The speed of change in politics, climate and the economy is driving a need for major shifts to human activity. New ways of collaborating and cooperating need to happen if the self-destructive gene is to be sidelined and new paradigms be found. The world is not short of thinkers who have been working along these lines for some decades, and many artists can count themselves amongst this group. One of the manifestations of the public interest is the way cities are built and rebuilt, and art which manifests in the public arena is part of this nexus. But the idea of public-ness has moved too far in the direction of control by private and profitable interests. Commonly in many cities around the post-industrial world old docklands have been appropriated by developers and changed from a democratic organism of work mixed with recreation, albeit mostly whoring and drinking, to polished palaces of shops and flats where exuberant, eccentric or riotous behaviour is only tolerated if football is involved.

As in Melbourne's Docklands, these vistas of marina, restaurant and shopping mall punctuated with glittering tower block apartments are soon dotted with 'public art’ in an attempt to create visual distraction from a woeful lack of planning for livability.

Since the turn of the century the realisation that we must turn this around and reclaim the public space has dawned. How to create systems of controlling human behaviour not imposed by the profit imperative but agreed for the public good is now being pondered at various levels of governance.

Media that offer looser definitions of art and entertainment have arisen. A festival is an ancient behaviour of human beings, a periodic ritual in which people take part, some as actors, some as audience, some as both. Many very old festivals have survived to this day. Some have gone to be replaced by new ones, or to be revived in a new form. The Crab Festival of Egremont in the Lake District of England emerged in the 13th century and celebrated the harvest of crab apples. The annual contest was to climb a greasy pole in order to claim a prize on the top and this survived until 2003 when the town council found they could not get public liability insurance. It took the artists of neighbouring Grizedale Arts to remake the pole in carbon fibre and restart the ritual six years later.

Festivals using ancient models like these have the ability to temporarily alter familiar surroundings, and renew our vision of our patch without remaking it. But in settler societies like Australia the festivals of the motherland tend to disappear after a couple of generations as their relevance diminishes. Who knows, it if wasn’t for the retail industry Christmas itself might die out. Other festivals have taken their place - starting with ethnic festivals like Carnivale and Glendi, followed by an ever-growing series of multicultural, food and wine, comedy, fashion, film, writing, music, surf festivals and the more recent appearance of smaller environment and place-based celebrations such as the Leafy Sea Dragon Festival of Yankalilla in South Australia.

Novel art forms which arose thirty years ago took some aspects of festivals to a different level. When Christo wrapped Little Bay in Sydney he altered that rocky shoreline without harming or changing it in any way.[1] Krystof Wodizco pioneered huge word and image projections on powerful buildings of state and industry which, without exposing himself to prosecution, helped to create virtual but lasting scepticism in our regard for these institutions.

In 2010, and in more celestial mood, Rafael Lozano-Hemmer’s 'Solar Equation' at Federation Square in Melbourne, brought a huge sun to the winter nights of July. Upon this gigantic orange star a continuous play of solar flares and roiling disturbances were ‘designed’ by ordinary people whether in the chilly street below with a special i-phone application or online from anywhere in the world. The Light in Winter celebration, conceived by doyenne of festivals Robyn Archer, harks back to ancient Northern Hemisphere midwinter celebrations, including the Romans’ winter solstice of 25 December – a way to exorcise the dreariness of darkness and cold with a mixture of bonfires, alcohol, dance, evergreens, feasting and mystery pageants. Archer’s signature programming aims to bring people of all ages and interests into contact with inspired artists such as Lozano-Hemmer whose inventions can offer experiences that are personally rewarding, in this case a high octane brush with the city at night. As a foil to the spectacular of the big sun she invited Indigenous groups to maintain a live fire on the square and musicians to capture unsuspecting passers-by into joining singalongs.

To the serious international world of public art commissioning, with its squads of committees, city authorities, power brokers and large investments, these innocent pastimes might seem irrelevant.

There are literally some big things at stake this year in London where Mayor Boris Johnson, in a climate of austerity, claims to have secured the $34m budget for the proposed 120 metre high twisting steel tower titled 'ArcelorMittal' Orbit at Olympic Park after he bumped into steel baron Lakshmi Mittal in a Davos cloakrooom. Anish Kapoor, with Cecil Balmond won the limited design competition for what will be the largest artistic commission in the world; in its scale and material Kapoor acknowledges it as a relative of the Eiffel Tower but Orbit’s marvellously lurching loopy design seems more like Tatlin’s Tower meets the Tower of Babel and faulty British engineering. Is it something about the Monty Python silliness of large English artworks complete with upperclass twit pronouncements by the Mayor of London that has fed the British public’s new love affair with public art?

After the announcement of 'Orbit', another forthcoming large landmark sculpture in a corner of Kent between the Eurostar line and the A2, won by Mark Wallinger with a 50 metre high white horse, seems like a bargain at a mere $3.5m. 'Horse', funded by the Eurostar and other rail and road companies, has been an uncontroversial choice, with its nod to traditional chalk horses and local horse breeding combined with a toy-farmhouse-set simplicity. This relaxed and comfortable attitude is in sharp contrast to the hostile reception for Anthony Gormley’s 1998 gigantic steel 'Angel of the North' in Gateshead, near Newcastle-on-Tyne, now, impossibly, to be dwarfed by a horse. If the artist wasn’t a Turner Prize winner we might have asked him whether our Big Prawn or Koala was his inspiration.

With its long tradition of respect for artists and their work, there was never going to be a problem in Germany when plans were unveiled for a whole region in the west to use the arts and culture as a way of reclaiming some heavily degraded land. Formerly exploited by the massive industrial coal mining complex of the Ruhr Valley, the Emscher River was for a century or more used as a concrete-walled open sewer. In their successful bid for the 2010 European Capital of Culture the Ruhr Valley hopefuls decided that the region between the rivers and canals and around several towns would be declared the ‘Ruhr Metropolis’. The program has included a Biennale of Light in May and a huge array of public artworks and events. On 18 July around two million people took part in a day to celebrate the banishing of cars and trucks when an entire 60-kilometre stretch of the autobahn between Duisburg and Dortmund was closed. One side was for bikes and skaters, the other for 20,000 tables where people feasted and witnessed hundreds of performances. Today the Emscher River is still a sewer but art is being used as a reason to reinstate and recreate the natural river. Emscher Art 2010 sees 40 artists creating 20 major public art works in and around the adjoining Rhine-Herne Canal, its sluice gates and surrounds. Now known as a Culture Canal the website advises visitors that they can reach the works and the local art museums and places of rest and refreshment by boat, bicycle and car.[2]

The nexus between tourism and spending on major artworks in the public realm prompts the cynics amongst us to conclude that this unusual interest in contemporary art on the part of the mayors and corporations has arisen as part of strategy to create profits for airlines and hotels. Whereas in places like the Ruhr admission to the sites and museums is usually free, the spending of these new Grand Tourists on their meals and hotels should make up for it. Compared to the normal run of sightseers the disposable income of cultural tourists makes them a valuable commodity to any city or region. The speed at which areas can be ‘regenerated’ by moving in the art squad can be astonishing. Gateshead was the basket case of the north of England before Gormley’s 'Angel of the North' spread its steely wings. Newcastle upon Tyne now boasts the Baltic Centre and is firmly on the art map.

The slower lane

There is another pervasive art practice at work amongst us, often well below the radar, and not part of any grand tour. It is seeded in the universities and art schools, and cross-fertilised with urban planning, sociology and usually funded by the state. Art which redresses the failures of social planning has been developing since the mid nineties, especially in Europe. Key examples of these durational art projects (also known as ‘long-termism’) were expounded in a recent forum in Bristol [3] by an exceptional group of pioneer arts workers who have been working intensively with communities in the Netherlands, Denmark and the UK to tease out ways in which creativity and collaboration can be introduced into places where art is not a household word and no one has been to art college.

Jeanne van Heeswijk is an artist whose practice moved into collaborative and interactive areas around 15 years ago. In 2005 coincident with the development of a new city created on a man-made series of islands in IJ Lake 20 minutes from the centre of chronically over-crowded city centre Amsterdam, she was invited to make a work with and for the emergent community of residents. IJburg was conceived as a city of several hundred thousand, with a mix of renters and home owners. It was clear even as construction was proceeding that socially it would be a rocky road for this ethnically and economically diverse group. Sited between the rented and the privately owned housing was an impressive intriguing villa designed by Koolhaas architects, painted bright cobalt blue. With a price tag of 60,000 Euros this was a piece of pricey real estate. To van Heeswijk it represented an opportunity to take the temperature of the nascent society, to test the cohesion, to perhaps add the spoonful of yeast which would prove the dough. With the determination bred from many previous encounters with public space, local authorities, sponsors, landlords, developers and vulnerable populations, she persuaded and negotiated her way to being given the use of the house, courtesy of a benevolent developer who finally bought it for the project for a minimum period of four years.

Thus began The Blue House, a series of exchanges and encounters that involved bringing in around 55 artists in residence who proceeded to set up an extraordinary range of innovations including a Chill Room for restive teenagers, many from immigrant populations, a radio station with locally produced content, broadcasting from the Blue House every Friday night, cinema screenings on a big screen attached to the house about community housing projects, a ‘car hotel’, a flower stall and many more. [4]

The hallmarks of Van Heeskwijk’s Blue House are open-endedness, a lack of programming, an aim to create dialogue, to foster a self-organising non-hierarchical community and to maximise every opportunity for collective action – ‘ a call for sociality’.[5] Remarkably, in order to assert its independence from the city authorities, she neither sought nor received money from them, and the artists accepted minimal payments sought elsewhere. Inevitably, notwithstanding all her altruistic efforts, over the long life of the Blue House there were times when the community turned on her, and became her opponents rather than her supporters. Unlike the relatively straightforward process of winning and executing a physical sculpture, this is public art which demands the life and soul of the producer.

Another long-term project in the Netherlands titled 'Beyond' has come to a close after around seven years. Tom Van Gestel, a director of the non-profit public art agency SKOR (National Foundation for Art and Public Space) in Amsterdam was part of a team of professionals including city authorities, artists, writers and funders who set out in 2003 without a specified aim or an outcome, to connect creatively with people from Liedsche Rijn, a raw new village of 40,000 people on the outskirts of the historic city of Utrecht.[6] SKOR’s role was to help provide a vibrant environment of artists and makers who worked with residents to invent and build their own temporary facilities few of which would have survived a mission statement. [7] During 2003 it manifested as a protracted ‘exhibition’ 'Parasite Paradise' [8], created by local and international artists as playful alternatives to urban planning. They created a pub (there wasn’t one), a temporary theatre, an artificial ‘camping apartment’ complete with fake grass and recorded bird sounds, a temporary architectural office made out of old washing machines, a hotel in a carton. Nothing was built to last. All was process and experiment. By the end of Beyond they began to make sculptures, a series of old cars were cast in bronze, and notwithstanding setting fire to much of what remained, the town has ended up with a sculpture park.[9]

Grizedale Arts in the UK, (of the greasy pole festival mentioned above) acquired an old stone farmhouse on some green wooded lands in 1999 where ecologically aware thinkers and artists interact, and where much of the activity lately has been around growing food. Co-director Alistair Hudson raises the question of artists, folk artists and farmers, where does one begin and the other end? When a floating population of artists in residence and short term visitors interact with the people of the neighbouring village of Egremont on an annual festival there are unexpected results including taking several of the best performers in the village’s ongoing contest for the biggest liar which takes place in the local pub, down to London to perform at the Tate Britain, where they went down very well.

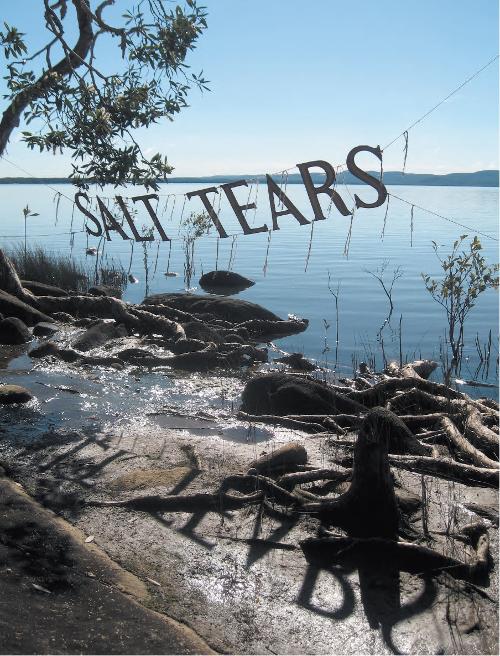

The philosophy of durational public art is attracting supporters around the globe. In Australia Simon Maidment has recently launched Satellite, an international network of thinkers, public art commissioners, and curators, who are dedicated to infiltrating cities and regions with new thinking about and practical manifestations of long term projects.[10] Maidment cites Claire Doherty as an inspiration. Founder of Situations [11] in Bristol, it was her project in New Zealand 'One Day Sculpture' [12] in collaboration with David Cross and Litmus Research Initiative at Massey University, comprising 20 different one-day events in various sites around New Zealand across 12 months in 2008-09, that introduced Australasia to high profile international practitioners such as Heather and Ivan Morison.

The Morisons are known for their 'Escape Vehicles', an embodiment of today’s popular culture preoccupation with the envisioning of apocalyptic scenarios. In the 'One Day Sculpture' project their event 'Journée des Barricades' involved blocking a major road in Wellington with a mountain of piled up hard rubbish including car bodies.

They are developing a new project titled 'Mr Clevver' for Tasmania in the summer of 2011 under the aegis of CAST. It will see an aged truck towing a ramshackle trailer from which will materialise performances by the Morisons in collaboration with a troupe of local puppeteers led by Andrew Harper and Pip Stafford. Starting from the moonscape of Queenstown, there will be no predetermined route and the minstrels will simply arrive in a small town one evening and announce a performance for the following day.[13]

The global ecological crisis gives credence to this kind of thinking not only in relation to remote and rural locations, with their often romantic overtones, but for cities. Respected Sydney architect and public sculptor Richard Goodwin said recently ‘transforming and rethinking built forms could bring a city to life and was possibly the greenest approach rather than using new materials.’[14]

One Japanese artist who did some rethinking of existing forms some years ago has ensured an entertaining international career building rooms around monumental statuary. Visitors to the Art Gallery of NSW noticed that the bronze equestrian figures flanking the entry were suddenly not there any more, until they climbed a ramp and entered the two rooms designed by Tatzu Nishi, a 70s living room which strangely had an oversized horse’s head emerging from a cabinet, and a chintzy bedroom with a large horse and rider trampling the bed.

A different kind of layered approach is exemplified by a new work of Chris Booth, still in progress at the time of writing, and funded by a private patron through a bequest. Very expensive and very large, comprising 200 tonnes of sandstone in a wave form, it overlooks Sydney Harbour in the Botanic Gardens. The artist identifies its evolution as geomorphology and in his addition of timber, mud and damp crevices he has also carefully provided habitat for micro bats, solitary bees, plants and other lifeforms whose habitat is threatened.

Melbourne has captured the public imagination as an early adopter of green planning and latterly for exercising the city’s intricate laneways. Many of the policies which have seen artists invited to play with the fabric of the city have been attributed to the influence of Rob Adams, senior planner at the City of Melbourne, who has championed the role of the arts in bringing out the depth and flavour of life in the multicultural metropolis. From this base has grown a public art program managed by Andrea Kleist which commissions individuals, groups and organisations with temporary works, festivals and Laneway commissions. A green refit on an old signal building on the Yarra just across from Southbank heralded the 2009 opening of Signal as a studio for 13 – 20 year olds who want to work with and learn from artists in various media.[15] Like Brisbane’s The Edge, a custom-built youth centre for new media next door to the State Library of Queensland, Signal’s program is strongly connected to current art practice with a constant flow of emerging and other artists. The high windows overlooking the river are a natural video screen for after dark public art and the inaugural piece '10 Transforming Youths', with its slowly morphing faces from spiky youth to droopy age by Philip Brophy set the pace for the building’s clientele.

The intersection of cities, politics and the projection of images, pioneered by Krystof Wodiczko, who made some works on an Australian visit in the 1980s, has been explored again recently by Deborah Kelly and other art activists in Sydney. With the technology of laser tagging opening up this field to gifted amateurs, cities around the world are becoming canvases for the temporary inscription of subversive words or images using a technique which projects virtual graffiti onto a building from a distance.[16] Young British artist/software inventor Theodore Watson who now works between the Netherlands and the US, has taken the idea further with augmented projections as well as full body interactive pieces.[17] In Tokyo a building has been designed by Tetradesign Architects in Tokyo with two large QR codes on its façade which passers-by can scan with their i-phones to reveal retailer updates and live tweets from shoppers. The urban experience will no doubt soon be awash with electronic signalling, offering opportunities beyond the retail.

The public purse whether accessed via state funding or indirectly through corporate profits needs to open up to models beyond a simple Percent for Art provision, or real estate- or freeway-enhancing monumental sculptural installations. Programs tackling art in the public arena like that at RMIT where students, graduates and staff work alongside each other to infiltrate real life situations are a rarity in Australia. University and research-based art practice, such as that of Situations in Bristol or the socially based SKOR in the Netherlands can lead the way in giving credence to activity which does not have a predetermined outcome but aims to subtly shift the focus from isolated spectacle to something which is considered in a more holistic way.

Footnotes

- ^ This was John Kaldor’s first Art Project. He has consistently sponsored innovative public art in Australia for three decades.

- ^ Other noteworthy public art festivals and events on the current calendar include the biennial SCAPE in Christchurch NZ, the Folkestone public art event in the UK and the Creative Time public art quadrennial on historic Governor’s Island between Manhatten and Brooklyn.

- ^ Locating the Producers - an on-going collaborative research initiative led by Paul O’Neill is a partnership between the public art research centre Situations at the University of the West of England (based at Spike Island in Bristol), ProjectBase in Cornwall and Dartington College of Arts/University College Falmouth.

- ^ For complete list of residents and projects seehttp://www.blauwehuis.org/blauwehuisv2/ (accessed 23 July 2010)

- ^ http://www.blauwehuis.org/blauwehuisv2/?news_id=1637

- ^ http://www.beyondutrecht.nl/index2.php?taal=en

- ^ http://www.changing-habitats.net/english/projects/leidsche_rijn.htm

- ^ http://www.skor.nl/artefact-1475-en.html

- ^ http://www.skor.nl/artefact-3876-en.html

- ^ http://www.satellite.org.au/about.php

- ^ http://www.situations.org.uk/index.html

- ^ www.onedaysculpture.org.nz The book of the event as well as being a discursive documentation of the project by multiple authors is an excellent guide to the terrain in general. Claire Doherty and David Cross (eds) One Day Sculpture, Kerber Verlag, Germany, 2009. ISBN 978-3-86678-333-1.

- ^ http://www.castgallery.org/current-program/projects

- ^ http://sydney-central.whereilive.com.au/news/story/sydney-wants-more-public-art/

- ^ http://www.melbourne.vic.gov.au/Signal/Pages/Signal.aspx

- ^ http://graffitiresearchlab.com/projects/laser-tag/

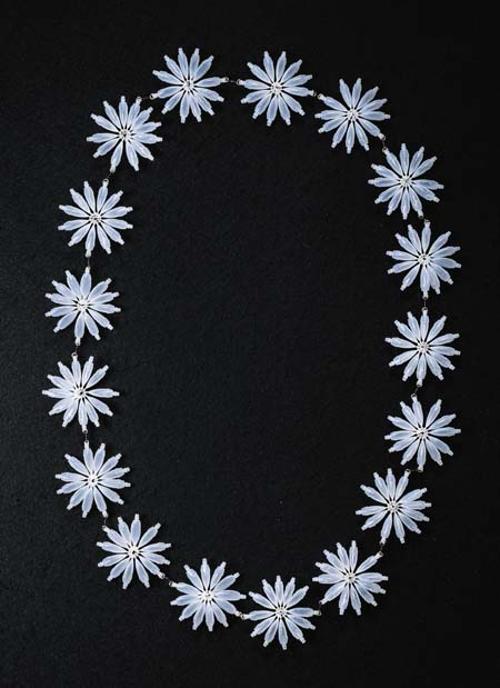

- ^ http://www.theowatson.com/ His interactive installation Funky Forest and Daisies was at Singapore Art Museum May 2010.