This exhibition inadvertently comes as something of an antidote to two major exhibitions that have recently circulated in Australia, both of which championed the classical Modernist history of Twentieth Century art. The Beyeler and the Paley Collections were both extremely popular with gallery goers, perhaps drawn by the prospect of having a moment's commune with a masterpiece that may have been familiar to them through reproduction on anything from a postcard to a coffee mug. The sting has largely now gone from these once highly oppositional works, there were few surprises and fewer mysteries. There were also no works by women in these shows.

So what were women artists doing this century? Inside the Visible does not claim to be an alternative exhaustive chronological survey that will lay all before us, rather 'an elliptical traverse of 20th century art in, of, and from the feminine.' [1] As such it is quite a personal view of the Curator, Catherine de Zegher, Director of the Kanaal Art Foundation, Kortrijk Belgium. She developed the exhibition from a series of twelve process-orientated solo shows held at the Beguinage of Kortrijk, a medieval secular convent, resonant with a history of housing semi-religious congregations of women. Perth is the final venue of the tour which began at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston and followed at the Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington and then the Whitechapel, London.

The discourse of locating the margins and bringing them to the fore is now a familiar one - the cynics amongst us have said 'The art market needs the marginal to feed its appetite for novelty; the manufacture of marginally is its business' [2] and while there is a truth to that, the real need remains to uncover the work of hidden artists and, as this exhibition tries to establish, tease out correspondences between artists working across different generations and nationalities. The 33 artists in the show come from three significant periods of history: the 1930-40s, the 1960-70s, and the 1990s. Each period witnessed the rise of repressive systems, racism and conservatism - ripe conditions for marginality. Rather than being hung chronologically however, they are grouped in four loose sections; Parts of/for - The Blank in the Page, The Weaving of Water and Words and Enjambment: " la donna è mobile". The curators have deliberately avoided grouping the individual sections too tightly and whilst this approach is attractive on paper, the resulting installation in the rather unforgiving brutalist interior in Perth seems confusing. Some connections do however stand out, such as the opening view of Claude Cahun's constructed self portraits from the 1930s and Nadine Tasseel's contemporary photographic tableaux vivants, where the artist presents herself behind a series of masks that themselves are reproductions of ideal beauty from well known historical paintings. Of the two one feels more passion in Cahun's small prints - as a woman, lesbian, Jew and member of the Resistance, she lived the ambiguities of gender that she so enigmatically created with her photographs.

As artists in the margins, the women in this exhibition made at times direct responses to the political and social climate of their day - most notably Martha Rosler's Bringing the War Home 1967-72 where montage is used to bring the Vietnamese tragedy into the affluent American domestic space. Rosler's intentionally confrontational series is at odds however with the sensibility of most of the rest of the works in the exhibition where one finds a distinctly female aesthetic hand at work - works which echo conventional notions of the feminine - they are detailed, fragile, intimate, ephemeral, luscious; where are the bad girls and their loud, ugly, hard, brash art? - Cindy Sherman, Jenny Holzer, Cady Noland or the creepy - Annette Messanger or Sophie Calle.

Unfortunately the Australian venue is so in the margins that some works have not made it to the showing here - Hannah Hoch, Agnes Martin and Susan Hiller are significant in their absence and other works have been changed. The Cecilia Vicuña installation is a pale echo of what was seen in London, and the site-specific installations of Ann Veronica Janssens and Joelle Tuerlinex, both contemporary Belgian artists whose work was seen in the original Beguinage showings, have not travelled well. Janseen's sound installation in the stairwell and Tuerlinex's 'insertions' with a floor level slide projector sending out pinpoints of light, seem like footnotes rather than real participants in the exhibition. Sadly the more resonant installation by Mona Hatoum also suffers in its new context.

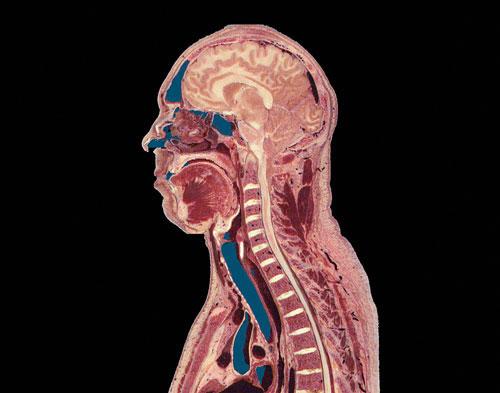

Hatoum grew up in Beirut but was forced to leave in 1975 with the coming of war. She has since lived and worked in the UK, but her art remains informed by her sense of displacement and memories of violence and lost intimacy of the family. Her works are often genuinely physically confronting for the viewer and she has previously made performance/video work using her body "... as a site of metaphor or allegory for social constraints and the act of freeing oneself" [3] Although the artist is herself absent from Recollection, parts of her remain in the hair balls made from her own long dark hair. They drift along on the movement of air like tiny tumbleweeds in the desert. The viewer is drawn to a small table onto which a loom has been clamped and finds a loose grid of hair in the process of being woven. To reach it one must pass through an almost invisible web of hair hanging from the ceiling. There is no escape from the artist's presence. Woman's hair, particularly in Hatoum's Arab culture is a potent sexually charged symbol, usually kept hidden by the veil. This installation was initially conceived for the Beguinage within whose dark spaces echo the patient work of generations of women who in order to be liberated from conventional female roles chose to be confined. Slides that de Zegher showed at a talk on this piece show this context to be far more appropriate than the stark whiteness of the gallery and perhaps another of Hatoum's works could have been chosen for this new context. Despite these concerns however the exhibition remains an important one and it heralds a shift at the AGWA towards the programming of more weighty exhibitions dealing with contemporary critical issues.