This is an important exhibition - the first time in recent years that the main art institution in China (the National Art Museum of China, NAMOC to those more used to it) has sent an exhibition of Chinese art to Australia, and NAMOC like everyone else in China is very aware of the power of their country internationally. So when they send a show of their work, very proudly as the catalogue makes clear, to another country and just to one venue, we should pay attention. (It should be noted NAMOC has just sent an exhibition to the National Museum of Australia in Canberra. A New Horizon is divided into three sections and samples Chinese art from 1949 to 2009. It is on from 30 September – 29 January 2012.)

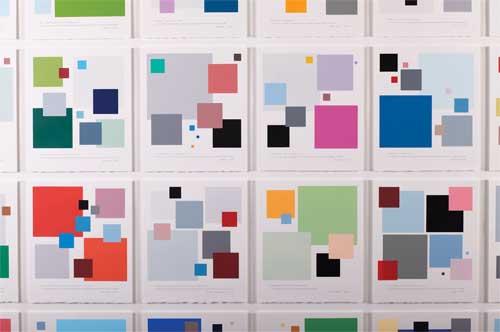

For a Western audience Reflections of the Soul is a strangely difficult show: large brush paintings on paper by nine senior members of the art establishment in China. It isn't Ai Wei Wei, or Maoist Pop, or the Song Dong et al work well-known and admired and accepted in the West as part of global discourse. As Robert Nelson, art critic for The Age wrote (3 August 2011), brush painting can seem "outmoded".

That word "outmoded" is telling. The Chinese are there for the long haul. They invented paper and ink, and they were making art like this long before there was an idea of what was à la mode, or not. They see it as intrinsic to their cultural history and offer it to us as a unique experience. As Caroline Turner recently reminded me, this understanding informs the work of globally-admired artists like Xu Bing and Cai Guo Qiang.

I was conscious of the physicality of this show – the size of the works, the richness of the ink, the softness of the paper, and being surrounded – enfolded – by it. I was aware that the Chinese admire art’s ability to invite us to enter a realm of contemplation, a physical reverie, to view 'higher’ things, to lose our sense of the mean and material world. I was aware of the flatness of the work, the lack of illusion or ‘reality’, and that it was up to us as viewers to make the effort to step into it and let it take control over us. We have to take that step into other shoes so crucial to seeing works from another culture. White Australia is conscious of the journey to understand the different qualities of Aboriginal art from those of Western perspective and material realism, and to feel the liberation of this understanding. We need to apply this experience to others more easily than we do.

I remembered the telling story of the fish in the aquarium described by both Japanese and American businessmen. The Americans described the big fish; the Japanese first described the water in the tank as the environment for the fish. The East Asian cultural way of seeing the world is to see the whole with individuals within it, feeling the spaces between each object being as important as the object. They understand individual artworks and artists within a total whole (and when they step away from this, as does Ai Wei Wei, they are very aware of what they are doing – though he too of course as in his Tate Gallery sunflower work includes this issue as central to his oeuvre). It is a very different – and intriguing – way of arranging how we function as people in society. Robert Nelson might see this as lacking in “liberality” or individuality. Indeed it might be, but we need to understand it and measure it for its worth.

One of the important offerings of this exhibition is that, mostly, we do see much more ancient brush paintings from China, often centuries old, in touring exhibitions and collections in Australia, with the ink faded (as it does), the paper discoloured (as it does), and protected behind often very heavy and off-putting glass vitrines, but here you get close and ‘feel’ the texture of the work – let it drift over you.

For all the positives of the show, there remains, for me, an issue the Chinese do not seem to have addressed – which is to think themselves of how a different audience might react.

There is a sweetness in some of the works that Western critical audiences dislike. We are too cynical perhaps. A cross-cultural exhibition organiser has the delicate task of sending into another cultural space first what they want to show, but also needs awareness of what the audience wants – or is willing – to see, and of how much knowledge they bring with them. Negotiating that is the challenge for everyone.