets of images – the rotting flesh of syphilis and leprosy; the dark skin patches of the bubonic plague and the AIDS-related Kaposi Sarcoma – it doesn’t appear to have a “visual boundary”.[4] The iconography of the disease – immunitarian (and now still, highly ideological) masks and the crosses and arrows that regulate social movement and spatial distancing – is not referentially biological, but biopolitical.

Biopolitics has colonised the language and images of biology and virology, and of feeling and affect.[5] Human relations have become “molecular”, and love and desire (and communal life) are no longer so much expressed through touch, merging bodies, or exchanging bodily fluids or breath, as through isolation and distance: “Today I display my love for the other by keeping him or her at a distance.”[6]

Bryan Foong is a painter whose intersecting practices – artistic, biological, medical, queer – have come to converge around the biopolitics of lockdown and the regime of molecular human and social bonds. The management of the pandemic has produced a quite specific politico-medical alliance,[7] and Foong is an active agent of, and witness to this project. At the same time as being subject to the regime of confinement and isolation that has affected most of us, Foong’s work has seen him travelling outside, among “the subaltern vertical workers” whose labour cannot be undertaken safely, remotely,[8] providing medical care to patients isolated in their homes.

His experience of this alliance informs the first iteration of an ongoing project examining the biopolitics of COVID-19, recently presented at the artist-run space ANCA in Kamberi/Canberra, just as bodies across the country were starting to physically reconnect. This exhibition presented what seemed at first a topographical account of Foong’s specific experience of shutdown, and of the terms of moving, touching and looking that were produced and demanded by it.

The installation, comprising paintings, text, projected image, sound and objects, all products or traces of processes of repetition, accumulation, erasure and recycling, engaged a highly iterative mode that qualified the experience of shutdown. Across these objects, multiple, seemingly disassociated narratives folded into one other, each in some way related to the biological phenomenon of capture myopathy, the profound cellular and organ dysfunction, malaise and atony affecting animals subjected to prolonged captivity.

Capture myopathy, represented in slides of histological details, a found photograph of a laboratory rat from a 1966 Time-Life publication and across surfaces and statements, provided a literal and metaphorical image of biological and social shutdown – of affective isolation and immunitarian and communal vulnerability. For example, three paintings presented as heavily scored grounds of layered paper and paint – surfaces literally worn down by the artist’s added and subtracted effects and marks (including spatial distancing crosses, directional arrows and text).

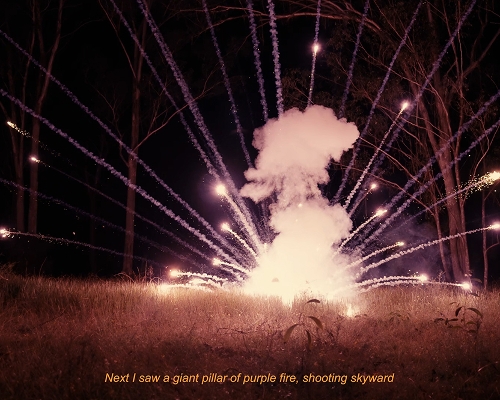

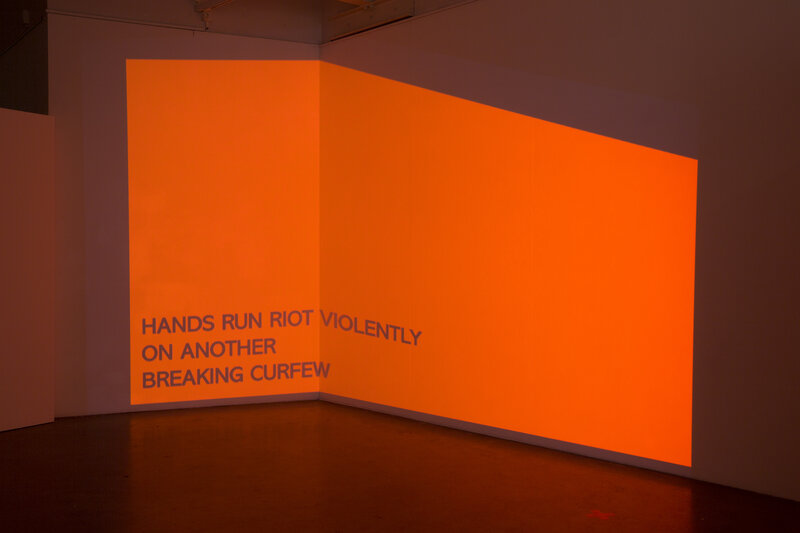

These surfaces and images were presented as at once abstract and, in the context of other images in the exhibition, iconographically “histological”. The paintings hung alongside a modified ladder that seemed a proxy for stalled progress, and masses of taped spatial-distancing markers that in their repetition and randomness assumed decorative rather than utilitarian associations. Each of these subjects and strategies (the denial of narrative or progression in favour of repetition and stasis) were reiterated in the single-channel video Hands are Burning, actually a Powerpoint slide show of images including microscopic details observed in capture myopathy, and declarative texts related to the medical, economic and bodily experience of the pandemic and shutdown. The slide show’s rudimentarily delivered information recalled the didactic, simplistic visual supports, homilies and slogans delivered by the state during the pandemic.

This presentation of text and image was supported by a sound component produced in collaboration with Warrang/Sydney-based artist California Girls. The track appropriated the elegiac yet reductive language and form of Michael Nyman’s “An Eye for Optical Theory” (itself a rearrangement of the 16-note bassline “Ground in C minor” attributed to William Croft via Henry Purcell) commissioned for Peter Greenaway’s 1982 film The Draughtsman’s Contract. The circulatory saxophone and bass rhythm of this Nyman/Croft (now Foong/California Girls) harmonic frame literally provided the repetitive ground over which the exhibition sat. Drawing explicitly as it did on Nyman’s reiterative, melancholic phrasing and repudiation of progressional narrative (no “hills, troughs, climaxes, purposes, goals”),[9] it worked to create what Foong describes as a “eulogy to the body”.

The allusion to disembodied looking in the title of Nyman’s track mirrors the detached perceptual field of Foong’s medical and biological practice. Many of the projected declarations directly invoked the artist’s medical labour and knowledge, drawing attention to the ways its gaze positions the body as an object of study, often in tacit support of political imperatives and social regulation. He is himself inscribed within this field of medicalised looking and social control: “model organisms”, “capture myopathy”, “resistance is a muscle”, “an exciting time for our genetic template”, “for your own good”.

All the same, I was interested in the way the soundtrack’s bassline became an undulating pulse, and it was here that the project moved from being simply “topographical” to become an act of recovery. The track provided diegetic sound for projected declarations related to bodily experience and touch in the time of the virus, and to Foong’s interrogation of the modes of subjectivity and sovereignty given shape through the political management of bodies.

The title of this work, Hands are Burning, alongside other statements related to touch, desire and sex, became a reference to queer bodies generating heat that, in the context of shutdown, appeared transgressive: “penumbra is my safe word”, “held down in position / if it hurts stop touching it”, “Hands run riot violently / on another / breaking curfew”.

I am not interested in the politics of compliance indicated in a statement like ‘Hands run riot violently / on another / breaking curfew’. This was simply an utterance, even if the effects of ‘violent’ touching were plain to see on the surfaces of paintings. But I am interested in the way the work underlined the normative attributes of touch, or how shutdown and its regulation – the neoliberal response to COVID-19 – made visible the ways that touch remains (or has become again) bound to a sexual sovereignty that is colonial, domesticated and patriarchal: on the one hand, the neoliberal dream of non-collectivisable bodies without skin (living and working remotely);[10] and on the other, desire and touch submitted to genealogical and parental affects and legacies – the body back to being primarily a site of production.

Think of how touch during shutdown is bound to linguistic and legal frameworks that are monogamous and classifiable, with travel to visit another in some jurisdictions only possible if the other is a designated partner. One of Foong’s declarations seemed to open the whole project up: “Another night sleeping with the law”, a statement that summons both abstinence and the law of the father. So what began as a topographical account of the biopolitical management of COVID-19 became for me an argument for a horizontal and porous culture of desire, and social relations that acknowledge touch as a creative act– in queer terms, touching the other as other, actively participating in our creation.

Further, it invoked touching as a representation of what Judith Butler describes in their appeal for a post-corona “intertwined” world-sharing in which, like breathing, touching signifies our vulnerability and “the interdependent character of our biological selves and our social selves”.[11] Both representationally and materially, this installation of works as painting, projected image, text and sound all reinforced this interdependency. Perhaps this haptic aspiration makes manifest a yearning for a radical displacement of sight. In its negotiation, we feel our way through the dense semiotics of the pandemic, away from this infectivity (this death) that we cannot see.

.jpg)

Footnotes

- ^ Paul B. Preciado and Jamieson Webster/Alison Gingeras, “Pathologically optimistic: a conversation with Paul B. Preciado”, Gagosian, Winter, 2020, pp. 74–79.

- ^ Giorgio Agamben, “Clarifications”, trans. Adam Kotsko, “An und für sich”, 17 March 2020.

- ^ Paul B. Preciado, “Learning from the virus”, Artforum, May/June 2020, p. 81.

- ^ Sander L. Gilman, “AIDS and syphilis: The iconography of disease”, October, no. 43, Winter, 1987, p. 90.

- ^ Judith Butler has noted the “life-taking figuration” of “the anthropomorphised health of the economy” in Judith Butler, “On COVID-19, the politics of non-violence, necropolitics, and social inequality”, 23 Jul 2020.

- ^ Sergio Benvenuto, “Forget about Agamben”, European Journal of Psychoanalysis, 20 Mar 2020.

- ^ On the politicisation of medicine and medicalisation of politics through COVID-19, see Robert Esposito, ‘The biopolitics of immunity in times of COVID-19: an interview with Robert Esposito’, Antipode Online, 16 June 2020.

- ^ 8 Paul B. Preciado, “Learning from the virus”, Artforum, May/June 2020, p. 84.

- ^ Michael Nyman and Larry Simon, “Music and film: an interview with Michael Nyman”, Millennium Film Journal 10‒11, Fall‒Winter 1981–82, p. 229.

- ^ Paul B. Preciado, ‘Learning from the virus’, p. 82

- ^ Judith Butler, “On COVID-19”; see also Luce Irigaray, “How to escape the dictatorship of Covid-19?”, European Journal of Psychoanalysis, 18 Sep 2020.