… in the deserts of Australia lived an extremely rare nocturnal bird … it disappeared at the end of the 19th century …

Night Parrot Stories (2016, Dir. Robert Nugent)

In the year of Archie’s birth (1970) the novel A Horse of Air won the Miles Franklin Award for literature for a particular view of Australian life.” The title and narrative refers to the “carousel-like” galloping horse, and low-flying flight actions of the Australian Night Parrot as described by Aboriginal people. The rarely sighted bird has until today been invisible and thought extinct. Unseen in the night it can only be seen through its trace, droppings and footprints left behind. It exists as a presence, the sounds of its wings and movement through the air or smells.

This is the review of another rare native bird. Archie Moore’s career has been created around ideas, inviting the audience to interact through all our senses, and to be directly experiential rather than solely focused on a “visual art” object. Moore can paint but plays on smell, taste, touch and sound as much as sight, and even here interrogates text to support numerous meanings. In this commissioned retrospective installation, Archie takes the audience into a set of rooms, spaces of memory and names as mnemonic devices from his own life to provoke an automatic response and release coded and stored emotions. These works represent songs of innocence and songs of experience (Blake), memories and pains and doubts of childhood.

Give me the child for the first seven years and I will give you the man.

The exhibition, consisting of an outside house plan, a wall drawing and seven rooms is a book of threes, within three parts: outside, intermediate and inside, and also past, present and future—representing the development of Archie Moore’s existential nature and amazing imagination. Firstly, the 1:1 floor plan of Archie Moore’s childhood family house in the western Queensland town of Tara, reconstructed with the assistance of Indigenous architect Kevin O’Brien on the lawn of the courtyard outside the gallery. Drawn in white lines with a tennis court marker, it’s a Dogville-like, Brechtian theatrical device, belying a story of a similar life of “dirt” poor fringe families, described by Archie as “you could always tell if someone was home just by looking though the sizable holes in the walls.”

Such a spare rendering of houses is often used by children in games, but in serious theatre it is a tool to focus the attention away from the set to the action of the players and the story being told. The drawn house without walls also points to the visibility of the inhabitant’s lives to the town’s other citizen; to their problems with poverty, dress, health, nutrition, supposedly crude social interaction, and negative view of the future, in this case, a legacy of the colonisation of Australia. A life, a colonial history, being played out in plain sight, but ignored, like turning a blind eye.

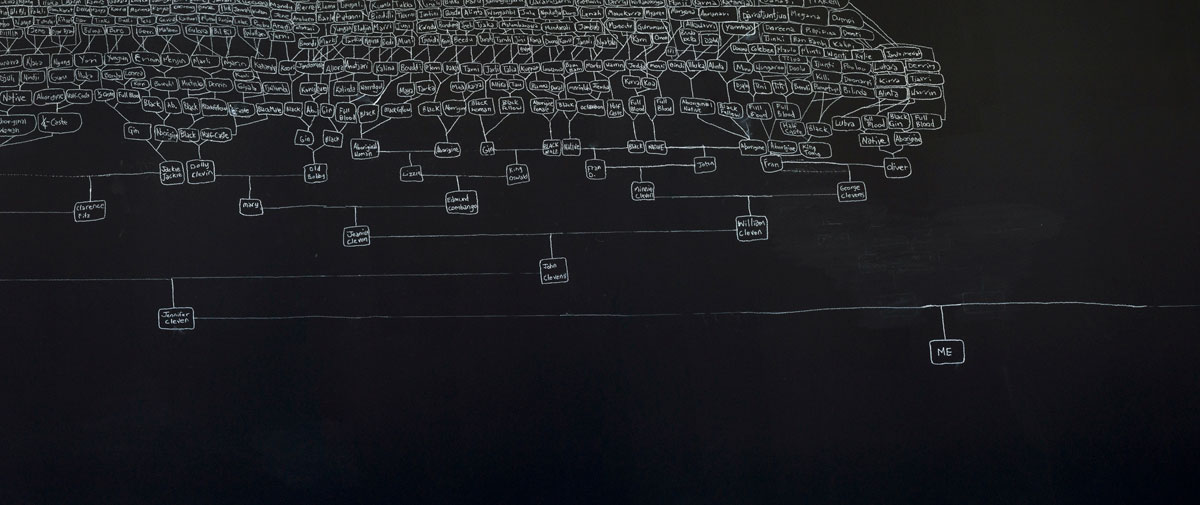

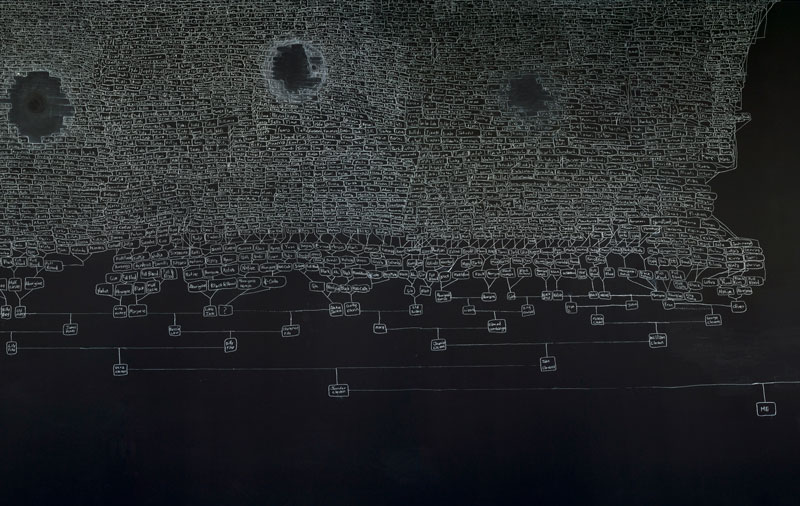

A family life can be a work of art. A large twelve-metre long, five-metre-high blackboard and chalk Aboriginal family tree drawing welcomes you into the building. The descent-line record reaches back thousands of years from known named people like the artist himself; a box on a long limb at the bottom enclosing “Me,” back into the past, to “A Full-blood Aboriginal” and those existing only as numbered individuals. Normally these diagrams drawn up by anthropologists, revolve around an “ego” depicted by a triangle for males (to the left) joined to circles for females (to the right).

Social workers now depict an apparently non-gendered ego as a square called “genograms,” and interestingly in using the “social worker” boxes system Archie’s family tree could appear to be (intentionally or not) described in postcolonial terms through the dominant social worker interaction in Aboriginal life as “traditional” anthropologist fieldwork. I imagined Archie drawing in a scene featuring someone like Einstein constructing an algebraic equation to solve an intangible, immeasurable, problem.

Traditionally, God can appear in Aboriginal life as a flash of white light or a refraction of light into the rainbow spectrum colours. Certain creatures display this refraction: the skin of reptiles, wings of certain insects, shellfish, and the scales of fish. Archie Moore meticulously drew row upon row of flat rectangular boxes in his family tree, that run down the wall like scallop-oyster beds, fish scales, or like a dripping broken honeycomb. Both metaphors (my own) are very evocative of life, sex, regeneration, vitality, and potency. And they are very totemic and Aboriginal.

.jpg)

There are three, black, reasonably large holes in this constellation of ancestral star heroes around three quarters of the way up the wall in this web—one I’m told was a major massacre event that leaves a gap in the record, another black empty space to the right around the same time records a devastating smallpox outbreak, and the third represents a destroying of records from negligence, fire and other natural disasters, or a deliberate act to cover crimes of embezzlement, murder or mismanagement.

Does the use of rooms mean a form of domestication–assimilation as a colleague has suggested? Possibly, but it could also be Moore’s intent; that of actively classifying and not just being classified—put it in a box—and naming; his own taxonomy as family tree positioning. There is the use in the “living room” space of a dead cockroach specimen (American); “I always thought they were oriental” (Archie Moore), “I thought they were German” (Djon Mundine). Even the most unpleasant, creepy crawlies are classified in detail.

I once attempted to place a curtain in an exhibition to prevent sound and light bleed but was told that audiences would simply not go through the obstacle. But Moore didn’t care if there was sound or light bleed, it glued the experience together. Moving up to the gallery space proper the viewer is confronted by a wall across the room with three well- used recycled doors marked with stains of people’s hands, telling other people’s stories, from other people’s lives. The physical, the spiritual–emotional and the intellectual; right, left and the third path, good. This is Blake’s “Marriage between Heaven and Hell.”

Or, with so many Aboriginal artists completing an academic Doctoral degree, it is more like thesis, antithesis, and conclusion. You’re required to choose, which to go through, as with the academic entanglement—many I’m told were seriously confronted and confused, reluctant to make a choice.

If the doors of perception were cleansed everything would appear to man as it is, Infinite. For man has closed himself up, till he sees all things thro' narrow chinks of his cavern.

The Doors of Perception, Aldous Huxley, 1954, quoting William Blake

About the time that William Blake wrote the above concerning the middle path, it was the time the British began to colonise the Australian continent. The land, its Aboriginal people and other inhabitants were so unfamiliar and counter to those of the European experience, they were thought of as the world upside-down; more than their physical forms, it was their minds and way of thinking that were all-the-more challenging and misunderstood. For Aboriginal people, it certainly became an up-side-down world following the colonial arrival.

The middle door facing the viewer in this exhibition, most often chosen, leads to a small dark, dead-end but contemplative room, with a moving image of the outside reception area on its back wall – a Camera Obscura (Darkroom) (the word camera meaning box-room). As Moore explained, “I first saw a projection one day as a natural occurrence, through a hole in our front door, and I was amazed at this natural but somewhat ghostly occurrence, a wonderment, seeing a natural projection. It took a bit of time to figure out what the upside-down image was.” More than a plaything, it points to the fact, that as much as his poverty-stricken family were the subject of observation, ridicule and amusement of the outside town population, at the same time Moore was silently observing them from a physical, moral, reverse view, casually but carefully watching and thinking on their unconscious social, often perverse, actions.

The central door and image possibly breaks down any fear and anxiety of what lies ahead and encourages you to have fun and venture into the maze. The third door, to the right, opens into a hallway as one might enter a normal suburban house. A faint whiff of the familiar odour of Dettol antiseptic hanging in the air refers to both the insistent “cleanliness next to godliness” of formal good Christian “white” Australian society and his mother’s striving to attain this, in reality—white society’s double standard as the status of normality. We used Dettol freely in my own family, and I remember my mother once used sheep-dip to rid our house of a flea plague.

A holy picture starts a line of standard hang as a framed artwork along the wall on the left. Proselytising Christian sects often prey on the anxieties of the poor, and this first image is the first image that Archie was given by such a group—a paint by numbers picture for children when he was a small child. The other images are some of his early works created at the Queensland University of Technology. The hall leads to a living room; Camera Familiaris (Living Room), seemingly a children’s play room with an old-fashioned black and white TV playing a type of trickster spirit, Huckleberry Hound (from 1957) and the Banana Splits (from 1968)—this is pre-The Wiggles(1991) or Bananas in Pyjamas (1992).

Scribblings in biro are found across the sofa and on the walls: “though we seemed to be poor and deprived, other kids were really jealous of us, because we were allowed to draw on the walls and furniture, and ride our bikes through the house.”(Moore). A kerosene refrigerator reminds Archie of another inside-outside experience when, as a small child, he became accidently locked in an old refrigerator but luckily rescued. This happened often fatally in those times, and doors were removed from all abandoned refrigerators for this reason.

I knew I was black of course, but I also knew I was smart. I didn’t know how I would use my mind, or even if I could, but that was the only thing I had to use and I was going to get whatever I wanted that way

James Baldwin, in James Baldwin, 1924–1987 ( Dir. Karen Thorsen)

There is schooling and there is education. The next room; Camera Schola(Schoolroom), is ambiguously reached though a sliding door recycled as a swinging door. A duplicity continues through the room and experience in a projection of government films of the time, pushing the benefits of the mining industry of the time in “opening-up and developing” the nation. A pair of small desks-chair sets that seem, to me, incredibly small contain common objects, books and pens.

And some time in an instinctive way, I knew that what was happening in those books was also happening all around me, and I was trying to make a connection between the books, and the life I saw, and the life I lived.

James Baldwin, in James Baldwin, 1924–1987 ( Dir. Karen Thorsen)

Voices, a book of mainly male poems written after WWI caught the eye of visiting curator David Elliott—this was also part of his school experience. Despite the jibes and comments, it was here that Archie discovered books and reading. Much has been made of to the mental depression, the dearth of a positive view of the future following the First World War—a Durkheim loss of the spirit (anomie) and sense of social stagnation and boredom (ennui). For Aboriginal people, a similar struggle for the spirit takes place daily.

If one enters Archie’s labyrinth through the first left door, you come into the Camera Verbum (Word Room); another child-like space of quiet observation. Like a child in bed listening to sounds and conversations in the dark. In the space, words in large white letters are projected on the black walls—words, insults and more heard from outside people passing by on the left, and those remarks heard spoken by his family inside the house, dad jokes and witticisms, nick-names and banter. Interestingly, the more complex and sophisticated words are produced within, rather than the common insults of the town people.

Jill Bennett’s publication Empathic Vision: Affect, Trauma and Contemporary Art (2015) examines the cultural impact of generational trauma and loss, especially social disruption resulting from the colonial experience. This is the focus of the next room; Camera Affecta (Mood Room) is an empty, unlit room with drisping wisps of fog, and loud groaning sounds, possibly mechanical. In the award-winning Australian horror film The Babadook (Dir. Jennifer Kent, 2014) an evil spirit haunts a young widow and her son to the edge of insanity. It’s fought and resisted intensely until finally they’re able to capture it and lock it in the cellar. A reading of the story is that the entity is thought to be the embodiment of the residual grief at the husband’s death (the boy’s father) in a car accident on the way to the maternity hospital. In the end they learn to control, accomodate and live with it.

If we turn right away from the dark we move into the light of Camera Lucida (Light Room). A row of fake antique plastic pots, are lined up on a bed of cracked clay. The potted palms are those seen in every office and middle-class home; grown such that they appear to be plastic and the whole installation to be artificial. Nearly all artists struggle financially and my first impressions of Archie Moore was of a couch-surfing transient individual. He would appear at my BBQs as though he’d just come from a nearby party place the night before, and would just as often stay over which I enjoyed. Every artist struggles with integrity strain as they become successful; how do they retain their political edge—what Tom Wolfe called the “boho dance.” This is doubled in the case of Aboriginal artists, given the nature of the commercial market.

Many, if not most, Aboriginal children spend a considerable amount of time with their grandmother. A quiet existence of calm and silence exists in this last room; Camera Aviae (Grandmother's Room), representing Moore’s grandmother's discarded corrugated sheet-iron lined house with its soft cracked earth floor. Two pieces of basic furniture appropriately appear in the room; a wire stretcher bed (a shearer’s bed) and a 44-gallon drum table. As with most of the installed rooms in this exhibition (other than the school space), which have been exhibited in other places and contexts, this space is a variation on the interior of Bennelong/Vera’s Hut at Bennelong Point for the 2016 Biennale of Sydney.

There are days, this is one of them, when you wonder, what your role is in this country, and what your future is in it? … From my point of view; no logo, no slogan, no party, no skin colour, indeed no religion, is more important than a human being.

James Baldwin, The Price of The Ticket, Californian Newsreel, 2009

Extensive recent research has revealed that the NIght Parrot still lives and is thriving, but its life is still in the balance. It is a similarly fragile combination of environment and care that underscores the postcolonial insights, and highly personal traces as subjective elements inscribed in the walls and niches to give this exhibition depth and strength. Curiously, Moore has described this acclaimed installation as a “funereal exhibition,” as though he’d died and this was his wake. He attributed this to the experience of anxiety as a form of death, which he has suffered from for some time. This exhibition based on childhood memories can be attributed to youthful alienation and a more current form of mid-life crises. If this is a death I can only wait to see the re-birth.