As a child growing up in Papua New Guinea in the 1950s I remember the expatriate community of white Australians driving into the Owen Stanley Ranges on weekends to barter newspapers for beautifully woven baskets made by local people. Sixty years later, the disparities in value (economic and cultural) that underpinned the colonial project in both Papua New Guinea and Australia – in relation to baskets, that is – has been challenged by a swathe of exhibitions across the country focused on revealing the beauty, utility and cultural significance of woven baskets from Pacific and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. Queensland has played a prominent role in this re-evaluation through events like the Cairns Indigenous Art Fair and almost three decades of Asia Pacific Triennials; the most recent including a focus on the fibre-based practices of women living in the Autonomous Region of Bougainville and the neighbouring Solomon Islands. Curated by Sana Balai and Ruth MacDougall, the “Womens Wealth” exhibition revealed the cultural value and cohesive power of women’s fibre practice in a society rebuilding itself after the devastation of the recent Bougainville crisis.

This is the curatorial context inherited by a new generation of professional Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island curators and scholars in Queensland. Freja Carmichael, a Ngugi woman belonging to the Quandamooka people of Moreton Bay exemplifies this new generation. In 2014 she completed a master’s degree in Curatorial Practice at the University of Queensland focusing on curating as a way of facilitating project processes that enable cultural maintenance and connection. In this she adds an Indigenous perspective to curatorial practices well established at the Queensland Art Gallery where curatorial teams develop exhibitions through extensive fieldwork visiting communities and nurturing relationships with artists. This practice is exemplified by the process that underpinned development of the “Womens Wealth” exhibition, as well as curator Diane Moon’s extensive engagement with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander artists and communities when developing the landmark exhibition Floating Life: Contemporary Aboriginal Fibre Art shown at the Queensland Art Gallery in 2009.

Carmichael was recently invited to curate Weaving the Way for the University of Queensland Art Museum as part of a broader curatorial project titled “Unlearning” that considers the ways that artists can deploy unlearning as a strategy to question received ideas or unconscious assumptions. The perceived bias against women’s fibre-based artworks that activated the re-evaluation of these traditions had in a sense already been addressed in the University of Queensland Art Museum through the development of a modest collection of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander fibreworks. Carmichael’s approach was not on reinstating the value of these traditions but on offering an Indigenous perspective on the field of practice. By basing her curatorial approach to Weaving the Way on three tenets of Ngugi culture: respect for ancestral ways, matrilineal exchange, and connection to land and water, she aimed to demonstrate the resilience of these traditions in communities from the Torres Strait and Cape York in the north, to Quandamooka country in the south.

Most of the seventeen artists[1] included in Weaving the Way live in the hinterland and along the Queensland coast. Almost all live in communities where their rights and responsibilities over country have been recognised through Native Title determinations enacted since the groundbreaking success of the Mabo determination in 1992.[2] It’s likely that the pride and confidence generated from gaining custodianship over country, along with ease of access to traditional lands and materials, have been factors in the resurgence of fibre-based art practice in areas severely disrupted by colonisation. Carmichael believes this was certainly the case for Quandamooka people when they gained land rights in 2011. For more than two decades her family has been actively engaged in social and cultural regeneration within their community; her mother and sister, Sonja Carmichael and Elisa Jane Carmichael are both artists whose weaving and painting practices are deeply engaged in interrogating cultural loss and reviving traditional processes.

Carmichael credits the cohesive nature of the weaving process itself as significantly contributing to this resurgence of fibre-based practice in Queensland. Used to signify connection, the term “weaving” has become almost a cliché in English. In the context of Aboriginal art practice, weaving retains this connotation along with its use as a catch-all loan word used to describe processes and products made using single element methods of looping, knotting, coiling, braiding and twining. Unlike the European version of weaving where practitioners usually work on a stationary loom, these hand-making techniques are characterised by their adaptability and portability as people travel across country in groups to collect, process and gather together plant materials to make fibreworks while sharing skills and stories.

The exhibition design echoes this movement as it creates a meandering path through the space alluding to the sinuous path of the Brisbane River as it winds its way past the University. As the title of the exhibition suggests, the process of weaving is presented as a kind of way-finding into the knowledge and cultural traditions of these communities. Selecting works from an established collection rather than being able to initiate a project-based process and engage directly with fewer artists at more depth, may account for Carmichael’s inclusion of just a few works by a relatively large group of artists, and their somewhat scattered staging in the small space. Her curatorial intent was most effective when artworks were grouped in ways that spoke to the cohesive nature of weaving practices while bringing out their cultural significance to the life of their communities, as evident in two paired baskets by Girramay man Abe Muriata.

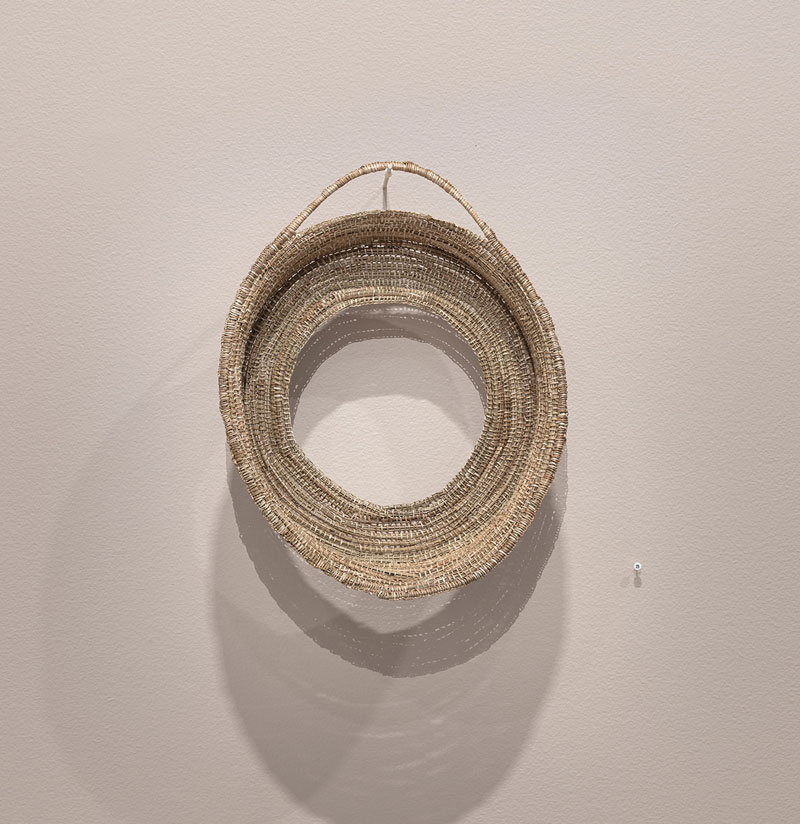

For more than a decade Muriata has been gathering lawyer cane from the rainforest on traditional lands north of Cardwell to make the distinctive and elegant Jawun, a bicornual basket used for fishing, gathering, and leaching poisons out of foodstuffs. Designed to be worn hanging from the head to free the hands for gathering items when traversing the rainforest, the form of the Jawun is perfectly suited for collecting foodstuffs, that while plentiful, are widely dispersed. In its sophisticated structure and economic use of natural resources the Jawun exemplifies the relationship of rainforest people to country. Muriata along with Jirrbal woman Desley Henry is one of a few contemporary artists making Jawun. He remembers his grandmother preparing the juvenile vines by removing their prickly spines and interlacing the tough and flexible canes to construct baskets when he was child. He taught himself the complex twining technique from observing Jawun in museum collections and from memory.

A Jawun remade in its traditional form hovering above the floor of the exhibition space honours this ancestral knowledge. Alongside sits a more crudely constructed version twined from chopped up garden hose. Devoid of function, this Jawun offers a telling commentary on the destructive impact of human intervention in to ecosystems nurtured for centuries under Aboriginal custodianship. The drought and wild weather that activated the recent wildfires in Queensland, have resulted in unprecedented destruction of rainforest, an environment identified by the sound of running water.

Opposite Muriata’s work at the entrance to the exhibition is a group of recently collected fibreworks by Elisa Jane Carmichael that reference the land and water of Minjerribah (North Stradbroke Island) and Moreton Bay, the traditional lands and waters of the Quandamooka people. A mission settlement on the island following colonisation, banned Ngugi cultural activities and severed the transmission of knowledge across generations. This resulted in loss of a distinctive netting process with Ungaire, a swamp reed native to the area, used to create flat bags characterised by parallel, diagonal seams of knots. Elisa and her mother Sonja Carmichael have been undertaking research into the construction of these bags in museum collections, and through experimentation are gradually reviving the process in order to pass on the knowledge as part of a process of “re-inheritance” for younger generations.

Elisa Carmichael’s fibreworks in Weaving the Way allude to this loss of cultural knowledge through holes that penetrate their structures. The open basket, Time has passed, and pieces are missing (2018) is coiled around an absent centre, while the gridded cylinder, We see your hands weave with us (2018) is constructed from techniques that encompass string-making, netting and coiling to create an airy compendium of traditional knowledge peppered with gaps. Her most recent work, Rain from the heart (2018–19) comprises thirty-two arm-sized rings made by coiling Ungarre and blue cotton threaded with mullet scales around wire and discarded sea rope found on Minjerribah beaches. While the work alludes to the salt water environment of Moreton Bay, it could also be thought of as a plea for rain as the title suggests. The implied movement of the arm bands scintillating with light caught by the tiny scales, recalls the way pearl shell is flashed in ceremony to mimic the lightning that foretells rain, by Aboriginal groups on the other side of the continent, on the Kimberley peninsula and in central Australia.[3]

The winding path through the exhibition space culminates in an ambitious artwork A Weave through Time (2017) by Torres Strait artist Grace Lillian Lee, borrowed from the Cairns Art Gallery. An Honours graduate in Fashion Design from RMIT, Lee creates body adornments using a palm leaf weaving “grasshopper” technique taught to her by Ken Thaiday; the linear structure of the palm leaf being perfectly suited to this form of concertina plaiting used extensively in the Torres Strait to make toys and baskets. Lee’s exuberant use of the technique to create sculptural forms for the body is connected to the spectacular diversity of body adornment traditions in Papua New Guinea.

Here, the process is used to visualise matrilineal connections between three generations of Torres Strait women. Each wears a cloak-like garment falling to her feet from elaborately wrought neckpieces, concertina plaited in materials that signify the different generations. The artwork includes the actual garments and a life-size projection of them animated on the women’s bodies, fading seamlessly from one generation to the next. The tensile properties of each material, plant fibre, cotton and plastic shift from the animated springiness of dried leaves, through cotton (in a garment tellingly called “white”) to the inert limpness of plastic. This sequence hints at the consequences of our increasing reliance on clothing made from unsustainable agricultural and manufacturing processes.

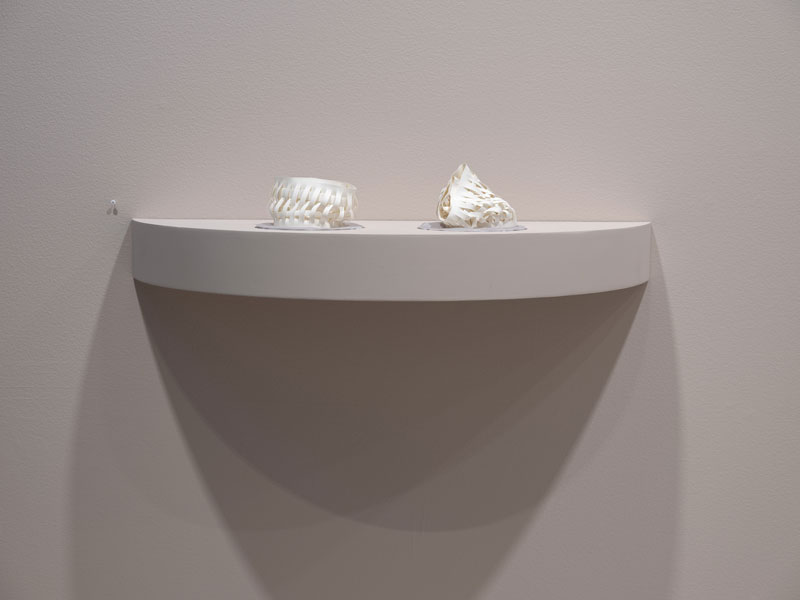

Lee’s work was advantaged by its scale and position at the end of the of the gallery while the presence of some smaller artworks was diminished by the high-ceilinged, stall like space with its perspectival focus overwhelming a more intimate, tactile apprehension of the work. The innovative delicacy of Janet Fieldhouse’s two small woven porcelain arm bands isolated on their plinth, could only be appreciated by awkwardly leaning into the space to look at them closely. A larger grouping of these works, or the inclusion of the traditional arm bands to which they refer, may have better revealed the two-edged meaning of the work; preserving the traditional form of the palm leaf armband worn by Torres Strait women by re-making it in the enduring but breakable medium of porcelain, is also to acknowledge that traditions, like fired clay, if not cared for are liable to break.

The performative nature of fibre-based artworks made in these communities and strongly implied in Elisa Carmichael and Grace Lillian Lee’s works was evident in another small exhibition of contemporary Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander artwork, curated by Carmichael at the same time as Weaving the Way. Called Seeing Country and shown at Redlands Art Gallery on Quandmooka country in Cleveland, an outer suburb of Brisbane, the exhibition was contextualized by a catalogue essay by Carmichael called “Ways of Seeing”. The title recalls John Berger’s influential television series and accompanying book, shown and published in 1972 to question the objectivity of vison, and assert that what and how we see is always inflected by what we know or believe.

Carmichaels eloquent essay offers a way of seeing the artworks in the exhibition through the prism of her reclaimed knowledge of the relationship between seasonal cycles on Quandamooka land and sea and the patterns of traditional life. In spite of the title, the artworks in Seeing Country go some way to up-end the primacy of vision in knowledge formation by bringing attention to senses other than sight; the tactility of ceramic and woven forms, the smell of plant material and possum skin, and the sounds and kinesthetic experience of moving through country shown in an accompanying video that introduces viewers to the multilayered knowledge of clan groups gathering reeds for weaving or foodstuffs for eating. The value of Weaving the Way and Seeing Country lies in their provision of access to Aboriginal ways of knowing country and creating community through artworks that trace contemporary ways of performing knowledge, through gathering and making practices held on country as acts of identification and responsibility.

Footnotes

- ^ The artists in Weaving the Way include Daniel Beeron Galaman, Elisa Jane Carmichael, Janet Fieldhouse, Davina Harries, Doris Kinjun, Grace Lillian Lee, Abe Muriata, Emily Murray, Debra Murray, Susie Pascoe, Cecilia Peter, Dorothy Short, Eileen Tep, Delissa Walker, Maria Ware, Rita Wikmunea, Hersey Yunkaporta.

- ^ Native Title Information Handbook: Queensland, Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies [AIATSIS], Canberra. 2016, pp. 11–19.

- ^ Kim Akerman with John Stanton, “Riji and Jakoli: Kimberley Pearl Shell in Aboriginal Australia”, Northern Territory Museum of Arts and Sciences, Monograph Series 4, Darwin. 1994, p. 19. Akerman notes that Kimberley pearl shell traded along routes to Central Australia is regarded as water. “Water rain, lightning: factors in the seasonal re-awakening of the land after long dry periods are all embodied in the shell”.