It is a truth universally acknowledged that Festivals and Biennales are now more about the creative vision of particular curators than the presentation of new works of art.

The 'Berlin Biennale' has more at stake than most. The visual riches of this city make New York look like a poor cousin. Above all, many of the political traumas of the 20th century were centred on or around Berlin. As the new city has risen from the rubble of its past, it has used the visual language of innovative design to trumpet its message of transparency, equity and penitence. No art exhibition can compete with such a context; instead it must work with it.

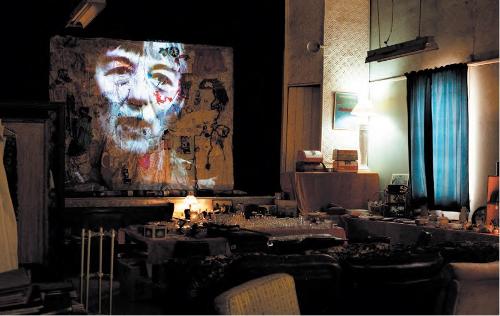

Katrin Rhomberg's thesis is both about the nature of reality, and the consequences of living in a world where we do not know what can be true. As a part of that reality she has taken the changing shape of the city and incorporated it into the art. So the exhibition begins in a derelict warehouse in Kreuzberg, where three floors of installations, films and other works compete with the derelict space. The best of the films (for example Phil Collins’ 'marxism today (prologue)' deserve a proper screening space) but as the installation doesn’t do sound barriers, no work can be looked at on its own terms. However Adrian Lohmüller’s installation 'Das Haus bleibt still (the house stays calm)' manages an intelligent intervention throughout the entire four floors of the building complete with seeping water, gas pipes and condensing salt.

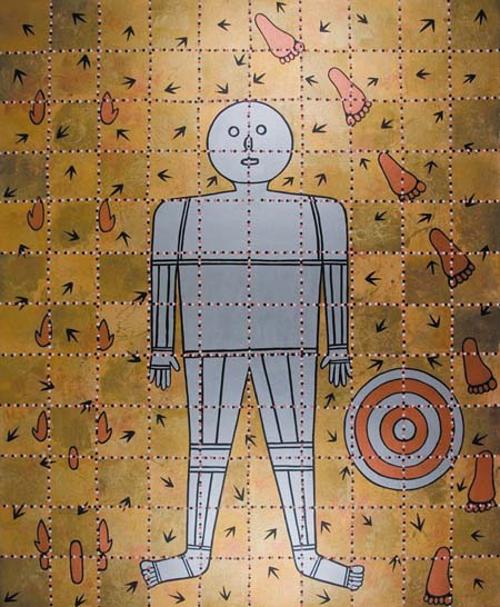

Until recently Kreuzberg was the home of the poorest of immigrants and guest workers. Now, thanks to the intervention of artists and other admirers of its elemental grunge, it has begun a rapid climb to fashionable edginess. Its reality is already in transience. The second main venue is at the KW Institute for Contemporary Art in Mitte, in what was the old East. Modern renovations have already turned this part of town into something like Newtown on ice (with fewer trees and more bicycles). This upmarket venue (with the most overpriced drinks in Berlin) is where Mark Boulos’ searing installation 'All that is Solid Melts into Air' places the angry bearpit of the Chicago Mercantile Exchange in opposition to the ritualised responses of residents of the Niger Delta whose lives have been destroyed by Big Oil. The presentation gives this work the kind of respect it needs, and it is a pity some of the Kreuzberg installations were not so well treated. The work that is most valorised at KW is by the youngest artist, Kosovo’s Petrit Halilaj. He has been given the space to build a revised version of his family’s former home. The structural timbers go literally through the roof, and a flock of laying hens give the impression of rustic authenticity. It is not a solid structure, more a skeleton, with the same openness as Albrecht Altdorfer’s paintings of nativity scenes. The curatorial hand lies very heavy here as on the second floor visitors are directed to a large white room (so blindingly totally white that it was assumed be an artwork in its own right) where the only content is the view, through a window, of Halilaj’s house growing through the roof. I can understand why Europeans, especially those from cultures that still bear the scars of World War II’s genocides, are especially sensitive to a young artist from Kosovo, but does this work really deserved its privileged treatment? Is the artist at the age of 23 old enough to understand that he is simply an element in Rhomberg’s composition?

The third component of the 'Biennale' is Germany’s heroic past in the form of a retrospective of the work of 19th century artist Adolph Menzel. This is at the Alte Nationalgalerie, an institution not usually frequented by the art-loving avant-garde. Menzel was the ultimate realist. His precise drawings of the dead prefigure the work of Otto Dix. But he was also a mythmaker, and used his access to the deathmask of the 18th century monarch, Frederick the Great, to make that friend of Voltaire truly greater than any reality. This third focal point makes the 'Berlin Biennale' especially successful as it turns the exhibition as a whole into a statement on the variety of this city in flux. It also reminds the viewers that all constructs - even the most rigorously observed realities – are shaped by value systems and circumstance.