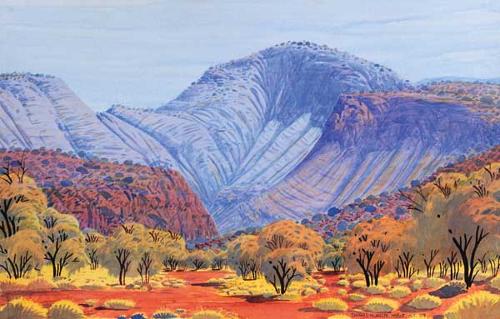

It's a strip of landscape - a sliver of endless gibber plain. The photograph is sliced into equal flat planes of land and sky. The surface of the earth is as old and scabrous as time itself. Only stunted bushes and intermittent shocks of dry grasses have bothered their way through the scabrous eczema of the desert’s surface. A levelled, ancient, un-giving land. And yet, above it, the clouds stretch back into forever, and the last rays of the day’s end paint the entire scene with a sublime endlessness as unfathomable and silent as it is unremarkable.

Across this landscape, beneath this sky, an alien figure stands alone. The title of the work, "Pope Alice (Lake Galilee)", is as redolent and as evasive of easy meaning as the landscape itself; the title suggests Biblical places and holy personages, and yet the time and the place and the central character are from a holy story of another dimension.

Here the Pope – aka artist Luke Roberts – has metamorphosed into a strangely alien creature – an apparition drenched in a whiteness that could be purity or emptiness or holiness or, perhaps, just another nutter in drag; someone who’s got together an upside down lampshade, rubber wash-up gloves and a gimp mask to wear as he staggers through the desert.

Strange, perhaps. But perhaps not out of order in the canon of historical figures and tales Australia claims as its white history.

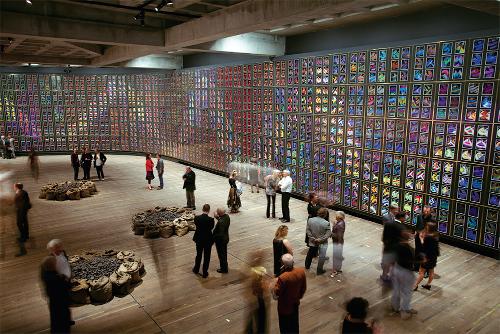

Sometimes, in the gallery silence of the very best kind of survey shows, you can hear pennies dropping one by one. The exhibition titled “AlphaStation/Alphaville”, a joint project between the ACP and the IMA focussing on the photographic work of Luke Roberts, uses early images from the artist’s childhood to begin a wild, rollicking, take-no-prisoners journey that both begins and leads back to Alpha – the tiny Queensland town where the artist was born. In these first images we see the artist as a child posing for his sister as a pharaoh and as a vampire. Behind him are the tell-tale clues of the Ozzie backyard – the weatherboards of the house, the home-made swings, the galvanised iron of the water tank – features that do nothing to diminish the absorbed gaze of the child who looks back at the camera like a lover.

In a later suite of works, titled “Where’s the Circus” (1973 - 79), the artist’s personas have expanded into a pantheon of characters - the geisha, the vamp, the exotic other from the Middle East, a soldier from the SS, and between these collections, larger than life, the image of “Alice Jitterbug (Birth of Venus)” (1977) gracefully hosts the celebration of a lifetime of camping and vamping that has performed for the camera on the borderlines between genders, creeds, fears, faiths and folly – all those tender spots where Australian anxieties have historically manifested themselves as being most acute.

However in this exhibition the artist’s more recent work turns back on these images like an erebus. In these works the artist’s return to Alpha – to the ground-zero from which all these hauntings emerged – throws (celestial) light on the depth and seriousness of so many works that could be read as joyously and ribaldly inconsequential. In “Asencion (Strange Fruit)” (2010) the legs of a man wearing black high heeled pumps are the only figurative clues we are given, hovering beneath a tree in an inner-country landscape that is recognisably dry and impassive. The legs are suspended, exiting towards the top of the image, so that it is unclear whether we have just missed witnessing either a hanging or a miracle.

The taut lines between laughter and sobbing stretch through and across so many of these works: in the left panel of the diptych “The Spearing” (2009) a profiled cowboy posed in the landscape against the strands of a barbed wire fence seems caught in motion as he arches backwards, throat thrown to the sky. In his hands he holds a copy of a book titled “Tyrants – History’s 100 Most Evil Despots and Dictators”. In the right hand panel an Aboriginal figure – an elegantly attired Richard Bell – is posed with what looks like a spear in a white studio shot. The reverberations between the two images ricochet between histories that are both past and present, personal and public.

This is a show that is as much about a country’s obsessions and fears and phobias as it is about this artist’s rich personal imaginings. And about the Alpha that as Australians we all belong to.