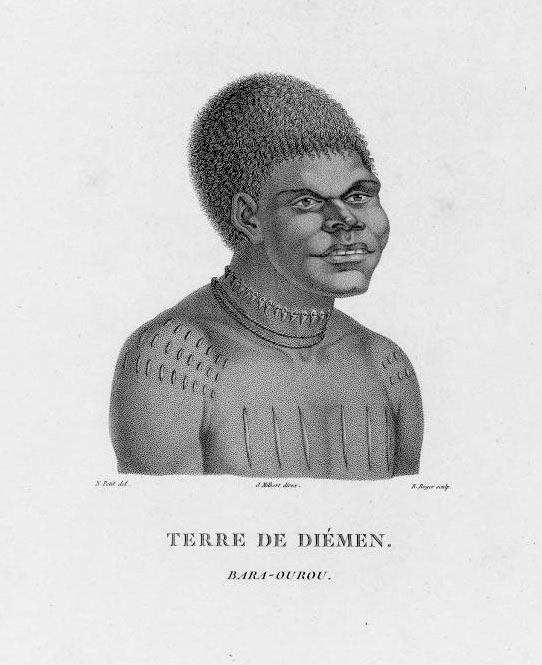

The Maireener shell necklace has been known to Europeans since their earliest visits to Van Diemen’s Land, as the island was known until 1856. Perhaps the best-known illustration of these encounters was provided by the artist Nicholas Martin Petit, travelling with Captain Nicholas Baudin in 1802. Born into a family of fan painters, Petit had been taken on as a gunner and draughtsman, but is thought to have been a student in the school of David.[1] His sensitive portrait of Bara-Ourou, jeune sauvage de la terrede Diémen, was first published in the atlas of the voyage in 1807.

The existence of these necklaces had been recorded by an earlier French expedition, when Admiral Bruni d’Entrecasteaux’s naturalist Jacques-Julien Houtou de Labillardière described a meeting with large group of Tasmanian Aborigines on 7 February 1793. During the interchange a young man offered the Frenchman a garland of shells that he had been wearing around his head. Curiously, none of the many portraits made by d’Entrecasteaux’s artist Jean Piron recorded these garlands. It might be concluded that they were not considered significant enough to note in the expedition’s visual record.

But it is clear from the various journals of Baudin’s officers that shell necklaces were encountered several times on the later voyage. Journal entries refer to a number of instances of gifting and exchange. Petit’s portrait, along with another atlas illustration, Terre du Diémen, armes et ornemens, by Baudin’s second artist, Charles Lesueuer, was instrumental in crafting the shell necklace as an emblem of Tasmanian Aboriginal culture in the imagination of early nineteenth-century Europe.

While the portrait of Bara-Ourou might provide an art-historical starting point for our understanding of the Tasmanian Aboriginal tradition of shell necklace-making, perhaps more importantly it also offers a unique key to appreciating the significance of its continuation. In 2010, the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery commenced a project to acknowledge and revitalise the tradition of shell-stringing. Luna tunapri (women’s knowledge), followed the success of the TMAG’s earlier tayenebe project, a celebration of Tasmanian basket-making undertaken jointly with the National Museum of Australia. Both projects commenced with a series of workshops initiated by Aunty Lola Greeno, who at that time was an Arts Officer at Arts Tasmania. These projects aimed to bring Tasmanian Aboriginal women together to discuss the history of important cultural practices, share stories of places, people and times, and to pass on their knowledge to younger women as future cultural custodians.

Tasmanian Elder, Aunty Patsy Cameron’s “King marina (maireener)”[2] necklace captures these objectives powerfully, and is one of the stand-out works in kanalaritja: An Unbroken String. Her creation of this necklace involved reaching back to the earliest image of a Tasmanian shell necklace to not only explore its unique materials, but to also take the bodily journey of finding, collecting, preparing and crafting these particular shells into an object that transcends time and change in Tasmania since European invasion.

The ability of Tasmanian Aboriginal people to draw from early European records in order to revitalise past cultural practices has proven central to a number of projects undertaken by TMAG in recent years. In addition to tayenebe, which reawakened a “sleeping” tradition of basket-making,[3] in 2007 TMAG has hosted a project resulting in the creation by Tasmanian Aboriginal men of tuylini, a traditional bark canoe – the first known to have been made for over 170 years. This project drew inspiration and technical knowledge from a small model of a canoe made by Aboriginal people during their forced exile at Wybalenna on Flinders Island, following an attempt during the 1830s by the Van Diemen’s Land government to exterminate them from the mainland of Tasmania in order to make way for colonial development.

Included in kanalaritja are a number of necklaces from this turbulent period. Unlike the necklaces recorded by the French, which were collected as ethnological specimens, Wybalenna necklaces became increasingly valued as commercial trade items, produced by Tasmanian Aboriginal women during their detention and sold at markets in order to supplement the poor rations provided by the government. This necklace production continued after the closure of Wybalenna in 1847. Aboriginal women who had learned their skills prior to colonial impact passed on this knowledge to their children, creating shell-stringing communities on the islands surrounding Flinders, and returning the practice to the mainland of Tasmania.

During this period, and especially on the small island of Cape Barren where a reserve had been established, Aboriginal matriarchs maintained and diversified shell-stringing. While necklace trade continued to provide a valuable income supplement, the Stringers were also crafting and expressing individual and filial identities with their necklaces. A wider range of shell species was slowly integrated into their stringing. As the practice was passed to succeeding generations, makers and families became recognisable for their favoured shells, selected for colour, pattern and shape. Shell-stringing came to express genealogies, as well as cultural resilience, innovation and survival.

The many women whose necklaces are presented in kanalaritja are the inheritors of this history. Their involvement in luna tunapri builds and strengthens these family connections and at the same time reinforces connections to Country and place. While some shells are common to many coastal locations in Tasmania, others such as rice shells and maireeners occur in many varieties of size, colour and pattern – expressing the localised characteristics of particular islands or individual beaches. Often the source of specific shells is a closely guarded secret, passed on through families as a gift just as precious as the beautiful necklaces that they comprise. The palette of colour available between rice shells from different locations is beautifully expressed by pakana tunapri luna ningimpa (Coral Dreaming), a necklace of 1,600 shells by Vicki-Laine Maikutena Green.

This specificity to location also makes the tradition vulnerable to change. Coastal development in populated areas can affect access to beaches, with sewage run-off or infrastructure works easily upsetting the delicate ecological balances within which each species of shell flourishes. An even more ominous threat comes from climate change. Rising sea temperatures are already affecting the abundance of certain seaweed, upon which some shell species depend for survival.

Anyone can put shells on a piece of string, but to do it in a cultural way, following cultural practice, that’s a different thing.

Jeanette James, 2015

As any shell stringer will tell you, collecting and making necklaces is as much about the sharing of stories as it is the crafting of a cultural object. Kanalaritja includes tantalising insights into the profound strength of orally-based culture with each of the exhibition cases screen printed with quotes from the makers, as well as the more usual object descriptions. These enable the visitor to take a quiet, but privileged place in the circle of culture that surrounds Tasmanian Aboriginal shell necklace-making.

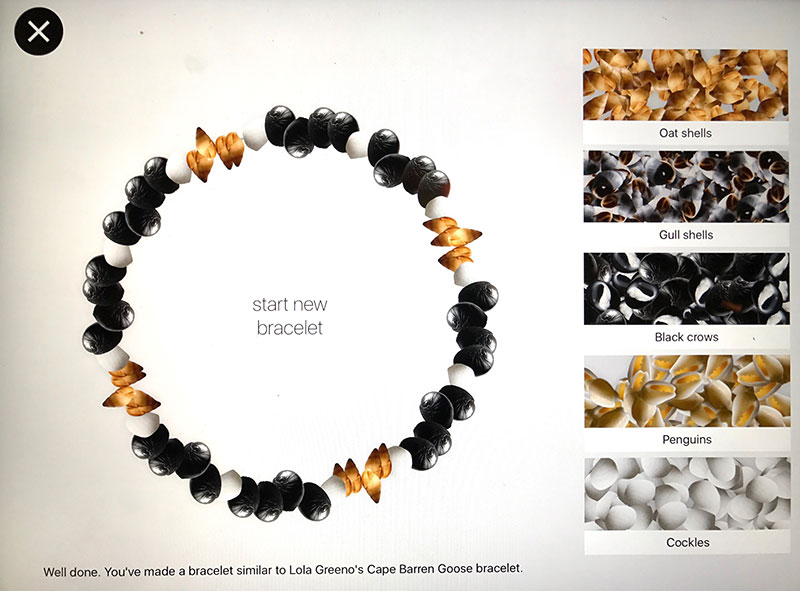

The exhibition also offers an opportunity to create a necklace. Through the ingenious development of an app, visitors can select from a range of different shell types, and arrange these in a sequence of their choice

There is little doubt that kanalaritja will meet with critical acclaim as it tours nationally over the next two years, courtesy of generous support from the Australian Government’s Visions of Australia regional exhibitions funding program. Curators Zoe Rimmer and Liz Tew (who also contributes as a maker) have captured the strength and vitality of luna tunapri that underpinned the success of TMAG’s previous tayenebe touring exhibition and translated it into a long-overdue definitive project on one of Australia’s most distinctive cultural treasures.[4] The result is an elegant and immersive project that also includes a beautifully designed catalogue and website taking readers into the history of the tradition and the lives of some of the women and their families who have carried this practice across a challenging period of Tasmania’s recent past, and into a vibrant cultural future.

Footnotes

- ^ Jacqueline Bonnemains, 'Biography of Nicholas-Martin Petit', in Jacqueline Bonnemains, Elliott Forsyth, and Bernard Smith (eds.), Baudin in Australian Waters: The Artwork of the French Voyage of Discovery to the Southern Lands 1800–1804, South Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 1988.

- ^ The kanalaritja project utilises spelling of some Tasmanian Aboriginal words according to the palawa kani language retrieval program developed by the Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre. Some of the makers involved in the exhibition choose to use other spellings, based on earlier historical records. Maireener is a word in use by Aboriginal people to refer to Phasianotrochus spp. shells prior to the palawa kani program.

- ^ During the lead-up to luna tunapri, necklace and basket-maker Verna Nichols described the practice of weaving as ‘not lost, just sleeping’. See http://www.tmag.tas.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/66770/tayenebe_education_resource.pdf (accessed 28 January, 2017)

- ^ The kanalaritja catalogue joins the monograph: Lola Greeno and Julie Gough, Lola Greeno: Cultural Jewels, Object: Australian Design Centre, Surry Hills, NSW, 2014, as key publications on the subject of Tasmanian Aboriginal shell necklace-making.