The promise of virtual reality (VR) has been with us for several decades now, with the term coined by Jaron Lanier in the 1980s. An evangelist for this emerging technology, Lanier’s company VPL Research, developed and distributed early and costly virtual reality headsets. But it never really caught on. That’s until 2014 when 22-year-old Palmer Luckey, a fan of The Matrix films and Neal Stephenson’s virtual-reality novel Snow Crash, sold his company, Oculus VR, to Facebook for $US2.3 billion.[1]

Like the internet itself the progenitor of VR is the military, as noted by “the philosopher of cyberspace” Michael Heim, “A prime example of immersion comes from the U.S. Air Force, which first developed some of this hardware for flight simulation. The computer generates much of the same sensory input that a jet pilot would experience in an actual cockpit.”[2] From its development as a tool for military training, to its commercialisation in Silicon Valley, this technology is now mainstream and affordable to the creative industries, among them a new generation of artists, writers, filmmakers, and other cultural producers engaged in creative world-building.

A starting point for this issue of Artlink is John Berger’s influential television series and subsequent book Ways of Seeing (1972). Berger and his collaborators speak of how imagery is constructed and how the gaze is manipulated and influenced by the makers of those images. The act of creating and viewing an image is never passive, the maker and the viewer bring their culture, their histories, their perspectives to the act of seeing. “We never look at just one thing; we are always looking at the relation between things and ourselves. Our vision is continually active, continually moving, continually holding things in a circle around itself, constituting what is present to us as we are.”[3]

.jpg)

So how do technologies such as virtual reality influence the way we see and what does it offer for contemporary image-making? The writers for this issue have been invited to contemplate this changing landscape, to explore how artists and museums are engaging with VR and where the audience becomes part of the artist’s vision as a “player” and agent. As with the application of all new technologies, artists are driven to probe, experiment with and sometimes break the machine, challenging the possibilities of the medium.

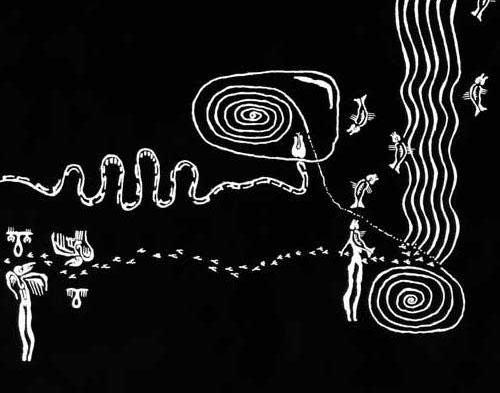

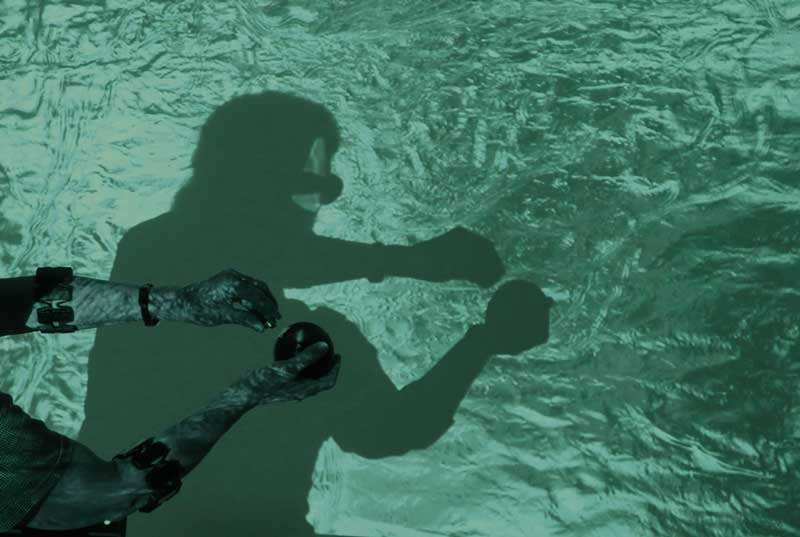

Notably, in the intersection of arts and virtual reality, women have been pioneers in the field. Brenda Laurel started her career in gaming and interactivity at Atari in the 1970s and at the same time received an MFA in Acting and Directing. Going on to work at Apple and as an educator, she has published several books on human-computer interaction, design and theatre. In her essay Claire L. Evans writes on Brenda Laurel’s 1993 VR work Placeholder, produced by Interval Research Corporation and The Banff Centre for The Performing Arts. In this significant early VR artwork, Laurel sought to explore how players or “immersants” interact and negotiate with each other in a VR environment, merging her interests in theatre, coding and nature.

Jill Scott’s more recent Eskin4, discussed in this issue, similarly functions as electronic interface with a capacity for bio-mimicry discussed in connection to this artist’s expanded approach to practice working with augmented reality, which overlays computer generated imagery onto “real world” situations. Working with vision-impaired young people and environmental groups, Scott’s practice is here framed by Rob La Frenais as an example of “the distributed virtual,” discussed alongside other recent works by Minna Långström and Kathleen Rogers that also function as bold forms of experimental and interactive research into new fields.

.jpg)

A ground-breaking Australian artist, Scott’s own career has taken her from the early days of virtual reality to a time when the technology seems to be making a comeback. Building on the early work of Laurel and other pioneers, many of the artists profiled here continue to explore the potential of VR to immerse the viewer and challenge the limits of the body. These include the practice of Eugenie Lee, whose Seeing is Believing, is the outcome of a residency at Body in Mind (BiM) at the University of South Australia, a research group developing better treatments and preventative strategies for people who suffer from chronic pain.

While the focus for artists is on creating immersive experiences, it is a challenge for museums, galleries and film festivals to present VR work. There are clear limitations in the design of appropriate exhibition and 1:1 user interfaces. Often the audience experience is of queuing up in line to be seated in an office swivel chair in a gallery or film festival foyer and having an attendant fit the head-mounted device for you.

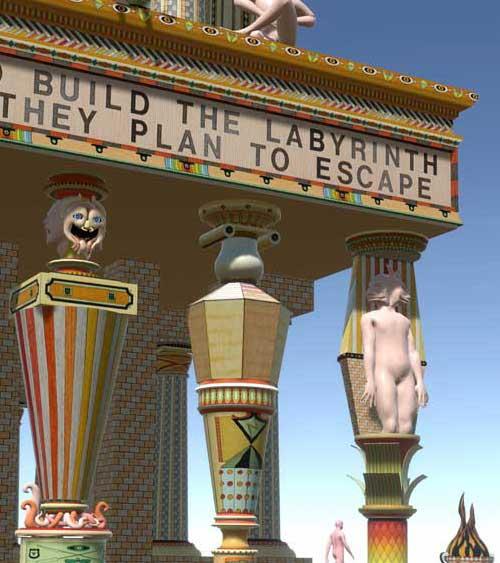

An exception to this model, more fully embracing the multi-dimensional space of the exhibition encounter, is Terminus (2018), one of the Balnaves Contemporary Art Interventions on view earlier this year at the National Gallery of Australia. Installed as stations in a maze-like garden of interior spaces that matches that of the virtual world, this new work by Jess Johnson and Simon Ward is like a fantasy playground where one is invited to “choose your own adventure.” But there is more to this décor world than just eye candy, as Denise Thwaites corroborates in her essay “Ways of (Not) Seeing,” re-visiting Berger’s text to ask how VR can embrace contemporary perspectives, where the potential of artificial world-building engenders immersion, distraction and escapism.

.jpg)

In the detail of the chosen cover image, this is but one instance of the multi-layered fantastical world of symbols, humanoid figures and Escher-like mazes and walkways that feature in the animations of Johnson and Ward. Here the eye looks back at us but is also the barred entrance or gateway into a tunnel or portal to another level. It is a perfect representation and metaphor for VR, an ocular space in which sight and vision are privileged, and where the eye leads and navigates us deeper into the maze of working worlds.

Another recent work which embraces VR’s physical and virtual capacity as an empathy machine, dealing more directly with the challenges of lived experience is Carne y Arena by filmmaker Alejandro Iñárritu. Premiering as the first VR Official Selection at the 2017 Cannes Film Festival, the work conveys the plight of a group of migrants crossing the US-Mexico border. Here the participant is embedded in this harrowing experience through the virtual encounter augmented by the direct physical sensation of feeling the sand beneath one’s feet, and the confinement in a cell-like space. As such a powerful and immersive but also critically engaged film work demonstrates, there is great potential to incorporate a range of modalities and senses to enhance and physically locate the viewing experience.

.jpg)

VR has great appeal to cultural institutions looking to enhance the audience experience, as demonstrated in a recent work commissioned by the Toi Art gallery in the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, Meet Lisa Walker in her Workshop, as an accompaniment to her recent solo exhibition. Likewise, I await with much anticipation the pending launch of two new ACMI | Mordant Family VR Commissions of new work by Joan Ross and Bidjara artist Christian Thompson.

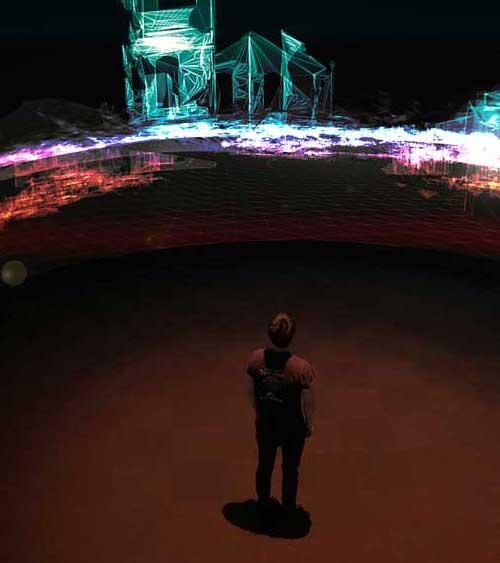

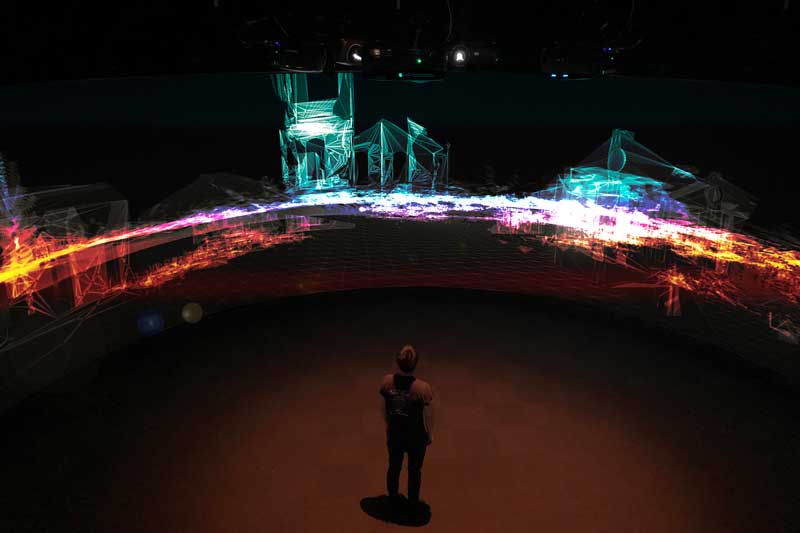

Andrew Yip, research fellow and resident 3D artist at the iCinema Centre for Interactive Cinema Research at the University of NSW has contributed an ambitious overview essay of working methodologies that also expand on the role and agency of artists in museums. His research, drawing on the metaphor of the time‑traveller in the 1895 novel by H. G. Wells, draws out new ways to revivify archives as both a means of looking back and contemplating our futures, well‑demonstrated through Yip’s own VR work that transports us back to the fields of Villers Bretonneux in 1918. His essay “Metascapes, memory and spacetime: VR in the museum and archive” responds to this new space for creative production and archive consumption, sitting somewhere between the much‑vaunted allure of VR as a vehicle for empathy through proximity and the means to anticipate new futures.

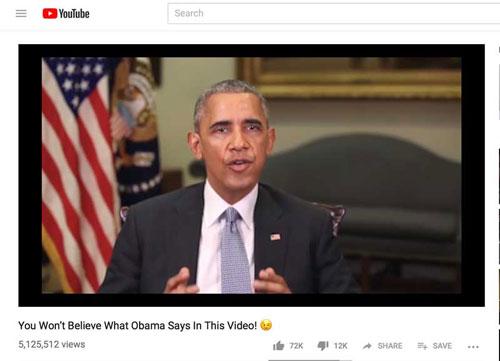

There is of course much that is balefully wrong about the application of VR and associated technologies, as wrestled with across this issue by artists working as disruptors to call out, as Ian Haig puts it, the often “badly rendered potential of VR.” Similarly, Sean Dockray’s interest in the exponential rise of the “deepfake” exploits the role of machines and artificial intelligence (AI) in generating imagery that appears to be real but is entirely manufactured through algorithms, neural networks and machine learning.

In his opening feature, Kit Messham-Muir takes a productive but critical view of VR’s misty-eyed claims, resembling something of a two-headed hydra, with its great promise as a natural progression for many video artists to embrace the 360-degree audio-visual surround, resulting in phantom-like outputs. Using the aptly titled and energetic example of the Australian BADFAITH collective, itself a take on cultural failure inspired by Jean Paul Sartre, Messham-Muir profiles a series of new works that take on the metaphor of the “exquisite corpse,” experienced in bits and pieces.

It is still early days for integrating VR technologies into exhibitions and no doubt the audience experience will improve as the technology becomes increasingly adaptable. But, at this time, when virtuality is in fact a reality and we live in a visual world dominated by real, manufactured and fake images, what can art offer? I go back to Berger for an answer, when he says, “The art of the past no longer exists as it once did. Its authority is lost. In its places there is a language of images. What matters now is who uses that language, and for what purpose.”[4]

Footnotes