Strange to think of Gordon Bennett as an almost classical figure in contemporary Australian art. After years of critiquing art-historical standards, Bennett has himself become the standard bearer. Six years after his death at the age of 58, his practice represents a canon that future generations of artists will be both motivated and shadowed by. In this, his first homegrown retrospective at the Queensland Art Gallery of Modern Art (QAGOMA), some of Bennett’s most well-known series are framed by seriality itself. At the centre of Unfinished Business: The Art of Gordon Bennett – its beating heart – is a freestanding display of numerous works on paper, establishing how the Queensland-born artist obsessed over his ideas in multiple drawings, watercolours and revisions, in constant dialogue with his own visual vocabulary as much as he was with those whose works he appropriated.

After two previous travelling retrospectives – at the Brisbane City Gallery in 1999, and the National Gallery of Victoria (NGV) in 2007 – how should we think about Bennett today? In a preview of the 2007 NGV show, art historian Rex Butler called him “a great revolutionary,” claiming he transformed urban Aboriginal art to the more conceptually savvy postcolonial art; the second revolution within living memory in Australian art, after early-seventies Papunya.[1]

In 2020, Bennett still towers over those he inspires, perhaps even more so than in 2007. One of the few genuine masters of post-nineties art in this country, his work continues to mobilise others to contest the pernicious but once pervasive idea that only Aboriginal people living in remote communities possess a genuinely Aboriginal culture. For a stark indication of just how far we’ve come, take a look at Peter Schjeldahl’s 1988 review Paintings by Aborigines, which is peculiarly ignorant in a lucid kind of way, seeing the merit of Indigenous art only in its “power of strangeness.”[2] A recent publication, Gordon Bennett: Selected Writings (2020), by Griffith University Art Museum and Power Publications, testifies to Bennett’s intellectual struggle and perseverance, making public many of his unpublished writings, interviews and statements: blueprints for any Australian political artist in the future.

With a vaguely chronological touch, Unfinished Business is essentially the story of an artist who, in a deeply conservative city, worked through an identity crisis to become a key voice in the legitimisation of dissent for First Nations artists. Allusions in the show range from Søren Kierkegaard’s choices to Margaret Preston’s domestications; from Imants Tillers’ Eurocentrism to Ice-T’s post L.A.-riot anger. Bennett dances to the latter’s 1993 song “Race War” in the video work D.U.H! (Down under Homi) (1994), the title itself a summoning of Homer Simpson, hip hop slang and Homi Bhabha. Bennett not only references complex postcolonial and social justice issues within a vernacular frame, he immerses himself completely in them, with an intelligence, eloquence and vulnerability rarely before seen.

Born to a white, Anglo-Celtic father and a mother of Indigenous descent, Bennett, a natural teacher, understood that history manifests in us as pedagogy; the past walks, often uncomfortably, in our shoes. After graduating from the Queensland College of Art in 1988 at the age of thirty-three (amidst Bicentennial celebrations, and in the aftermath of the cold-blooded nineteen-year reign of Premier Joh Bjelke-Petersen), he achieved quick success with works that, to contemporary eyes, are probably too redolent of art school petitioning. It is from Possession Island (1991) onwards that he began to look more like the broad-horizon artist he became, bolstered, perhaps, by early-nineties attempts at Indigenous reconciliation, including, of course, the 1991 repeal of terra nullius in the Mabo case, and, the following year, Paul Keating’s 1992 Redfern Park address. With one eye on his own identity and one on the longue durée of history, his works exerted a worldly significance at a time when the term “global art” was beginning to look like it could be more than just a postmodern pipedream.

Against the often-touted opinion that Bennett is an angry and difficult artist, sophistication is all I see here. Like the bearded Van Gogh-like figure with his head above the water in Haptic Painting (Explorer: The Inland Sea) (1993), his works tend not to reveal the efforts going on underneath; the rigour necessary to keep it all afloat. Of course, maintaining this appearance was part of his brilliance. In reality, he surely felt like he was drowning at times, unable to meet public expectations of being a certified spokesperson for contemporary Aboriginal art. As early as 1989 he was saying: “My quick success has something to do with my Aboriginality and that worries me.”[3] By the end of the 2000s, he was leading a notoriously reclusive life in Samford Valley, on the outskirts of Brisbane, distant, at least physically, from the proppaNOW collective, the rise of Tony Albert, Archie Moore, Vernon Ah Kee and the quiet transformation of Indigenous art in Queensland that wouldn’t have occurred without him.

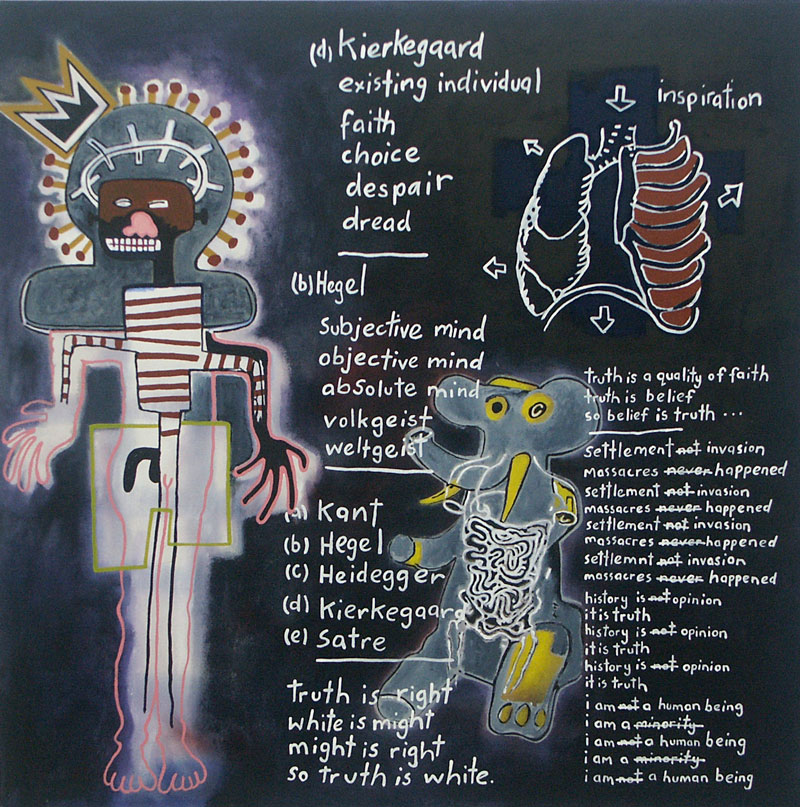

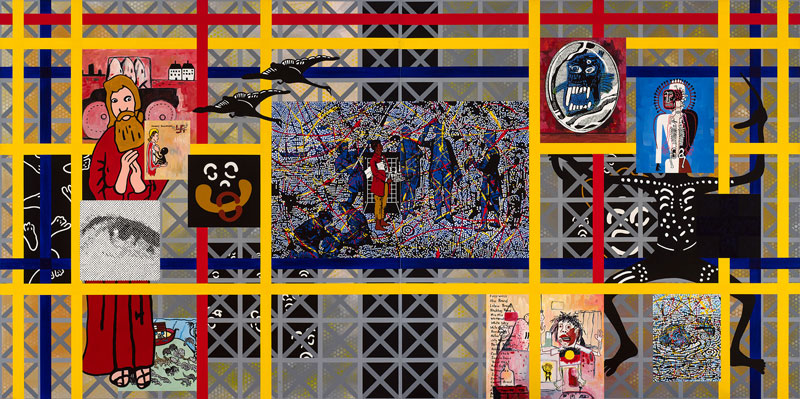

For QAGOMA curator Zara Stanhope, Bennett was an “intellectually restless artist”; so the focus, here, on his equally restless preparatory work makes a lot of sense.[4] It is something Bennett himself alluded to throughout his career, most notably in Notes to Basquiat, which is heavily represented in the exhibition. The watercolours and sketch works, such as After Basquiat (1993) and Always Impressed by Losers (1993), are highlights, revealing how Notes to Basquiat was bubbling away in his brain for a while, before it was finally made manifest in 1998, in response to being invited to exhibit at the Gramercy Park Hotel Art Fair, New York. In this series – which he returned to briefly before his death after a fascinating excursion into abstract painting – Bennett samples Jean-Michel Basquiat’s unmistakable oeuvre, taking on the American artist’s intuitive, bebop-imbued compositions and interlacing them with commentary on colonial invasion, Eurocentrism and the socio-cultural dispossession of Indigenous Australians.

Cited by Bennett expert Ian Mclean as his “most manic phase,” Notes to Basquiat analogises a meeting of the postmodern and the postcolonial; the former paradigm gaining sounder moral principles from the latter. The works on display here confer their critiques as collages of mostly pre-existing imagery, impossible to summarise yet at the same time clearly motivated by race and by discourse concerning the flawed universalisms of Western art history. But what does Bennett actually add to Basquiat’s obvious talent (a talent, we should remember, that was treated coldly by critics and art historians until a posthumous 1992 retrospective at the Whitney Museum, whose catalogue Bennett cites as inspiration)? What was Bennett hoping to bring to the already complex reputation of Basquiat’s work, which represents a black response to a predominantly white European art history and at the same time engenders “a black artist’s take on white artists’ takes on black art”?[5]

At least in this outing, Bennett is shown pulling the reins in on Basquiat’s legacy, bringing to his work a profound sense of history as unmoving; of the historically stuck. Basquiat, the eighties-bohemian art brand, personifies the romantic-creative desire to make oneself poetic – to transform, bend or transcend societal limitations. He was the free-jazz neoexpressionist, the intuitive scat-rapper scrawler unintimidated by Warhol, Picasso or Madonna, whether making his reputation in Rome or participating in the monied American hype machine.

Against the sheer charisma of Basquiat’s imagery, Bennett’s “notes” are resolutely reductive, and purposefully so. In the large-scale painting Notes to Basquiat: Psychopathic, Syncopation, Sycophantic, Symphony or Subject Matters (2000), a mix of expressionistic graffiti hieroglyphs, including a silhouette of Basquiat himself, flank a central list of words such as “coon stick,” “Abo Brand,” “white Australia” and “You’re Next.” In Bennett’s hands, no amount of creative genius can ameliorate, escape or subvert one’s historical context; no amount of artistic exuberance prevents one from being “subject to the continuous ‘play’ of history, culture and power.”[6]Basquiat, who had an uncanny knack for reinventing and re-threading historical continuums, ultimately gets stuck in Bennett’s consequentialist quicksand. The series suggests that the politics of being a contemporary Indigenous Australian is to experience the same old shit happening over and over and over again, election after election, “Closing the Gap” report after “Closing the Gap” report.

On account of its focus on Bennett’s preparatory methods, the QAGOMA retrospective shifts the perception of appropriation in his practice, from the act of copying to a protracted, sometimes years-long process. It begs the question of whether he really should be thought of more as a supplanter than a stealer, emphasising the paste over the cut. In I Am (1991–92) and The Coming of the Light (1987) – both on display here – Bennett takes celebrated New Zealand artist Colin McCahon’s “I AM” iconography and unseats it from its original charter. Christian uncertainty concerning the arrival of godly, spiritual light – which, for McCahon, is also doubt about everlasting relevance felt by most artists – becomes, for Bennett, Indigenous unease about this proselytising light’s dispersal of darkness, in all of its colonialist, primitive-correcting connotations. In the context of today’s identity politics, such a displacement may be inspirationally construed as a metaphor for the open-endedness, and ethics, of self-determination. I prefer to see it as yet another of Bennett’s erudite renderings of sociological limitation, alluding to how identity is always nebulously entangled with what society permits and suppresses.

A quick survey of the artists today who follow his lead will reveal how difficult all this is to actually pull off – to make art about social failings without perpetuating them, without requiring the problems for one’s critical brand. As Terry Smith noted in 1999, Bennett’s repeated use of binary symbols could easily lead him into a “psychic black hole,” towards an art of the “one theme rant” that would amount to “a kind of dancing better and better in the ballroom of the Titanic.”[7] The artist himself was wary of and fascinated by these risks. He toyed with both the dynamism and stasis of his black/white, abstract/figurative, inclusion/exclusion oppositions, asking whether anti-essentialism is even possible when socio-political change is a priority.

The title of Unfinished Business awkwardly echoes that of a prominent 2017–18 show at the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art: Unfinished Business: Perspectives on Art and Feminism. Hinting at a curatorial trend, it suggests there might be a remit for curators to instill their politically charged surveys with a more hard-won sense of incremental, daily practice—the quotidian, folkloric and “minor-key” aspects of political life valued, especially, by social media stooges. It’s true that, particularly in works such as Untitled (Nuance) (1992) and Psycho(d)rama (1990), Bennett mined his personal traumas and obsessed over identity categorisations. But, seen together, the works in this exhibition don’t suggest an overt association with day-to-day activism. Bennett is more old school in this regard, managing to be at once politically impassioned and soberly distant, framing first-person matters through third-person means. To this end, each stripe, splodge and splatter – whether aping Jackson Pollock, Piet Mondrian or Philip Guston – conveys the stilted grammar of information transferal, resonant with how the vicissitudes of his histories come off as causally determined, concocted or preordained. As he stated in a 1993 interview: “I’m not painting what I feel, I’m tracing it on the surface of the thing.”[8]

The “John Citizen” works – conceived by Bennett to be exhibited under this pseudonym—are, unfortunately, not well represented, possibly intentionally so, in order to distinguish it from the NGV survey. Still, there are enough to get the sense of how the strategy of speaking ventriloquially manifested throughout his career. It’s a by-proxy approach that can seem uncanny in some of Bennett’s more physical pieces, such as the Stripe series of abstract paintings he made between 2003 and 2008. These have generally been understood as signalling his break from politics; his “refusal to ‘communicate’” which entailed a retreat from postcolonial concepts to more painterly “ideas,” taking inspiration from the likes of Robert McPherson and Frank Stella. But I don’t buy it. To me the Stripe series is as critically and politically vocal as all the others, central to a career-long inquiry into the frameworks within which art obtains its meanings: through history, cultural theory, museum practice, private collecting, and, weirdly, via touch and surface itself. If purchased for private collections, they would operate much as the representations of abstract painting do in his Home Décor series, daring viewers to imbue them with his Aboriginality, probing what this might even mean. For Bennett, virtuosity was always so complicated.

Footnotes

- ^ Rex Butler, “The revolutionary: Colouring history,” The Australian, 31 August 2007.

- ^ Peter Schjeldahl, “Paintings by Aborigines,” The Hydrogen Jukebox, Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1991, pp. 303–06.

- ^ Gordon Bennett, Gordon Bennett: Selected Writings, Power Publications and Griffith University Art Museum, 2020, p. 121.

- ^ Zara Stanhope, Unfinished Business: The Art of Gordon Bennett, Brisbane: Queensland Art Gallery of Modern Art, 2020, p.15.

- ^ Jack Bankowsky, “Editor’s Letter,” Artforum, November, 1992.

- ^ Gordon Bennett, “The Manifest Toe,” The Art of Gordon Bennett, Sydney: Craftsman House/G+B Arts International, 1996, p. 33.

- ^ Terry Smith, “Australia’s Anxiety,” History and Memory in the Art of Gordon Bennett, Birmingham: Ikon Gallery, 1999, p. 17.

- ^ Gordon Bennett in Gordon Bennett: Selected Writings, Power Publications and Griffith University Art Museum, 2020, p. 132.