.jpg)

A + A Publishing, 2016, hardcover

“I’ve created the problem for you to solve” (Tim Burns, quoted by Helen Hughes).

As an object the book is just the right size for a small bag, roughly A5, hardcover, white text on black ground. The slab font title, centre justified M / INE / FIELD fills four-fifths of the cover with the left-aligned contents listed in the bottom fraction. The spine lists the author and title as A+a.p : MINEFIELD. By now, if you know post-1960s avant-garde Australian art, you get the code – it’s got to be Tim Burns. And, if the reference eludes you, the book is arresting enough to make you pick it up, opening onto a field of variable and disconcerting font sizes and greyscale photos. It’s a breath of small hope to see Australian art writing taking itself seriously, while also risking a relationship with graphic design to strike a note between readability and dissonance.

Tim Burns devises situations through which he can act to exploit whatever might happen. He's been doing so since the early 1970s. Minefield, the work of art that is the focus here, involved the random placement of improvised incendiary devices on a patch of ground, covered over with red earth from elsewhere. Edward Colless, as commissioning editor, opens with “Time Burns” in which he lays out the story of the work, establishing its temporal drama and conundrum as a provocation to writers and readers: “So, it’s 1973. The Mildura Sculpture Triennial was showcasing new experimental art in Australia, dubbed “earthworks”. But at dawn on the first day a frontend loader ploughed up and destroyed the most provocative installation in the show in the interest of public safety. By mid-morning all that was left of a work that occupied around four hundred square metres of ground was furrowed scars. What had been so dangerous?"

Colless plays with the site of a work of art as both empty and full (placing it in the context of the disappearance of the Mona Lisa from the Louvre), an aporia of the everything and the impossible: the mystic and other-worldly contract of a work of art that can “summon a[n] indescribable thing.” The mines were “improvised” (Helen Hughes tells us how in her essay). Colless is a lover of complex thought, and while some may charge this style with hyperbole, his deft care toward the force of language is something this reader appreciates for an ability to relay the mood with both insight and humour. According to Colless, Burns “deliberately did not keep a map while installing the landmines, interring them in the unconscious of the site as a malevolent, hidden plot – a contraption that was “live” but entombed and forgotten, and could only be excavated through its traumatic discharge.” The book notably ends with the book’s own bio-pic: “Resisting Arrest: Edward Colless Tracks Down Tim Burns.”

What a daredevil the frontend loader operator was: he who razed the site as a consequence of the curator's decision. What must he have been thinking? The artist was the only apparent victim, suffering third degree burns to his hands while installing the work, and, it is said that local residents threw stones at him in the street.

This is the first book published by A + A Publishing, an imprint of the rebranded Art and Australia recently gifted to the Victorian College of the Arts (University of Melbourne) and is notably tasked with the focus on a single work of art. Leaning on the networked and collegiate tone of the institution, it also supports a pleasing diversity of approaches. The writers of different generations include Donald Brook, the legendary don of experimental art (founder and co-founder of the Tin Sheds, and the Experimental Art Foundation) and a long-time supporter of Tim Burns; Edward Colless, the erudite editor and glue as overarching series and magazine editor; Justin Clemens, an academic, writer, philosopher–poet and child of the late 60s; Lucy Bleach writing as an artist with a focus on the earth as ground; and Helen Hughes, a curator–writer, with her contemporary take on the aesthetic theory of Swiss art historian Heinrich Wölfflin.

Hughes solved a personal art mystery for me: the analytical category-making school of thought being out of fashion in the 1980s era of post-structuralist, feminist Euro-philosophy, where I gained my critical legs and learned that art is most effective when encountered apart from its maker (not a thought I ascribe to now). According to this method, one asks not “What does it mean?” but “What does it do?” in the realms of cultural affect and action. That is, art isn’t a representation of anything; it is the thing itself, it acts. She writes a lithe and elegant essay, classically constructed to compare two works very different in scale, Cildo Meireles’s Cruzeiro do Sul and the eponymous subject of the book, wrapped around a shared world (munde) as a geographical zone of “south-to-south art history” (a move made popular amongst other Melbourne thinkers like Anthony Gardener and Nikos Papastergiardis), while also offering (and resisting) a “socialised global north” and an eastern Asian plot centred on explosive works.

Hughes’ task is to locate both works in geopolitically shared histories of colonialism and its resonant effects and affects: works “made by non-indigenous artists on indigenous land […] both structured by the immanent threat of an explosion.” This essay travels a lot of ground, including the narrative sequence of the decisions on the day supported by a cast of key players and institutional challengers. Like Colless, Hughes makes generous use of footnotes as extended writing space – scholia – the place in the text where volcanic connections are made.

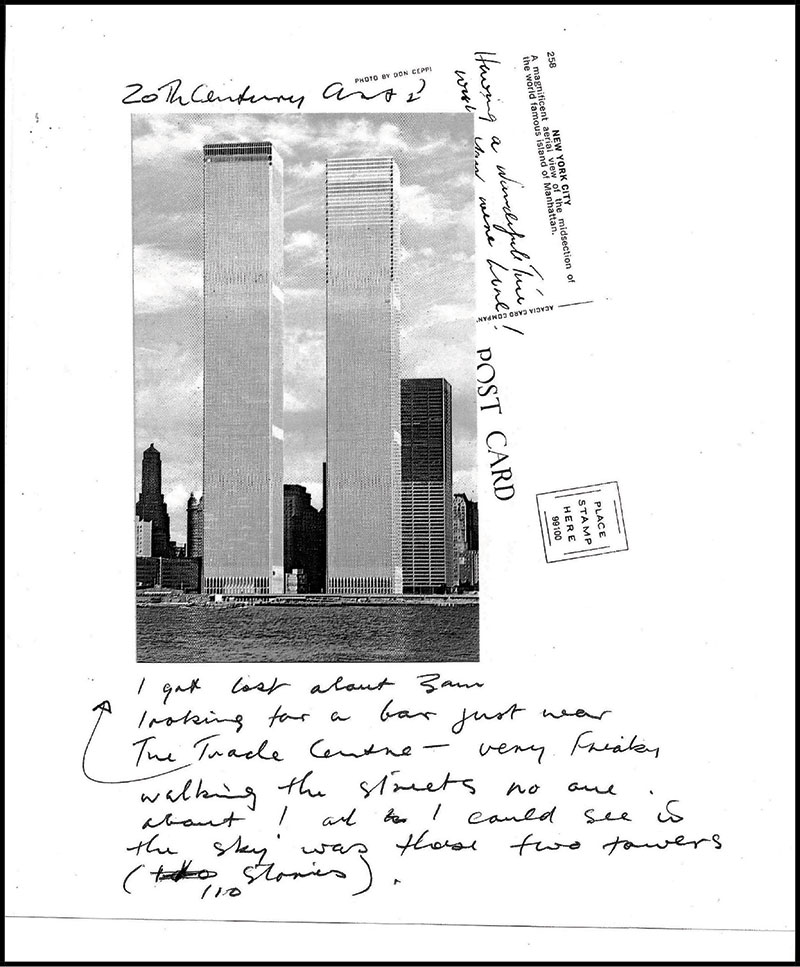

While Tim Burns was trying to get into the Factory (Warhol’s) in New York and taking still photos of the still-under-construction World Trade Centre, "Why Cars?" (1977), Justin Clemens’ father had moved his family to the British military base on Northern Cyprus. Clemens writes his piece in the style of the LRB (London Review of Books): that is, as a vehicle to tell a story of his own through a writerly and scholarly lens that dovetails, post-catastrophically, into the subject. Clemens’ terrifically told tale resonates beautifully with Burns’ dematerialised never-realised work by laying bare alternate temporal worlds of other possible scenarios to support the virtuality of actual events, the sensation, perception and emotion of the (im)possible.

Donald Brook gives the best bio-pic of Burns’ incendiary practice overall, putting the artist in a contemporary context, while supporting Brooks’ own somewhat difficult to comprehend distinctions between “art” and the “work of art” through visiting the hoary question of art’s ontological worth. I think I get what he means. Like many, I watched live-TV as the second plane flew into the South tower of the World Trade Centre. In the moment before I realised the sooty spots were in fact people jumping from mile-high windows, the affect–truth that set my skin prickling was This is art! Is this what Brook means I wonder? “This is art” rather than “the work of art”, art that skirts around the edges of meaning and markets and gets the indifference of beauty and nature, thereby resisting categorisation.

Geological slow time and tectonic shifts inform Lucy Bleach’s sculptural practice, and her take in “Underground” is to run with the inherent macho-destructive desire inherent in Minefield in a way that genders the very ground/earth. For Bleach, herein lies the explosion and the catastrophe; “It goes off – like a pop, like a laugh, a sneeze; like an orgasm; like a little explosion, an overflow. Its telling says, I am here.”

Bleach’s quote brings me to the unsung player in the book, the aforementioned typographic design by John Warwicker. The effect is to make thought a desirable material object, and the object an art work in itself. The font, all Helvetica and Swiss right-to-the-edges as body text with enlarged shouty excerpts, works to visually position the publication in a critical tradition (Germanic, like Hatje Cantz ). There are three ways to approach the text; the fast headline-grabbing run through, the slow careful and rewarding read, and then both together. The both-together mimics the dissonance of Minefield itself.

What can an art-publishing venture embedded in Australia’s most successful sandstone university deliver? Australian art writing and marketing are often barely distinguishable. Given the current climate of fear there is an urgent need for serious, playful, and difficult thought around visual art as a cultural strength beyond market forces. Why Minefield? Why right now? There are minefields everywhere, the real kind that decimate cultures and make the wealthy powerful. This little publication is a softly thrown gauntlet by A + A. It's not about the obscenity of real minefields, or Maralinga (although that is be considered too); rather, against the ground of the failed avant-garde project instigated by Dada and the Futurists, Minefield as a collection of dissonant thought is an appraisal of failure as a force. The installation Tim Burns assembled – razed before the actual event – has become a “work” over time and in this instance a cipher for an art world at risk, and of a particular mode of art and its discourse disappearing into fun, fact, and action leaving no time for reflection and slow thought.

Glorious images and objects are not the point here: visual documentation is minimal and sparse, forefronting the terrible beauty of grey. As Colless knows, the aura of a work of art still has resonance. It takes time to know what something might do, to recognise threads and implications; and at the same time, almost impossibly, one must live in the present. As Maggie Nelson writes in the Art of Cruelty: A Reckoning (2011) “to experience the dissonance – especially in art – one has to take the time, and leave open the divine possibility of being taken by surprise.”