It used to be that Biennales self-styled their hype as "the best of the best". Phrases like 'cutting edge' lent the artworks and artists they included a sense of front-line bravery, even after militaristic terms like ‘avant-garde’ had been rejected as part of the hubris of modernism. International survey exhibitions of that kind of scale used to be more rare. These days they’re less so, to the point where it’s not so unusual to find the proponents of the ‘most exciting international art’ working as a postgrad student in some local university, or perhaps on a residency there or somewhere even deeper in the regions.

What once seemed to be a vast gulf between that mysterious value-system that defined ‘international art’ from local product has shrunk like a billabong submitted to global warming. Those with sufficient surplus cash to spend on art-schlepping tell that there are tried and true die-hards that keep popping up as token representatives from one Biennale to the next - names that tag a national association to their bio-data as an ersatz identity while they roam the art-ghettos of the globe.

Even the same works pop up – remodulated, revised, reconstituted, reconstructed – but basically, the same ideas and materials year in year out. But when the onus is on the curatorial thrust as much as the work itself why should there be change? The change can happen as a result of the particular spin each new curator brings to the work, and to the change in context. If there ever is a change in context.

As the inheritor of the claim of being one of the three oldest Biennales in the world, the current Biennale of Sydney’s claim to be “Australia’s largest and most exciting international festival of contemporary art” proves that so much of the tried and true hype still sticks like glue. It could be true. But there are few who would care enough to argue the point. To do so would be as churlish and provincial as Sydney chucking a wobbly about losing the 2014 G20 Summit to Brisbane, as John Birmingham points out in the Brisbane Times: “A true world city wouldn’t bitch and moan about missing out on the G20 summit. A truly bitchin’ world city would shrug and go back to admiring its fabulous self to the exclusion of all others, only breaking off to smirk a little bit at the embarrassing enthusigasm (sic) in the next room, where the upstart hick town is noisily, er, pleasuring itself.”

It would be unduly vulgar for any upstart from that same upstart hick town to critique this year’s Biennale of Sydney as perhaps being not exciting enough. It would be equally truculent to express disappointment at the fact that so many of the works – like the tiny trees meticulously cut from designer paper bags by Japanese artist Yuken Teruya appeared in Australia years ago in the 2004/05 Asia-Pacific Triennial; or that similar small papier maché figures by Kamin Lertchaiprasert had delighted visitors even before that at the 1996 APT; or even that the wonderful ‘cloak robes’ meticulously assembled from the detritus of his African home town by Ghanaian El Anatsui were featured at Okwui Enwezors’ Paris Biennale this year along with Nicholas Hlobo’s fetishistic stitched paintings. That’s just par for the course. And it’s just unfortunate if part of your expectation is to go to such shows expecting to see something ‘new’. It’s probably very ‘last year’.

Which is not to say that the surprises – and the delight that comes along with them – are here and there as well, and sometimes from quite close to home. Gabriella and Silvana Mangano’s video Between near and far appeared oddly familiar and hauntingly strange at the same time – a region of strangeness that might have drawn on landscapes somewhere between the spiny ranges of Sicily and the bald melancholy stillness of Stanthorpe’s rocky outcrops. Which, of course, it did.

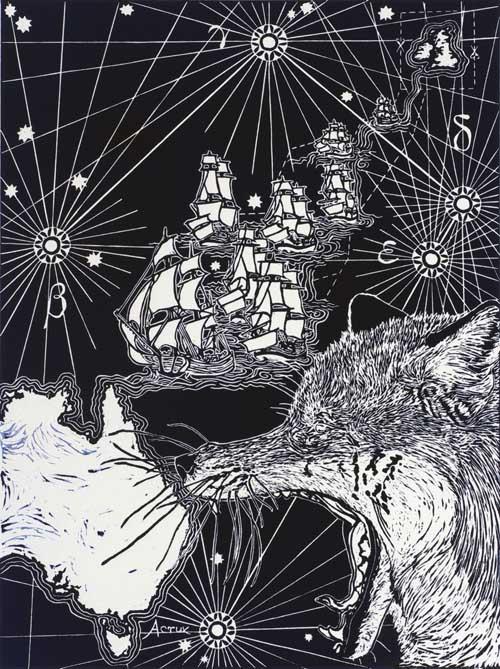

We have come to expect that all Biennales have their signature piece that stands out in the memory as something around which the entire exhibition tends to relate. At times these works can define a moment of history – a point that separates a before-ness from an after-ness. Djon Mundine’s installation of the 200 burial poles worked on by 43 artists from Ramingining at Pier 2/3 for the 1988 Biennale of Sydney: Beneath the Southern Cross, is one such work. Other works stand out because of the sheer scale of investment as much as inventiveness. AES and F’s Feast of Trimalchio at the last Biennale of Sydney will be remembered as such. It’s even what it was about.

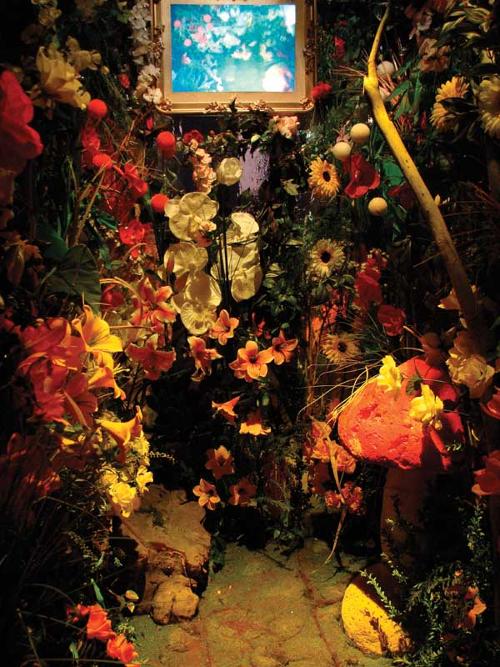

This year’s totem of investment comes in the form of architect-artist Philip Beesley’s (and his team of at least 15 collaborators) Sibyl; a high-tech sense-surround environment that poses questions about the degree to which architecture might evolve a sufficient level of responsiveness to humans, climate, light, interaction, to warrant being classed as ‘alive’. Despite the teams of researchers from a range of disciplines, the work retained its own fragile, floating magic, suspended as a clean, meticulously fussed-over cloud within the dank, stained and dripping chambers of its incarceration at Cockatoo Island. Gee-whiz aside, the work still managed to susurrate poetry, albeit in a spectacular way.

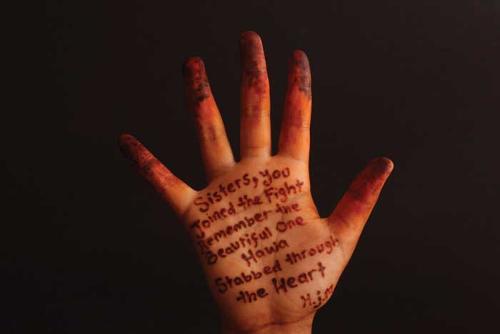

But perhaps, as previously suggested, the works are not what we come to expect to appreciate – or even remember – about such Biennales. If it’s not about the ‘new’ or the most spectacular or the most challenging (and the title and curatorial brief for this exhibition all our relations, is avowedly post-critical), then it’s about the particular spin the curators put on assembling the works. Catherine de Zegher and Gerald McMaster’s frontline dismissal: “We are moving on from a century in which the radical in the arts largely adopted principles of separation, negativity and disruption as strategies of change” was moderated by their advocacy for art that offered “collaboration, conversation and compassion in the face of coercion and destruction”. Enmeshed in that kind of web of connectivity, critical responsiveness seems kind of boorish.

The weather was terrible.