University of Western Australia Art Collection, University Senate Grant, 2015. © Kevin Ballantine

The two current exhibitions at Lawrence Wilson Gallery, Kevin Ballantine: Photographs 1986–2001 and Here&Now17: New Photography raise important questions about the difficulty of representing Western Australia photographically. The very notion of representing WA is complicated by the inescapable void, or self-perception of a blankness at the core of the state’s imaginary. As Jon Hartley has argued, the cycle of “rush, defeat, and depopulation” that characterises modern and contemporary Western Australia has radically impacted the way we think about it qua representation and interpretation.[1] Hartley argues that the questions posed are not necessarily of the order of representation or interpretation, but rather we ask of WA “‘Is it?’, ‘Is there anything to look at?’, ‘Is there anyone to look?’”

While these questions do not flatter, they feel particularly relevant in the wake of the enormous construction and redevelopment projects that have attempted to enliven the state’s capital city. In order to make Perth a more vibrant destination for tourists, the new Arena, the Elisabeth Quay project, and the connecting of Northbridge and the city centre, feel like part of a project to eliminate Perth’s reputation as “Dullsville”.[2] While public space is almost entirely over-determined by capital – as the flows of investment channel or atrophy activity, and form our built environments – the impact of cycles of boom and bust seem central to the photographic works in both exhibitions. It is in this way that both Kevin Ballantine: Photographs 1986–2001 and Here&Now17: New Photography feel contemporary; both exhibitions address the problem of remaining faithful to a place characterised by vastness, absence, and transversal waves with their dramatic crests and troughs of activity. Ballantine’s exhibition is structured around work commutes, major spectacles driven by capital, such as the America’s Cup, and a sense of beauty encroaching on banality.

.jpg)

University of Western Australia Art Collection, University Senate Grant, 2015 © Kevin Ballantine

As Hartley has argued, spectacles like the America’s Cup are inseparable from the celebration of the quintessentially modern phenomena of mass movement – especially the movement of bodies. Hartley notes that, like WA itself, the America’s Cup is a celebration of the modern power to overcome distance – to make time and space plastic and amenable to the desires of capital. The movement required for a successful America’s Cup was not simply that of vehicles navigating immense spaces, but as Ballantine depicts across his works also included the movement of bodies in spaces that had hitherto been closed off to them. A more liberal attitude towards the use of public space and the circulation of goods and images was temporarily embraced, and rejected almost the instant the event had ended. Such relaxed attitudes to drinking, shopping, and public conviviality are reserved for special events in WA – the 2011 ISAF Sailing World Championships or the public screening of the Docker’s 2013 Grand Final, both in Fremantle, would serve as examples. As Hartley suggests, these events display not so much a reconsideration of the identities of places like Fremantle or Perth, but rather a means of drafting in “a cast of thousands, extras in the performance of modernity.”

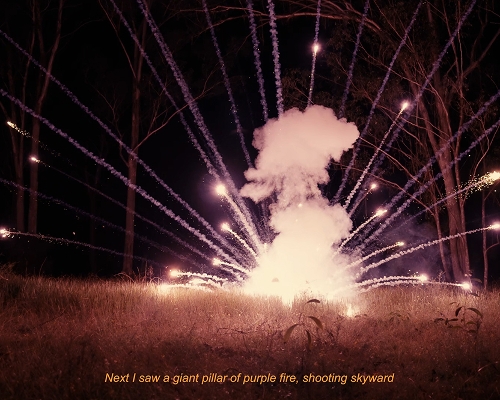

Ballantine’s photographs capture this sense of Western Australians as extras, rendered seamless and monochrome like mannequins. Looking no less staged than a Charles Meere painting, what separates the figures in Ballantine’s photographs from other mythic representations of Australiana is this quality of emptiness and stillness. This sense of bodies staged for spectacle is eerily made apparent through the juxtaposition of photographs of beachgoers and a shot of a shop-window display, featuring two headless mannequins adorned with “G’Day from W.A.” T-shirts. Here, Ballantine renders visible the paradoxical nature of WA’s upbeat but faceless reservedness. Shots of Fremantle show a city gripped by the enormity of a spectacular event, and of a place somehow too dispersed and barren to be graspable at all. In one particular photo, against a typically perfect Western Australian sky and coastal scrub, we find a billboard declaring “Our Cup Runneth Over”, an appropriate signal of the ambiguous relationship between emptiness and fullness that permeates Ballantine’s photographs. Full, but of nothing? Absent, and yet absent everywhere?

© Kevin Ballantine

Across the gallery, the works that stand out in Here&Now17, such as those of Dan McCabe, Lydia Trethewey and Scott Burton, engage with similar themes of abstraction, distortion, and a sense of emptiness that seems to evoke the precariousness of our contemporary relationship to space. As curator Chelsea Hopper’s catalogue essay explains, Dan McCabe’s acrylic sheeting and Alubond formal works are presented as abstract representations of the artist’s memories of “significant sites in Western Australia that resonated with him” on moving to WA four years ago. They are described as abstract due to the lack of “immediate site specificity or recognisability.” But these flat blocks of colour, as photographs of the material used for high-rise facades, do suggest specific sites. The recently built Perth Arena, Lord Street luxury apartments, and various other building projects across the city are constructed from just such flat, saturated, coloured panels. Alubond and Alucobond have become visually synonymous with the Barnett years of anonymous refurbishment that has given Perth’s contemporary skyline its facelessness. Contra the personal intentions of the artist, McCabe’s works speak directly to the site-specific non-specificity of Perth’s built environment.

Employing a radically different embodied aesthetic to similarly anonymous ends, Trethewey’s photographic and video work, incorporate solvent washes to produce a fluid and malleable distortion of urban and suburban spaces. Framed through the car window, Trethewey’s images manifest the seemingly endless production and reproduction of the suburban and outer-metropolitan sprawl of WA. This is particularly evident in her video work, in which the chronology of the car ride is disrupted by the stuttering aura (like a migraine) of the solvent wash effect. This spectrally haunting work, as a semi-translucent film, and conjures a force beyond the spatial environments depicted. Like global capital itself, unrepresentable except for the affects it has on the boom and bust cycles it engenders, the solvent washes disrupt the urban and suburban settings of her works without presenting themselves with a stable identity or cause.

Scott Burton’s photographic work invokes a similar sense of WA as formed and deformed by anonymous forces and flows. Burton’s photography conveys a sense of movement, whether it be of people travelling through semi-industrial zones or objects that suggest construction in the ever-present construction and repair of roads that so enrages Perth drivers. As with Ballantine’s work, Burton’s photography suggest movement without a sense of destination or direction, the seemingly aimless movements of commuters through carparks, major roads, and empty suburbs. In a recent interview, Burton comments on his love for suburbs like Innaloo, a nexus of giant shopping complexes, train and bus exchanges, as well as major roads.[3] He states that anyone who has tried to walk through the area will immediately grasp how little the pedestrian has been taken into account. The roads that connect discount liquor stores, cineplexes and enclosed shopping malls are treacherous to navigate by foot, being set up for vehicles to tear through and leave behind. Presented in the minute scale of Instagram photographs, Burton’s works present their subject matter and those subject’s worlds as indeterminately abstract. Are these fragmentary images of some meaningful place, or are these meaningful renderings of fragmentary spaces?

Accordingly, Here&Now as a comment on contemporary photography, usefully appraises the conditions for photography as determined in advance through certain models or images of production. WA is perhaps the perfect setting for such an investigation, insofar as it lends itself to a broader problematic of self-effacement in the increasingly anonymous spectacle of public life, encountered through forms of digital mediation, and determined by a drive towards further utility and productivity. Perth is precisely the kind of “nowhere” that one encounters “everywhere”. The questions that Here&Now provoke are maybe not those of the ontological status of photography, as curator Chelsea Hopper suggests, but more around the issue of the here and now in both the production and dissemination or transmission of photographs in the world of smartphones and Instagram. Questioning the ontological status of our relationship to the very spaces that provoked the production of images is, as Hartley might argue, primary: “Is it?” “Where is it? “Is there anything to look at? “Is there anyone to look?”

Footnotes

- ^ John Hartley, ‘A Political Theory of Progressive Individuals? Western Australia and the America’s Cup, 30 Years On’, Thesis Eleven 135(1), 14–33, 2016.

- ^ So christened by Lonely Planet in 2000. See: https://thewest.com.au/opinion/dullsville-it-was-the-slap-in-the-face-perth-needed-ng-b88358013z.

- ^ See http://takeawayspecial.squarespace.com/takeawayspecialpodcast/2016/5/22/episode-15-scott-burton-instagram-innaloo.