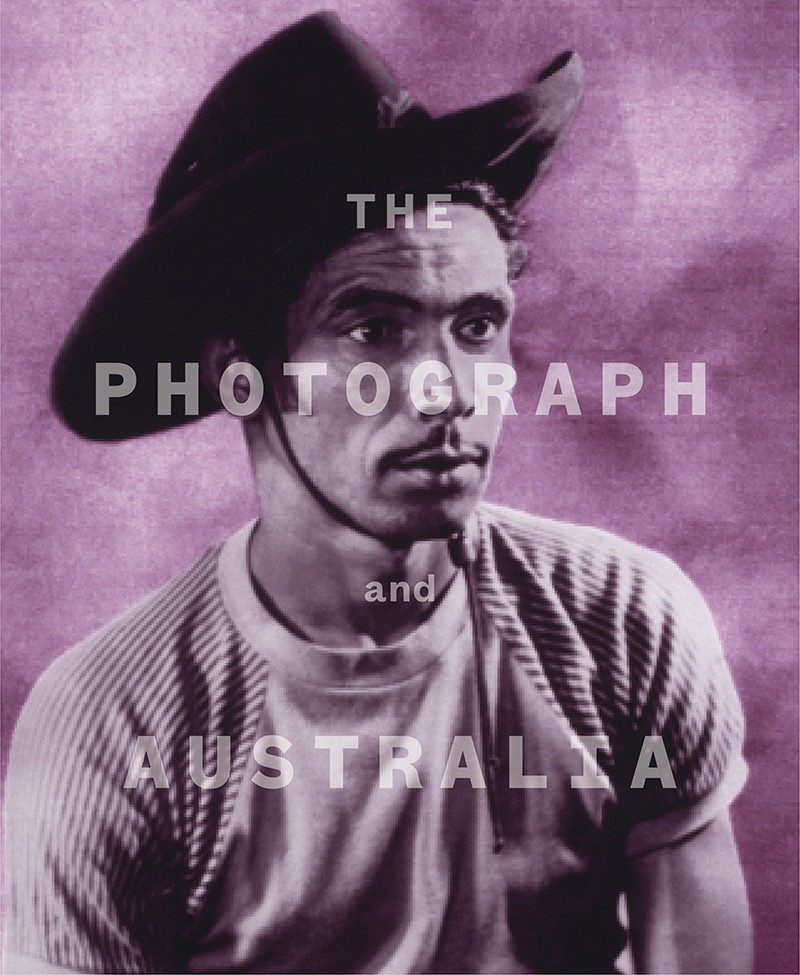

The 2015 Art Gallery of New South Wales' exhibition, The Photograph and Australia, was a great thematic sweep of Australian photography where memorable images from the past and present worked in conjunction to support a curatorial argument that photography has served to define the country and the culture that we call Australia.

The book of the same name, also published by the Art Gallery of New South Wales, cannot in all honesty be called a catalogue, even though it contains a record of the contents of the exhibition and reproductions of the works. Annear, with her fine visual sense, is very aware that it is simply not possible to replicate the visual impact of an exhibition within the pages of even the most handsome book. So she has not tried. Instead, she has undertaken the equally daunting task of producing an analytical account of the historiography of photography in Australia.

Because photography in Australia has only been the subject of curatorial scrutiny since the mid-1970s, the pioneer curators are still alive. Annear knows she is standing on the shoulders of giants and pays due homage to these scholarly curators, especially Gael Newtown in the 1970s, who persisted against remarkable odds at the Art Gallery of New South Wales before moving to the National Gallery of Australia in Canberra. The indefatigable Alan Davies at the State Library of New South Wales, Helen Ennis at the National Gallery of Australia and the more theoretical Anne-Marie Willis are all given their due. Two curious omissions in this pantheon are Jenny Boddington, the first curator of photography at the National Gallery of Victoria and Ian North, the inaugural curator of photography at the National Gallery of Australia.

As with the exhibition, the division of the book is thematic rather than chronological. The divisions - time, nation, people, place and transmission – are more controlled than they were in the exhibition as images are marshalled to support text. There are also complementary essays from Daniel Palmer, Michael Aird, Jane Lydon, Kate Davidson, Martyn Jolly and Geoffrey Batchen. These add colour to the argument of the interconnection between photography and our national self-identity.

Michael Aird’s essay, 'Early Queensland Photographers and their Aboriginal Subjects’, gives surprising context to the well-known heavily styled photographs by J.W. Lindt, Charles Kerry and Henry King. If the people in these photographs look similar, it is no surprise as they were all members of Archibald Meston’s performing troupe whose Wild Australia Show was a white man’s fantasy of Aboriginal life. This is contrasted by Jane Lydon’s discussion of Aboriginal communities who became active participants, working with photographers to record their lives, ensuring that they were represented in a respectful manner.

One big difference between the book and the exhibition is how images are scaled. The exhibition (appropriately) presented original photographs. There was no distortion by enlargement of historically important images. This was all cleverly managed by a salon hang. The book has no such constraints, which is why Mervyn Bishop’s photograph of Gough Whitlam with Vincent Lingari, one of the most historically important Australian photographs of the 20th century, is given pride of place in the frontispiece. In the exhibition its importance retreated on a crowded wall.

There is a sense of a photograph being a frozen moment, a fragment of the past caught in the present: from the very first portrait photographs to Ricky Maynard’s wistful images of northern Tasmania and Rosemary Laing’s structured/constructed photographs of an upturned suburban house. Annear links Roland Barthes writing on the sense of being photographed to the Ngarrindjeri people’s response to Charles Bayliss photographing them on the Darling and Murray rivers. The response of the subject to the photographer can cross culture as well as years. Art historian Daniel Palmer complements this observation with a riff on the nature of photographic self-portraits, from colonial days to Sue Ford, with a cheeky nod to modern selfies.

One of the fascinations of photography is that it changes with our understanding of its possibilities. Although photographs are often seen as a record of an event, these records are never impartial. There is also an immediacy in photography, as through these images of the past can also become the present. As Annear says, photography belongs to "a nether world of being and not being, legibility and opacity". Read this book, look at the images and enter a magical time machine.