![GOMA_APT9_installationview_20181123_nharth_016.jpg] Gunantuna (Tolai People), Gideon Kakabin (lead artist), Loloi (shell money ring) and Tutana (largest shell money rings) with Ulang and Rumu (ceremonial spears), installation view, 2017. Image courtesy the artists and Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art. Photo: Natasha Harth, QAGOMA](/uploads/articles/APT9_1.jpg)

When the Asia Pacific Triennale began in 1993 it occupied a unique position as the world’s first recurrent exhibition devoted to the art of the Asia Pacific. Its 25-year history has seen the rise of early participants Ai Wei Wei and Yayoi Kusama, and with them the evolution of the relationship of Australian audiences to contemporary art. The APT has played a leadership role in showing art from Asia, the Pacific and Australia alongside each other, and building enduring professional ties across the region as well as contributing to a more inclusive, global art history.

A pronounced emphasis in APT9 is the work of Indigenous and Pacific peoples and their commitment to honour their cultural heritage in ways that are meaningful and relevant against the mounting tide of uncertain futures, declining natural resources and the impact of climate change. Led by practitioners, with an opening weekend of performance, ceremony and weaving workshops, the agency of women and of inter-cultural and inter-generational exchange was a high point.

Building on the memorable “actiVAtions” of Rosanna Raymond and the SaVAge K’lub (2010–ongoing) for APT8,[1] which occupied GOMA and forced the issue of live nudity in the museum, this APT also gave prominence to key Pacific works, including Lisa Reihana’s celebrated In Pursuit of Venus [infected] (2015–17) and Taloi Havini’s further-expanded Habitat (2017–18)[2]

The Women’s Wealth project, involving Sydney and Bougainville-based Havini, Australian artist Kay Lawrence, working with co-curators Ruth McDougall (QAGOMA) and Sana Balai from Buku Island, focused on the collective work of learning traditional craft skills, gathering, dying, and weaving natural fibres supported by video documentation that recorded the community consultation, was one of a number of key displays across QAGOMA that looked at the centrality of women’s fibre work. Another was the inclusion of the customary mats by the Jaki-Ed weavers from the Marshall Islands, accompanied by a spoken-word performance by poet Kathy Jetnil-Kijñer, invoking this Oregon-based artist’s role in addressing the 2014 UN Climate Summit and broader discussion of women’s roles against the backdrop of the fraught nuclear legacy of weapons testing in the Pacific.

As these latter works demonstrate, such “customary” or relationally framed aesthetic practices, privilege both origins in land and society and ongoing personal agency. As evolving craft traditions in a range of diverse media there is much to be appreciated in the richness of texture, forms, pattern and imagery of these works as alternative aesthetic trajectories to the dominant forms of Western art history. In an example of this, ceremonially greeting visitors as they passed through the entrance to the Gallery of Modern Art (the traditional spot for a donor’s acknowledgement board) an installation work by the Gunantuna (Tolai People) made explicit the economic base of customary practices, as it became apparent that the spears with their wreaths of shell beads were the embodiment of shell money – the traditional signifier of wealth and status.

At the media launch and symposium, QAGOMA Director Chris Saines made a point of reiterating the concept of “conceptual equivalence” between customary cultural practices and contemporary art as a key curatorial agenda. This expansion on the inclusion of traditional Indigenous cultural practices in Australian-based survey exhibitions has been a regular fixture since Bernice Murphy’s 1981 Perspecta and the inclusion of the Aboriginal Memorial (1987) in the 1988 Biennale of Sydney as a further key international milestone. But the APT still serves to highlight the challenges in presenting an exhibition such as this, incorporating object-based and material work alongside graphic, pictorial and projected media, underlining at times significant inequalities between discourses and differently developing economies of thought and practice.

Championing these concerns, the crowd-sourced installation of tools, feathers and sound (voices) by Jonathan Jones, conceived with Wiradjuri elder Dr Uncle Stan Grant Senior, is an elegant convergence of culture and language presented as a magnificent arc of movement that appears to represent the winds of change. Also distinctive, the earliest works in APT9, a series of drawings by Buka artists, Herman Somuk from the 1930s and 1940s and Gregory Dausi Moah from the 1970s, depict daily custom and major conflict. These drawings were reminiscent of the compelling graphic works of Australian Indigenous artists William Barak and Robert Campbell Jnr.

And, if drawing was the portable medium of the nineteenth and early-twentieth century, then digital’s transferability has led to its ubiquity today, as experienced in Taloi Havini’s lush, panoramic video of a post-colonial, post-industrial landscape scarred by civil war. The work of the NT-based Karrabing Film Collective, a conversation around communities negotiating trauma, also reflects a shared motivation to deal with the issues at hand.

For an artist, such as UK-based, Karachi-born Rasheed Araeen, renown for being fearless and outspoken in opening up discourses of art through the journal Third Text, but also through his work, there is a clear concern to locate alternative forms of practice in ways that command a global space. Araeen is represented by two distinct strands of work – through one of his colourful modular minimalist assemblages, and through photo montage works, Forever Green (1988) and La Grande Jatte (1991–94), that play on Western colour theory and familiar picturesque landscapes, asserting counter histories of green as the colour of Islam and the Pakistani flag, and a redacted military aerial image as a retake of Seurat’s pointillism.

A further highlight in this reframing of modern art histories (also recently invoked in the Australian context through The Field Revisited at the NGV) was a recently rediscovered work by Filipino artist Roberto Chabet. This impressive room-size installation, Waves (1975), not only captures its dominant motif as a classic form of serial repetition and movement, but uncannily projects current concerns around the rising sea levels of the Pacific.

Overall, APT9 is a careful and modulated exhibition, with satisfactions to be found in its particularities rather than in grand gestures or sweeping claims. In dealing with divergent practices – individual, collective, customary, modern and contemporary – it takes care not to over-emphasise similarities and symmetries nor competing worlds. This judicious approach is most appealing in the correlation of subtle atmospherics and allegiances.

Connections abound, as in the surface shimmer and lustre of the ocean’s poetic and mercantile connotations in Monira Al Qadiri’s video installation, DIVER (2018), as it connects with Tada Hengsapkul’s filming of decommissioned army tanks submerged off the Thai coast in You lead me down, to the ocean (2018), which brings to mind Jun Nguyen-Hatsushiba’s iconic film of underwater cyclo drivers for the Memorial Project Nha Trang, Vietnam: Towards the Complex for the Courageous, the Curious, and the Cowards (2001). Or, again, formal correspondences resonate across Ayesha Sultana’s graphite abstractions, Jananne Al-Ani’s aerial-filmed archaeology of ancient fortificationa and defunct oil storage facilities and Ly Hoàng Ly’s cast cow bones.

Chen Zhe’s photographic archive devoted to her sensitivities to the phenomenon of twilight shares a liminal sensibility with Munem Wasif’s elegiac video of a long afternoon in Old Dhaka. Kheyal (2015–18) conjures a magical realm in which real and fictitious characters materialise and disappear. Although strangely adrift, they evince a self-possession that seems only possible in the shadows of the old city, particularly in the light of Bangladeshi photographer Shahidul Alam’s arrest last year.

Composed around influences such as dystopian fiction and Chinese opera, Cao Fei’s video Asia One (2018) also envisages an increasingly believable scenario in which the largest automated distribution centre in China orchestrates a romance between its two remaining human employees. Continuing this theme of the inevitability of artificial intelligence, Jeong Geumhyung’s inventory of sex toys, medical devices and home hardware may offer everything that one could possibly need for wellness and gratification but its ambience is disturbing, the very opposite of wholeness.

Returning to Australia, the performance work of Australian-based Tongan artist Latai Taumoepeau is a provocative embodiment of actions that attempt to decolonise the self, exemplified by a key work of performance as photographic documentation in which she mimics Western notions of beauty by spray-tanning her dark skin. The resulting image reveals a regal figure whose glistening body accentuates a female Pacific body politic. In a complementary work of wry humour, Western Arrente painter Vincent Namatjira installs his legendary “rogues gallery” according equal value to seven APY Lands law-men, seven Australian prime ministers and seven of Australia’s richest people.

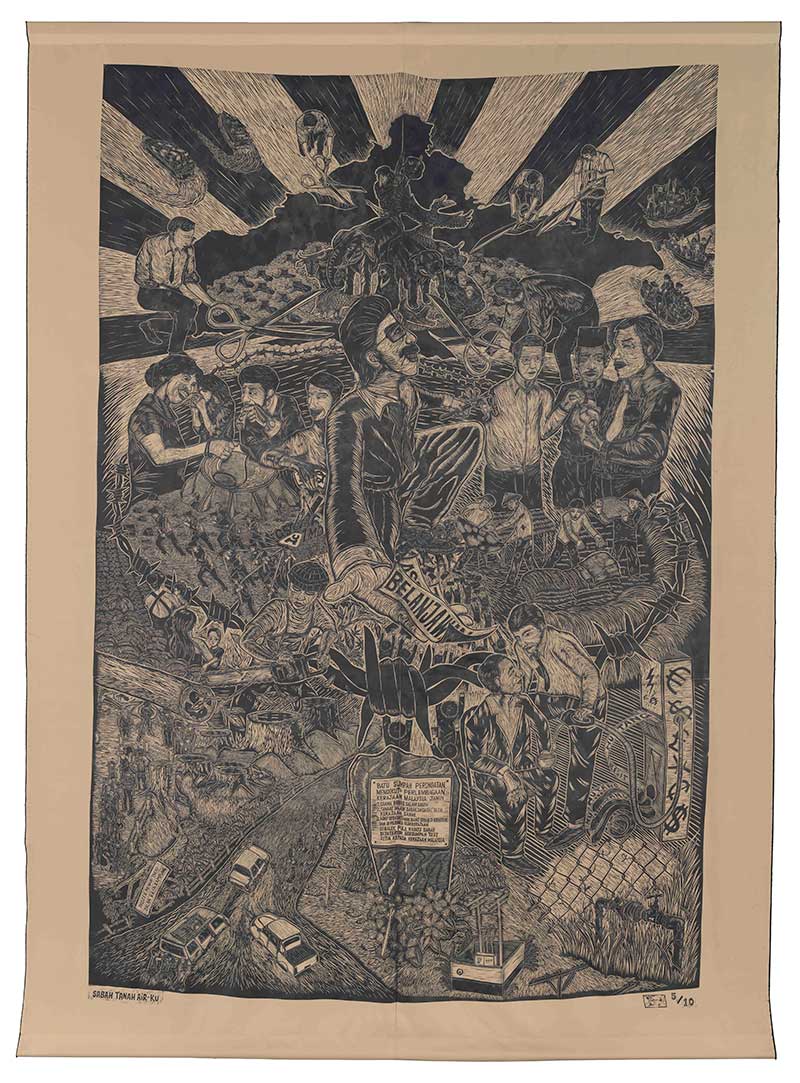

Similarly challenging the status quo, Pangrok Sulap, the Sabah-based collective of indigenous artists and activists, has sought to communicate the aspirations of Borneo’s regional communities – adding woodblock printing to its repertoire after learning the technique from fellow punk bands in Jakarta. Recently censored in Kuala Lumpur despite working under the imprimatur of a Japan Foundation-funded exhibition, the inclusion of its festival-scale woodcut in the APT has led to the reinstating of its imagery in the Malaysian public sphere. To the satisfaction of the local art scene, it recently appeared in the English language Star newspaper, which reported on the APT.

While these works place the human hand and individual and collective purpose at the heart of APT9, a more conceptual disembodied aesthetic is also at work. It threads through the exhibition in Mithu Sen’s linguistic interruptions, in Shilpa Gupta’s flapboard signage and in the scrolling exhortations mounted on a crucifix by duo Young-Hae Chang Heavy Industries. These typographical interventions are linked to Sawangwongse Yawnghwe’s genealogies of Myanmar state power, a schema of the connectivity between the individual, the bureaucracy and the corporation. Yawnghwe’s life-long exile since his birth into the Shan resistance movement can only be fully understood in terms of its intersection with market forces.

These more detached and distributed text-based works lend an important element to the show, providing a necessary counterpoint to the immediately locatable works which centre on place and material. Other works in the exhibition which arise out of the digital-mediated slippages of contemporary life remind us that the particularities of place and material constitute forms of agency and resistance that are no longer possible or desirable for everyone. In the face of a world increasingly shaped by financial speculation and digitisation, greater emphasis on a wider range of strategies being used by artists would have sharpened our reception of all the works in APT9.

Footnotes

- ^ See two key Artlink articles covering this event: Dan Taulapapa McMullin, “The Acti.VA.tions of Rosanna Raymond”, Artlink 37:2, June 2017: https://www.artlink.com.au/articles/4603/the-activations-of-rosanna-raymond/; Léuli Eshraghi, “On First Nations agency in our European-based institutions,” Artlink 36:1, pp. 42-49: https://www.artlink.com.au/articles/4437/on-first-nations-agency-in-our-european-based-cult/.

- ^ See two articles by Nicholas Thomas, "Lisa Reihana: Encountes in Oceania", Artlink 36:2, pp. 22-27: https://www.artlink.com.au/articles/4595/lisa-reihana-encounters-in-oceania/;"Human flow in Melanesia: Taloi Havini's Artefacts and Habitiats", Artlink 38:3, pp. 38-43: https://www.artlink.com.au/articles/4702/human-flow-in-melanesia-taloi-havinis-artefacts-an/