Early in the morning in Queenstown, I switched on the small AM transmitter I'd been handed by one of the members of the Unconscious Collective and, sure enough, amongst the fluttering hiss of static, paralleled by the thundering rain that was drenching Queenstown, I could hear voices and sound, sometimes indecipherable. The temporary radio station 7UN was working, and the signal was drifting all over the peculiar geography of Queenstown, an invisible ripple of sound and story that hovered above the festival like an electric ghost.

The Unconformity is the re-branded Queenstown Heritage and Arts Festival, a biennial event that does what it says on the label: it combines art and heritage that explores and celebrates a town. Queenstown is a mining town that sits at the bottom of a long and winding road that cuts through the fabled Tasmanian World Heritage area, and was once noted for the extreme pollution that had totally denuded the hills. Things have changed and the vegetation is returning. The mine that economically supported the town is not currently open and Queenstown’s future is anyone’s guess.

The festival in 2014 was successful, briefly swelling Queenstown’s population and giving the town a financial injection. In 2016 there was a branding change to The Unconformity. An unconformity is a geological anomaly where different eras of geology interact producing a visible collision of time. It’s a fair name for a festival that celebrates a place as strange and wonderful as Queenstown. Most of the residents are miners and they do it hard, but it’s more complicated than that.

The Unconformity was intense. It was a four-day event crammed into two-and-a- half days and it rained biblically for much of that time. This is quite normal, and the administration of the festival expected it, so they were well-prepared and most events took place under cover. Queenstown is one of the wettest places in Tasmania. Gumboots, raincoats and jumpers were mandatory, and the wet weather dampened nothing. If anything, it added to the feel of the festival and underlined it’s inherent difference as an event. The Unconformity is not about lazing in the sun and languidly taking in some entertainment. It was as demanding as life in Queenstown itself.

The Unconformity kicked off on Friday evening with The Rumble. Tasmanian composer Dylan Sheridan concocted a bellowing sound work to accompany crawling vehicles and managed to coherently integrate it with the sound of the machines: their engines and any sounding devices they had. The result was loud and long as the trucks and engines manoeuvred into position, their lights monstrous in the evening dark. But it was more than just a show of industrial might.

Some trucks carried things, encouraging a deeper interpretation of the whole event. There was an immense hollow log that had delicate ferns literally growing on and within it. Another vehicle carried what looked like damaged and mud-encrusted mining equipment. Both of these were expertly lit, and thus unavoidable in their contrast and narrative of endings and renewal. The thunderous sound was lent a melancholy edge by this clever presentation, and the question of what was being celebrated hung in the air with a surprising poignancy. What happens when mining ends? What happens to people, and to the land they live and work on?

The best of the art that The Unconformity presented tackled this question head on. It was surprising how much honesty existed in the art. Queenstown is a real place, with real challenges to face. Art that glosses over this would simply be bullshit, and while I can’t really speak for the people of this hard west-coast town, it’s very easy to see why this is welcome. An intensely frank look at Queenstown came with the film How to See Through Fog, made by Thomas Hyland, Glenn Richards and Sean Fennessy. The film was attended by a packed audience of locals who filled a hall at St Joseph’s, a small Catholic school decorated with rough but sincere murals of Jesus Christ.

The film looked beautiful. Queenstown locals told their story of the town and the closing of the mine, the previous festival in 2014 and the victory of the Queenstown Football side in the Tasmanian state league. Basically, it presented the truth that the town is economically challenged, while finding resilience and even joy in the people themselves. The narrative had emotional power and the cinematography was notable for its pacing and clever grammar, dwelling on faces and tiny details in silence to underline the content. How to See Through Fog was a stand out moment of the whole festival.

There was of course too much to take in over three days. One had to pick and choose and perhaps that was the point; finding what you needed to see, exchanging notes with other festival attendees and submitting to the conditions. This was where the Unconscious Collective’s radio project succeeded; it was everywhere for the entire festival, constantly in the background and available wherever you could find an AM receiver.

Gorgeous valve radios were positioned around the town, and small receivers were given away, so 7UN was subtle but apparent and consistent at all times. I found myself simply listening to the signal, whether I could truly discern the content or not, and the way everything drifted around and seemed affected by geography and weather was fascinating. The broadcasts were haunted and otherworldly, meshing beautifully with the odd geographic feel of the location. Interviews with locals and artists, sound art and short documentary all featured, as did a gloriously raw commentary of the festival’s football match. The Unconscious Collective made elegantly subliminal art that gave everything a quiet interconnectedness.

Sound art was also the focus of the Flux event, presented by Liquid Architecture. This event, perhaps unwisely, was sited in a former quarry, which had been sort-of landscaped and managed to have the feel of a secret garden, surrounded by soaring walls, filled with ferns and picturesque trees, and even featuring a pond. The setting provided an alluring backdrop but the foul weather challenged the performers at times. Nevertheless, there were sublime moments: from Dylan Martorell, whose clicking and popping analogue devices and general feel of home-built invention provided an engrossing performance; Brendan Walls played a dense, shimmering percussive set then handed out wax paper boats with tiny sound players to the audience for them to launch into the pond; Douglas Kahn delivered a fascinating lecture about climate change and the Hobart-based experimental band Omahara played a suitably massive rock-derived piece that went down well in this location. Evening performances at the quarry were lit by Jason James, who took full advantage of the location.

There was a surprising amount of visual art to be taken in alongside and around scheduled performances and events. It seems that Queenstown has a very active arts community. The Art Trail event took in over twenty local artists (not bad for a population base of about 1,800 people) and a range of existing gallery spaces and window displays. The sheer range was extraordinary and interesting, and the general standard of work was high.

Some artists did stand out for me: Ivan Stringer, who has a long-established gallery space, Art Frontier, on Orr Street in the middle of town has an angle he’s pursuing with some determination that explores landscape painting with a high degree of irreverence, although that is not the only string to his bow; there’s also his dedication to a kind of psychedelic-primitive surrealism. Across the road, in an old bank, some new arrivals in town bought some classic street artists from Victoria for the festival; the installation by Suki and Be Free was a delightful surprise to encounter at the new Q Bank art space.

.jpg)

Around the corner on Driffield Street the Denise Mitchell studio Gallery had a great number of competent and interesting West Coast Artists, but it was David Fitzpatrick who really stood out here. Fitzpatrick is a former miner who turned to art in later life, and his work, a mixture of ceramic construction and found objects, are clever reflections on that working life. His small exhibition of objects came together as a narrative, and there was a pleasing marriage of skill and intention in the work.

LARQ space, which the renowned Tasmanian painter and printmaker Ray Arnold has lived in and run for a decade, featured superb local work from Danielle Fairfield, whose technically impressive pencil drawings were surprisingly engrossing, and the very exciting photography of Marc Pricop. Pricop is clearly at the beginning of his career as an artist, but already exhibits a strongly defined eye. His images of his life around Queenstown – the place itself and his friends – really stood out for the competency and strong decision-making in the images.

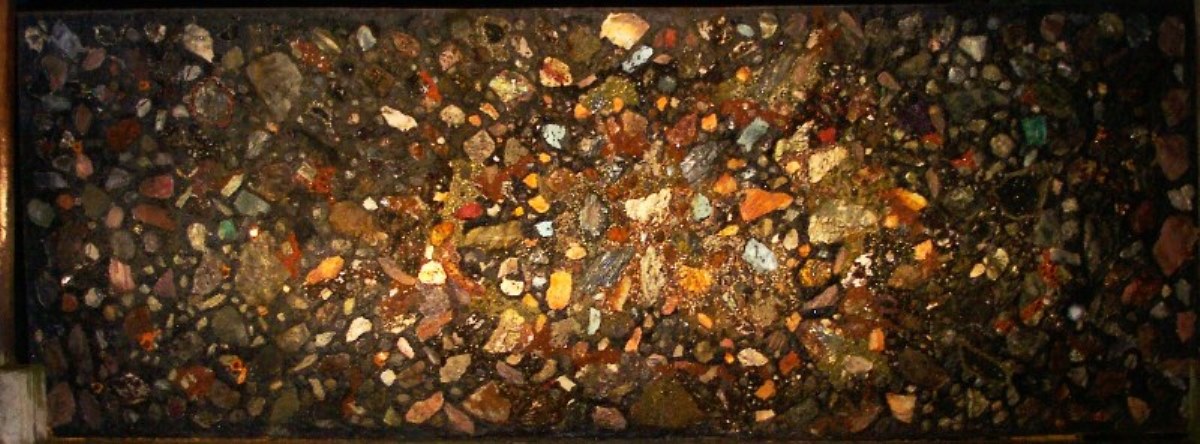

But the best treats in the visual art stakes were two complete surprises. Rory Wray-McCann, a life-long mine worker who has been involved with the industry in Queenstown and across Australia for most of his life, has translated this experience into a remarkable and singular art practice. To encounter his work, we had to board a bus and be driven out to his property, twenty minutes out of town. Wray-McCann has collected minerals and crystals from all over Australia and made massive, metres-tall pictures with them, the best of which are stylised images of outer space. The works have a physical density that makes them almost overwhelming. An eye may be caught by a single beautiful mineral crystal, but there’s an entire massive work that is astonishingly engaging. These works take anywhere from two to thirteen years to make, resulting in unique and special art that is almost it’s own genre.

UK artist Lindsay Seers has been to Queenstown before and made vital work from her visits, but her latest work Suffering is an experience that is almost unprecedented. Seers, with the assistance of Ray Arnold, has made this work about the now-deceased Queenstown resident Leo Kelly. Seers has trod carefully and made a humble and admirably respectful work in homage to this man and his art. She constructed a small tin hut, made from a characteristic type of corrugated iron, and placed small benches in it to encourage people to sit and watch a film in which Kelly may be seen, his voice heard, the interior of his home revealed, and (most importantly) his art seen. Kelly’s painting was an expression of his deep, committed religious faith.

After seeing the short film, one then encounters Kelly’s paintings – his entire output as an artist – and some relics of his encounters with faith. Kelly found rocks and saw the holy Virgin and more in them: these are lovingly preserved and presented as gifts from God. But it is Kelly’s paintings that truly astonish: Kelly was clearly untrained, and possibly hadn’t seen much art, but his strong personal faith is clearly expressed in each and every work. Kelly saw celestial lights and was a visionary. He is raw, but this it not outsider art. He was a private person, who lived in Queenstown all his life, and was well-known about town. It is not entirely inappropriate to compare him with William Blake, the great English poet and painter, for his work is the translation of religious ecstasy and unshakeable belief.

Kelly’s work is the kind of art one hears of, but is highly unlikely to encounter. It is evocative and potent, and seeing it at this festival felt like a remarkable privilege. It is hard to avoid the hyperbolic response here, but Kelly’s work and Seer’s sensitive presentation made for a memorable experience. It was the highlight of The Unconformity for me. It also captured the focus on the people of this strange, beautiful mining town and the powerful sense of community.