An exploration of the self-portrait drawn entirely from the National Gallery of Victoria's own collection, "The Naked Face: Self-Portraits" presents a broad selection of 150 works from the last 500 years of art. The exhibition is guest-curated by Dr Vivian Gaston, and her ambitious attempt to draw together and coherently install such a broad range of work has received some particularly critical reviews (I refer here primarily to Christopher Allen’s article 'Face Facts’ published in “The Australian”). I hope to offer a more tempered response, but there were a number of issues with the exhibition - primarily with the exhibition design – that I found difficult to put out of my mind when walking through the show, and now in reflecting upon it.

Previous surveys of self-portraiture have narrowed their focus to a particular medium or historical period, such as London’s National Portrait Gallery’s “SELF-PORTRAIT: Renaissance to Contemporary” (2005) which surveyed the Western painting tradition. “The Naked Face” is not so restricted. From the moment of entering the first gallery this is immediately made clear: a Chuck Close extreme close-up self-portrait faces you, while an ornate 19th century mirror leans against an adjacent wall. On an opposite wall sits an 18th century book on physiognomy open to a spread of drawings of eyes, and some other small works. The intention was perhaps to warm the audience up for what is to come: provocative connections between works usually separated by region, period, and medium. It achieves this, but unfortunately also foreshadows the exhibition’s weaknesses: confusing, often awkward, installation, with little breathing space for the work or the viewer.

The works are divided into thematic sub-groups such as ‘the Artist’s studio’ and ‘the Artist’s Body’ and ‘Empathy: Self and Others,’ which lead to some interesting juxtapositions between contemporary and historical works. However, the way the work was presented continued to demand attention above the works themselves. For example, the heavy-handed decision to have mirrored walls in the section dedicated to ‘Narcissism’ compromised the viewer’s ability to look clearly at the artworks. Furthermore, whatever the conceptual links to be drawn under the rubric of ‘Performance’ between Andy Warhol’s “Self-portrait no. 9” (1986), a Coco Chanel suit, and a Zandra Rhodes dress, their close grouping appeared to have been put together by a retail merchandiser.

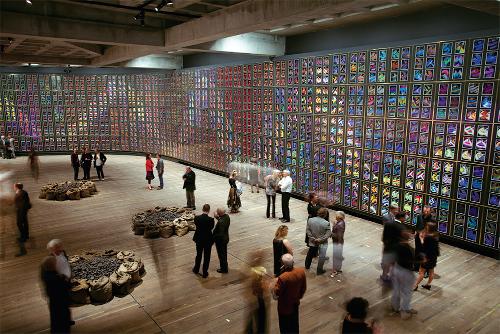

Another issue was the crowding of work. The sheer number of artist’s self-portraits placed together on the same wall reduced them to a crowd of confused faces. The best moments in the exhibition were found when a work was given (or demanded) its own space. For example, Vernon Ah Kee’s large-scale “Self-portrait (possesses some of the attributes of an artist)” (2007) looked open and strong, whereas smaller works – even by great masters – were entirely lost as a consequence of the installation.

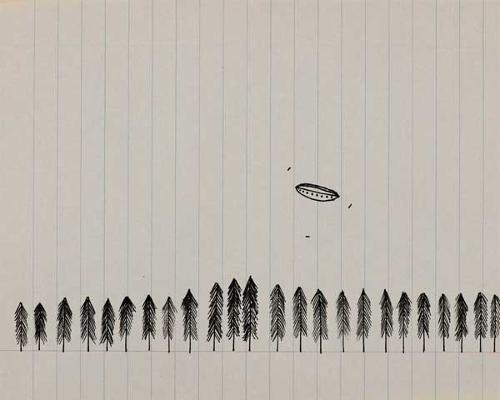

Nevertheless, the curatorial decision to divide the works by theme as opposed to ordering the works by period or region had positive consequences. Firstly, by forming new taxonomies for the genre, Gaston was able to convey some of the subtle developments in the genre over time, such as the reformed attitude to the artist’s body and the development of the avatar-self (such as Kate Benyon’s “Li Ji: Warrior girl” (2000)), as opposed to the 18th century focus on realism and self-scrutiny. This success, no doubt, reflected her considerable academic research into the area, and into the collection she drew from. Finally, the original conceptual links that were drawn in the first gallery introduced an element of risk to what could otherwise have been a safe exhibition. It was unfortunate that these links were not continuously better articulated through the placement of the works.