In Darwin earlier this year I heard the Barrister Sturt A Glacken QC describe to three judges presiding over a native title case how the Dreaming does not sit within a neatly bound time or place. It does not have a start or end. Tjungunutja: from having come together reminds me that the same can be said of history, and of art, and specifically the art of Papunya. The more you start to uncover the more factors you will find at play. There is a lot to be gleaned from this exhibition’s title—and the curatorial currents of Tjungunutja follow through, delivering a rigorous new account of the confluence that produced this art movement from the remote township of Papunya in the Western Desert.

Curated collaboratively with the Aboriginal custodians of this art movement the exhibition does away with the modernist myth of singularity – of a single person, of a single start, of a single vision. Together, Sid Anderson, Long Jack Phillipus Tjakamarra, Michael Nelson Jagamarra AM, Joseph Jurrah Tjapaltjarri, and Bobby West Tjupurrula, and Luke Scholes MAGNT Curator of Aboriginal Art Tjungunutja have created a revealing account of Papunya’s dynamic heterogenous beginnings. The many active players involved in this narrative include the Aboriginal artists themselves and an array of white supporters in administrative, commercial and creative capacities. Tjungunutja presents Papunya as a community grappling at the edges of new and uncertain intercultural boundaries that were not without conflict and unease, or for that matter vibrancy and innovation. Here different Aboriginal language groups and families congregated in new ways, and black and white Australia negotiated their relationships amidst the political transition from assimilation to self-determination. The Papunya Art Movement is the result of many factors having come together.

MAGNT’s collection of early Papunya boards is of indisputable significance. No other single collection of its kind can compare. The majority of these works, which came from the first four consignments Geoffrey Bardon sold to Pat Hogan at the Stuart Art Centre in Alice Springs between 1971–72, have rarely, if ever, been shown in full and without controversy. This is because many of the works contain secret-sacred material that despite various attempts over the decades has seldom been handled appropriately. How to show this work, if at all, has been a topical conversation since its first public exhibition in Alice Springs in 1974 right up to the present. It took six years for Bobby West Tjupurrula, current Chairman of Papunya Tula Artists and co-curator of Tjungunutja, to express his disquiet that there were works by his father in the AGNSW exhibition Papunya Tula: Genesis and Genius in 2000 that should not have been publicly shown.

With the Aboriginal custodians at the core of Tjungunutja’s curatorial process and the formal engagement of the Aboriginal Areas Protection Authority (AAPA) since 2012 the same discontent seems less likely to emerge. The very real potential for serious cross-cultural misunderstandings is evident in an account from Geoffrey Bardon in the exhibition’s catalogue. After one of the initial meetings with artists Tim Leura and Billy Stockman to establish a company for the artists at Papunya, Bardon noted:

I was amazed to learn that neither man had understood why I had brought them to Alice Springs, or what I said in the car, or of what happened in the solicitor’s office, or fully anything about the Aboriginal company.[1]

This, and the archival image of two men in a Haasts Bluff store featured in the exhibition’s film, brings to mind the charged dynamics of race and colonisation that inform all of this art and its history. These underlying factors are skilfully brought to the fore in subtle yet powerful ways by Tjungunutja, and particularly so in the film. Through extensive consultation led by AAPA 63 of the 226 paintings in MAGNT’s collection have been deemed inappropriate for public display. The exhibition has been produced from the remaining 163 paintings. All components of this collaborative curatorial process – extensive time, appropriate people, intercultural conversations, rigorous new research – point to an inspiring model of best practice. As perspectives shift, as other voices become empowered to speak, and cultural and political economies adapt, time will be the ultimate judge. Although to date, the curatorial team’s extensive efforts to get things right are working.

The exhibition space, with its darkened walls, on the ground floor of MAGNT feels like a quiet gathering where the public are able to “meet” the work, and by extension the artists and historical moment that produced them. This only heightens the overarching curatorial tenant of “having come together”, though seeing the black walls upstairs for the NATSIAA exhibition made me feel this was less of a curatorial choice and perhaps more of a practical one. It may be obvious but also worth mentioning that the exhibition acts as a reminder that art is what remains after people are gone. You can sense the artists knew this too.

In a separate viewing area is an 84-minute film, made up of twelve chapters, with each chapter focusing on one of the founding members of the Papunya Art Movement. If the exhibition is a coming together of the past through art, then the video is where memory lies in the present. Through this film, directed by David Nixon, we are able to hear directly from the artists and their families. The gentle pace and quiet detail builds a mood that speaks of what art means to Papunya. Not as a vague “Aboriginal community” but as a place made of individuals who grasped opportunities and expressed their worlds in a way that built a legacy their descendants still hold dear today.

The publication is the final piece of this tri-part curatorial effort. It is no doubt the part that requires the most mental exertion, but it is also where Tjungunutja’s full impact blooms. The use of Tjungunutja as a driving curatorial concept is grounded in the Aboriginal curators’ memories of ceremonies that took place just prior to the art making of the early 1970s. From a mess of social conflict produced by the displacement of colonisation and the intermingling of different language groups, this was a culturally competitive atmosphere of knowledge exchange that went on to inform the artmaking at Papunya. A conversation between the curators describes this with a startling clarity that immediately decentres the school and Geoffrey Bardon’s role as “sole initiators”. Instead, they are more accurately framed as one among a number of the movement’s non-Indigenous supporters. Bobby West Tjupurrula sets the scene:

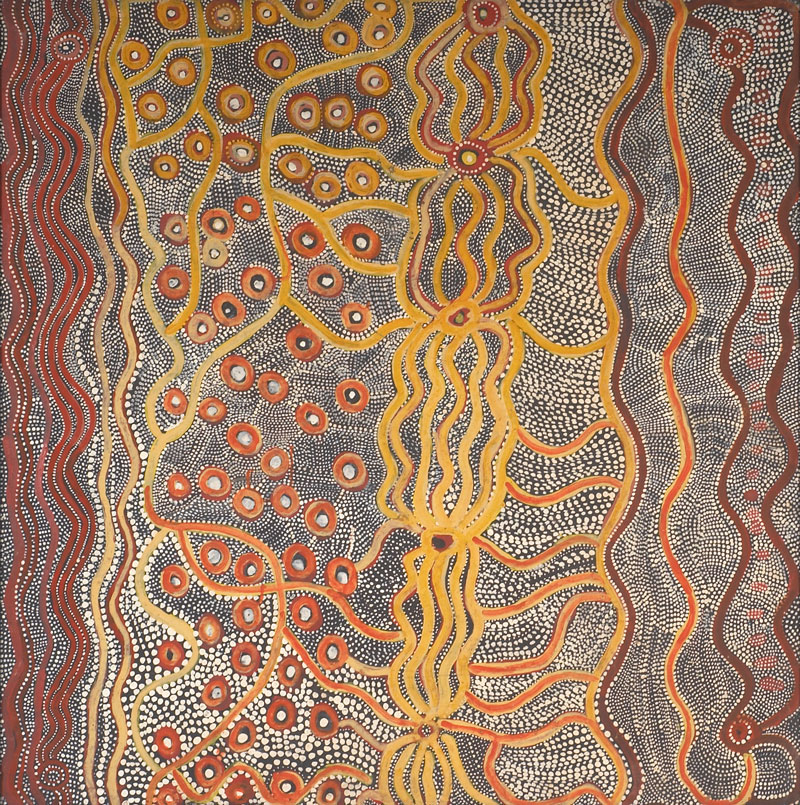

Pintupi people were having a hard time in Papunya. There was a lot of fighting, a lot of arguments and they wanted that to change. All the tjilpis [old men], it was their idea. The Pintupi men wanted to show people in Papunya that they had really strong law, Tingarri. They wanted to share it, teach it, because they were all together in Papunya and they wanted to show this other way, Pintupi way, Tingarri. They were giving it as a gift, that Tingarri. Warlpiri, Luritja, Anmatyerr, were watching, waiting for their turn … After that, after Tingarri, that’s when they did dot painting, body painting. Then they did that [Honey Ant] mural at the school, made it public, letting everyone know they were all together.[2]

.jpg)

In his catalogue essay John Kean describes Papunya as a multifactorial genesis and a ker kwaty (meat stew).[3] Ceremony is one ingredient, but so is the influence of the art and craft economies already well established in the neighbouring communities of Hermannsberg and Ernabella, along with the encounters with missionaries and government bureaucracy, and an engagement with comic books and American cowboy films. The artists’ new-found confidence for the expression of their cultural worlds to a white audience was further shaped by the shifting political dynamics seen in the dying days of assimilation and the dawn of self-determination. This complex network of influences and inspirations described by Kean, undoes the outdated idea of the cultural “purity” often ascribed to the early Papunya boards. Shaped by the displacement, economies and popular culture of colonisation Papunya is the result of a complex intercultural world coming together.

The story of Papunya’s Art Movement is a decidedly male world. In large part this has got to do with the artwork’s connection to men’s law. But another contributing factor to the reception of this work, as opposed to its production, could also be that the Euro-colonial world – Australia in the 1970s – was simply more comfortable with male artists, particularly in the realm of fine art. It is well known that in the field of anthropology much more has been written about men’s ceremony than women’s precisely because of the fact that most anthropologists were men. Bardon himself described supporting women’s craft in Papunya, and Ernabella had already been in operation for decades. So why was women’s creative work deemed as craft and not fine art? Was it simply because the intellectual worlds that informed women’s lives and labour were inaccessible to the likes of Bardon? Or that the historical times were so entrenched in the west’s reductive frames of fine art, craft and gender, that they were unable to see? There is another story to tell here.

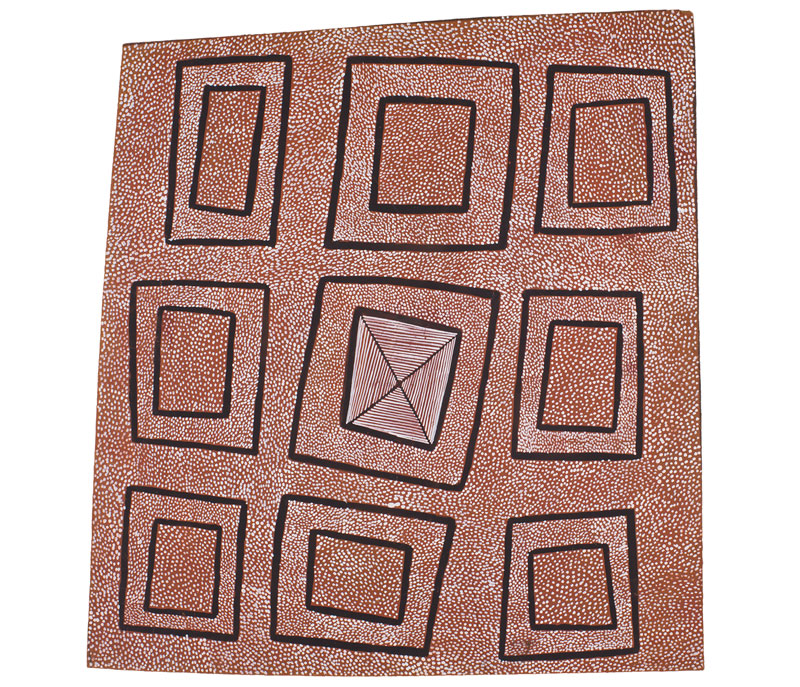

Yet what surprised me most about Tjungunutja was the similarity it brought to mind, both in terms of aesthetics and politics. What normally strikes me about Aboriginal art across Australia is its endless diversity. Distinct visual languages emerge from different regions, within these broad regions a plurality of languages and cultures creates even greater intricacies and within those communities each individual artist develops their own recognisable style. The density and bright colours of Western Desert art visually diverge from the more sparse ochre surfaces that characterise work produced in the east Kimberley, where I live. But walking through Tjungunutja I started to feel a sense of the familiar. In Kaapa Tjampitjinpa’s Wild Potato Story and Tim Leura Tjapaltjarri’s Yam story (night-time) I saw Miriwoong artist Peggy Griffiths’ bush cucumbers and Gija artist Mary Thomas’ bush potatoes. In Charlie Tjaruru Tjungurrayi’s Bush Tucker I saw shapes resembling Ngarranggarni (Dreaming) figures that appear in Mabel Juli’s lesser-known oeuvre. And in Charlie Tjaruru Tjungurrayi’s Water story I saw Miriwoong leader Paddy Carlton’s Lightning Men that adorn the logo of Waringarri Aboriginal Arts.

This is not to suggest any direct or concrete correlation or appropriation, but to highlight the cultural constants or connections that are not always immediately explicit. These resonances are informed in part by songlines, ceremony and trade—that tie together Aboriginal culture across Australia in very real ways. Another point of similarity was to be found in Scholes’ essay investigating the non-Indigenous players who contributed to the early Papunya narrative. Scholes’ research reveals an administrative scene that was not at all as unsupportive of the artists’ work and intentions as Bardon’s telling would have us believe. The essay also reads like a case study from Kim Mahood’s “Kartiya are like Toyotas”, a lacerating and influential essay on the systemic dysfunction of white workers in remote communities.[4] In short, the territorialism, lack of accountability, exhaustion, and miscommunications that are found in black and white relations in much of remote Australia. What surprised me in Scholes’ essay, was how this has been a constant for so very long. Why isn’t this improving? Perhaps, because very little is improving at all.

Throughout Tjungunutja there are frequent references to the assimilationist period and the transition to self-determination, which overlapped with the development of the painting movement itself. Under the Assimilation Policy it was assumed that Indigenous advancement depended on school attendance, training and compliance with regular working hours.[5] I need only look outside my home in the east Kimberley today to see this in operation once again, in fact I wonder if it ever really left. John Kean describes how the seminal leader and artist Kaapa, presumably shouldering the prevalent ideas of his time, would have expected his children to receive a better education and greater sense of empowerment than his own. Kaapa’s art, like so many others, became a tool to maintain his cultural identity for future generations who were receiving a western education. Yet Kean concludes that despite decades of apparent “self-determination” Kaapa’s children have not enjoyed the agency that he embodied.[6] The same can be said of so many in the east Kimberley too. The course of history is in no way a natural path to betterment.

Yet the Papunya Art Movement did shift something important, the consequences of which deeply inform contemporary thought in Australia. In his catalogue essay Fred Myers suggests that the power of early Papunya paintings lies in their resistance to Western categories of fine art or ethnographic object; they are at once both, visually powerful and culturally alive. Furthermore, he argues, they offer theoretical value in transforming – or at least participating in the transformation – of certain Western frames of knowledge.[7] Of these paintings, Myers explains:

They resist simple reduction to formal Western aesthetics, although they are aesthetically brilliant; they are an extension of the painters’ continued insistence for recognition of their claims to land, to place … a pursuit of sovereignty of sorts. Contemporary art – unlike the formalist modernism from which it emerged – does not insist that art remain within the boundaries of a frame.[8]

A pursuit of sovereignty in the most contemporary of forms, these paintings are an inspiring story of cultural assertion and economic opportunity in a difficult colonial world. Perhaps just as the artists intended, there is so much to learn in this for today. And like the painting movement itself Tjungunutja defies the frame.

Footnotes

- ^ Luke Scholes, “Unmasking the myth: the emergence of Papunya painting”, in Tjungunutja: From Having Come Together, Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory, 2017, p. 145.

- ^ Bobby West Tjupurrula quoted by Luke Scholes, “Unmasking the myth: the emergence of Papunya painting”, in Tjungunutja: From Having Come Together, Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory, 2017, pp. 117–18.

- ^ John Kean, “Framing Papunya painting: form, style, and representation”, in Tjungunutja: From Having Come Together, Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory, 2017, pp. 185–192.

- ^ Kim Mahood, “Kartiya are like Toyota”, The Griffith Review, no. 36 April, 2012.

- ^ Kean, p. 177.

- ^ Kean, p. 178.

- ^ Myers, p. 205.

- ^ Myers, p. 208.