In 1988 Djon Mundine was responsible for bringing together the collaboration that created The Aboriginal Memorial, that spine-tingling installation of 200 grave posts by Ramingining artists that greets visitors to the National Gallery of Australia in Canberra. It is a reminder of both the continuing ancient traditions that govern the land, and the grief that Aboriginal people feel for their displacement. It was appropriate therefore that Mundine be approached to be the curator for an exhibition to honour Bungaree, the most successful of all the Aboriginal negotiators in the years after the convict colony was first established at Sydney Cove.

Bungaree was the joker, the man who could mimic the new overlords, but also work with them so that in 1802 he travelled with Matthew Flinders on the Investigator, on the first ever circumnavigation of this country. Flinders was the man who first called this country "Australia", so Bungaree became the first “Australian”. There was a moral imperative for this exhibition being hosted by the Mosman Art Gallery. In 1815 Governor Macquarie granted Bungaree land at George's Head on Sydney Harbour. His descendants lost the benefit of this when the army took over the land for fortifications in the 1870s and it is now a part of Sydney Harbour National Park, next to the priciest real estate in the country.

John Cheeseman and Katrina Cashman (Mosman Gallery’s director and assistant director respectively) have responded to the special debt owed by their community to the descendants of the survivors of the first encounters. With Mundine’s help they supported a group of urban Aboriginal artists - some well-known, some without any significant public profile, some young, some older – and, through a series of intensive residential workshops at Chowder Bay, all came to know about Bungaree, his legacy and their place as his cultural heirs.

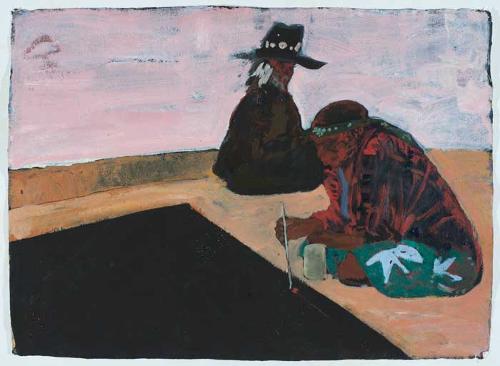

The result is a truly remarkable exhibition that helps explain the cultural riches that have been released by post-Apology Australia. These artists are all interrogating the way their ancestors reacted to the coming of the strangers. The most exciting works are not from the most obvious quarters. Fiona Foley, Gordon Syron, Gary Lee, Daniel Boyd and Danie Mellor have fine works that fit in with their standard repertoire, no surprises here. But Peter Yanada McKenzie, who is best known for his documentary photography, has produced a series of sensitive silhouettes, quoting portraits from colonial times, a sculpture of boomerangs as made by his people of La Perouse and a ballad, sung in a mellow country and western voice – “The strangers never said sorry”. The other veteran photographer, Mervyn Bishop, has worked with his son, the dancer and actor Tim Bishop, to create a witty tribute to the many personas of Bungaree as he clowned his way through contacts with the white people. This enabled him to both survive the catastrophes of invasion and to lead his people towards a workable accommodation with the unfolding future.

The real revelation though comes from the younger generation. Caroline Oakley’s sensitive watercolours of Bungaree and his family are reproduced in the catalogue, but her most memorable works are of costumes she made to honour Queen Gooseberry, one of Bungaree’s wives. She uses silhouetted forms and textile collage to evoke the assertive nature of this great figure of early 19th century history.

Lynette Riley and Diane Riley McNaboe’s giant possum skin Thubba-ga Cloak, with designs incised in pokerwork, dominates the upper floor while Warwick Keen revisits the subject matter of the 1988 Ramingining grave posts, while looking for the ghost of Bungaree in the glades and caves of Mosman’s bushy foreshores. Leeane Tobin’s installation manages to evoke the desolation of Bungaree’s generation as they came to realise what they had lost. Bungaree’s tactical collaboration led to him being regarded as a traitor by some of his people, and the invaders easily forgot the man used humour as a weapon. Jason Wing’s two metal breastplates Used by and Best before eloquently express the position in which Bungaree found himself.

This is an exhibition of recovered memories, as what was lost, in deliberate acts of amnesia, returns, as the present is reconciled with the past.