In 1950 Francis Picabia quipped "I always liked amusing myself seriously". Many artistic generations later in 2012, but in a more self-effacing manner, Tricky Walsh said “I am just a big nerd”. She was referring to Science Fictions her latest exhibition. Consisting of balsa wood sculptures/models/maquettes mostly locked into vitrines, and gouaches, Science Fictions is obviously the result of concentrated studio discipline but also the energy derived from recent residency projects in Indonesia and the United States of America. Combining joyously diverse and streetwise popist elements with the meaty weight of traditional sciences and architecture Walsh suggests a more positive, still speculative world than the dystopia that our politicians and media constantly reiterate. Encountering the works in this exhibition, I am sure that Walsh would be excited by the idea that scientists have created a completely artificial cell, one whose sole parent is the computer. (See Dr. J. Craig Venter, New York Times May 20, 2010). Indeed in these works we are introduced to piezoelectricity (discovered in 1880 by the Curie brothers, used now in reverse form but one of the many great hopes of alternate energy afficionados).

Science Fictions reminds the viewer that behind the ideals of mathematical perfection and schematic abstract forms that infuse the everyday there lurk the shadows of visionary artists, scientists and philosophers. What can be more mystical, more mysterious and epic than the leitmotifs of the modern - pure energy and light? However Walsh is not a slavish cosmologist, rather she engages in critique of present day practices and attitudes. Her position seems similar to those retro-active stylists of cinema Terry Gilliam (see Brazil 1985) or Jean Pierre Jeunet and Marc Caro (pre the ghastly Amélie 2001). There are other echoes in Walsh's work such as the quirky inventiveness of Belgian artist Panamarenko and the intricate miniature worlds of the later Chris Burden and Paul Etienne Lincoln.

Science Fictions is “meccano-morphic”, a handy word devised by Francis Picabia to describe a symbolic vocabulary of machines. A cycle of seven brightly coloured gouaches are the key to the exhibition. Stylised radiating and oscillating flows of energy, they are part decorative and objective chromatic exercises and part quasi-mystical diagrams like the occult pathways to knowledge found in the Kabbalah et al. This series of works could also operate as a set of symbolic portraits of the artist’s friends or suggestions of various psychological states of mind. The most intriguing of the cycle is Water drop static electricity generator. It depicts a Duchampian impossible (i.e non-functioning and therefore tragic) machine emerging from a vortex of coloured shards.

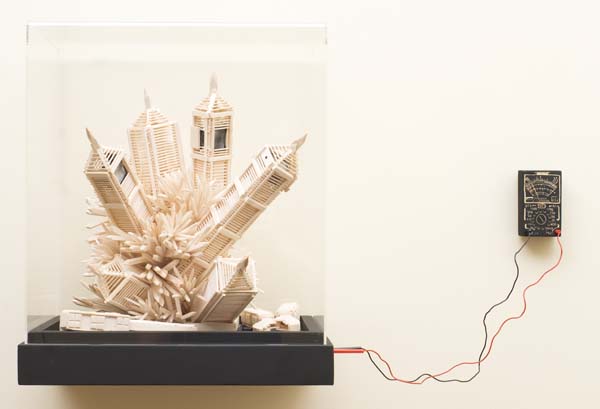

Crystals of all sizes, colours and forms inhabit this show. Of late their fascinating beauty, even magic, has been somewhat compromised by New Agers obsessions. But again Walsh confounds expectations with works like Light emitting geode where an obviously fake polished stone reveals a crowded cityscape at its core. The quartz crystal piezolectric generator is a fractal explosion of original natural mathematical structures that morph into a bevy of skyscrapers, more kitschy 1980s historicism than the Art Deco gems of New York and Chicago. Significantly this complex form is further activated by a gauge measuring perhaps further growth. At first glance objects with a scientific purpose, all of the models have a strange imminent anthropomorphic quality. A grid of 9 explanatory drawing decals help the viewer to decode the exhibition. But these works also confuse – almost working drawings they are too mediated, too finished to operate as documents and look back to the artist’s long engagement with cartooning and zine culture.

Walsh asks audiences to embrace the unexpected. In the delicate gouache Watermelon Tourmaline candelabra and clamp (the piezoelectric series), one of a series of 4, the natural form of the crystal is destabilised, almost violated by clamps. Here the juxtaposition of the human-made and compelling marvellous nature creates an entirely new creature.

This exhibition reveals a sophisticated development in Tricky Walsh’s oeuvre.

It is a journey of intricate detail, voyeuristic witnessing, wry subversive reversal and selective disjunction of form, purpose and content. Science Fictions underlines a new confidence, a consolidation and refinement of style that heralds an artist of note.