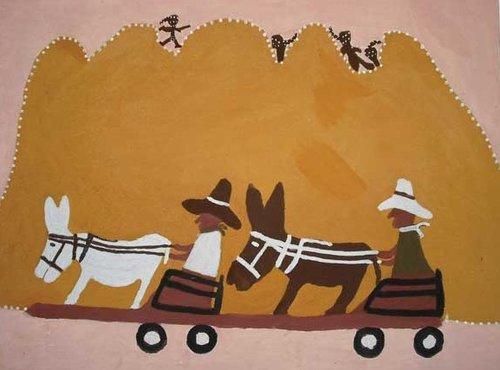

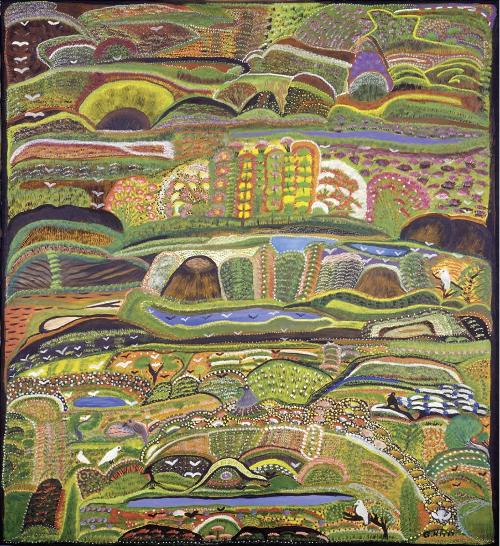

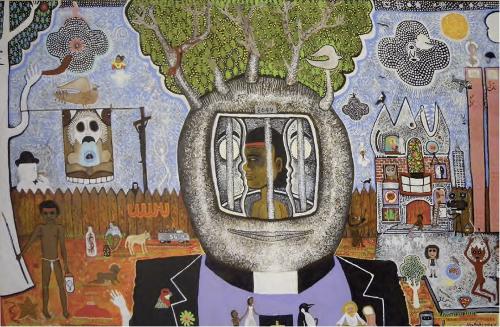

Zoe Porter's latest performance installation sees her previous drawings and paintings extended to realise a grander, more interdisciplinary environment. Featuring painting, music, video, acrobatics and pre-recorded soundscapes, Porter draws together several concerns regarding the relationship between the human and the animal in order to engage with a site-specificity which is simultaneously surreal yet uniquely Australian. The extension of her works on paper into both the third dimension and public space have allowed her to articulate a more elaborate vision of her investigations into the relationship between art, nature and the politics of place. She achieves this through references to the Australian bush, scattered throughout the painted and collaged figurations of the installation which introduce the viewer to her anthropomorphic transformation during the accompanying thirty minute performance.

Donning a costume evoking a marsupial-like creature, Porter plays handmade instruments, paints directly onto the gallery walls and interacts with her two similarly costumed, nameless accomplices in order to utilise all parts of the installation as a kind of landscape. The remains of the impact these characters make upon the gallery - instruments, amplifiers, paints and sheet music, form the basis of the installation for the duration of the exhibition. The accompanying video footage projected onto the wall adjacent to the performance feature the shadows thrown by a man dancing in a public park, elusive and mutable.

The open-endedness of the relationships established between the viewer, Porter and her anthropomorphic conspirators during the performance-event opens up new possibilities for imagining place and our impact within it. She poses these possibilities through the potential for audience participation via acts of creativity in public space, of which the man featured in her projection is an example. Her decision to leave the debris of the performance within the gallery space leaves open the potential for further ongoing collaboration through the audience’s involvement with the work in progress.

The surreal anthropomorphic beings featured both in the performance and painted aspects of Porter’s installation sit on the crossroads of her artistic concerns. Not quite human yet not animal, they often appear to be in shamanic states that are familiar to the viewer due to their usage of Australian iconography while simultaneously alien due to their discordant, semi-conscious nature. In the performance of Conjure, these beings struggle to articulate a world in which the role of the artist functions as a conduit, transporting the audience into surreal situations evoking the Australian landscape.

Porter’s past works found audiences at music festivals, cultural exchanges and street corners, sites that better suited her refusal to allow completion or closure in preference to considering her practice as an ongoing exploration. In this new work the 'relics’ she has consciously left behind from these endeavors - painting debris, stencils, stickers - trail back to the gallery. Her inclusion of sheet music, instruments, dance, light and smoke machines into the performance also demonstrates her unwillingness to categorise her practice into a tidy genre.

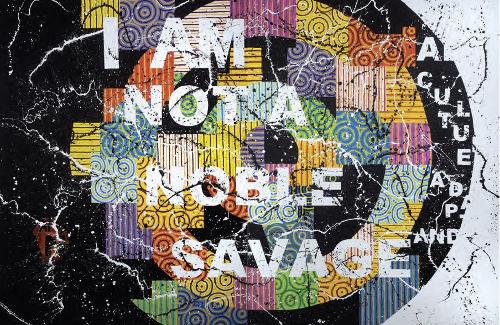

The staging of the work in the large front space of Level Gallery suggests an imagining of place which could be easily contextualised as a new genre of three dimensional landscape painting. This constructed landscape evokes Australian flora and fauna in a way which extends beyond simple interpretations of national identity towards a more complex and ambitious consciousness of place. The dualities of private and public, flatness and dimensionality, dreams and reality allow Porter and her collaborators to create interpretations which go well beyond any tired artefacts that might shape the dominant imagery of more standardised interpretations of ‘Australia’.

Thus we can see a post-colonial tendency at work in Conjure which disavows the notion of a grand narrative of nation in favour of a more flexible, ambitious reconstruction. By engaging with post-colonial theory by way of the surreal, Porter’s interdisciplinary landscape considers notions of territory, both animal and human, to suggest the parameters of a kind of dream-world where the artist functions as a central visionary representing both nature and culture. The three collaborators who appear to be caught in a state of becoming between being drawings, animals or humans, make music, painting and gestures that offer a loosely choreographed means of interacting in this half-dream, half-real scenario. They invite us to do the same.