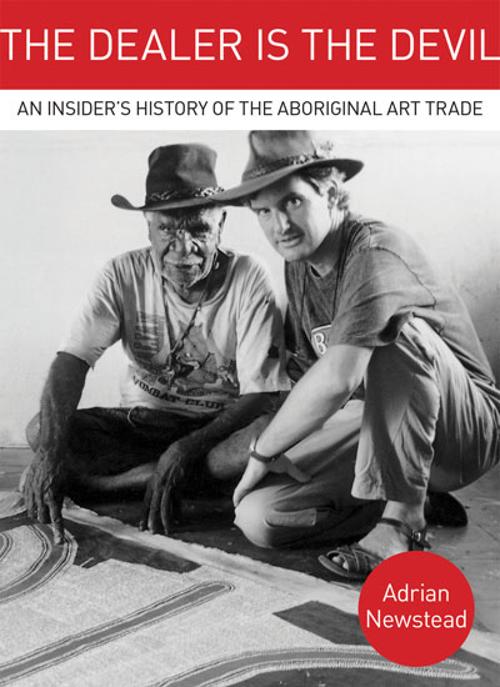

You can’t be involved in Aboriginal art in Australia whether as an artist, audience, reader, collector, curator, writer or other without beginning to get to know a certain group of people whether by reputation or in the flesh. Like any art or field of knowledge from philosophy or fashion to bushwalking or gardening, the other people who share your interest become a family of sorts (a broad extended family) and as I tell people (when expanding on this theory) – you don’t expect to like everyone in your family, nor can you expect them to like you.

To extend this family idea, Adrian Newstead is the slightly dodgy uncle who gets around, while you may not have met him you know who he is and hear of his exploits with amazement. Newstead’s book The Dealer is the Devil, eight years in the writing (and assisted by editor Ruth Hessey), tells an enthusiastic and detailed story of his long involvement with Aboriginal art, and thus necessarily mentions many people, including more than 400 artists. In so doing it reminds you afresh that art is about relationships with people and places as well as coloured surfaces and stories. He includes many rich and revealing accounts of his experiences with Aboriginal artists and the trade in Aboriginal art as well as personal details such as his father, a hairdresser who was Permanent Wave Champion of the World, telling him (on the back of his own disastrous experience) never to sue anyone.

Coming from a fairly typical Australian hippy background Newstead established Coo-ee Aboriginal Art Gallery in 1981 and has been on the ground in the promotion and selling of Aboriginal art for over thirty years, and still is. The Gallery started as Coo-ee Emporium “at the seedy end of Sydney’s Oxford St, Paddington” selling art by Australian artists and craftspeople. Its first Aboriginal exhibition was for Tiwi Design of Bathurst Island. In the course of many adventures, moving from the bottom to the ‘top end’ of art selling, Newstead worked for the auctioneer Lawson-Menzies as Head of Aboriginal Art from 2003 to 2008 gathering work for specialised Aboriginal art auctions.

The book begins with the intrepid Newstead driving from Sydney to the Kimberley with a car full of prints by Rover Thomas, Queenie McKenzie, Jack Britten, Hector Jandany and children of Warmun to be signed. The car is stolen “hot-wired by petrol-sniffing teenagers”, four boxes of the prints are recovered, then incredibly he finds some from the last box floating in the Mary River, retrieves them, dries them and gets them signed. This is taken from his diary of 1998. And on it goes. Newstead travels often, driving from Sydney to the middle of Australia, and has many stories of artists sitting around campfires in his backyard in Bondi.

As its subtitle states The Dealer is the Devil is an insider’s story spilling the beans through providing background and details to the many complicated ways that Aboriginal art has been made, bought and sold over the years, about politics, the Aboriginal Art Board, how reputations have grown and waned, the curious ways in which provenances are made and devalued, the power of personality and points of difference, what carpetbaggers are, how auction houses and arts centres work or don’t work, how newspaper articles can influence events – it is a gripping tale.

The Dealer is the Devil is neither art history nor theory though it sketches in some of the deep origins of Aboriginal culture, but a breathless personal history, though not a strictly chronological one, of some truly amazing times in art in Australia. The birth of a new genre in art, even though it is connected to the oldest living culture in the world, does not happen very often. It is Newstead’s strong appreciation of the art and the relationships he and his family have with many artists which form the bedrock of the book rather than the making of money which is what dealers are often reputed to be most interested in. Newstead seems to have worked quite hard for his money and for him being a dealer is a lifestyle, or rather a lifework, not simply a cashflow arrangement. Yet the sometimes mysterious and complex nexus of art and money is a strong thread in the book.

Newstead points out that Richard Bell’s 2003 Bell’s Theorem: Aboriginal art it’s a White Thing forced him to write the book as he disagrees so strongly with Bell’s wholesale demonisation of white people in the Aboriginal art trade. He believes it to be a “two-way street”.

If you are interested in Aboriginal art and know some of its characters you will enjoy reading this book. Newstead’s enthusiasm for Aboriginal art is informed and stimulating, and the art is a never-ending story.