'Barks, birds and billabongs' was an international symposium rich with ideas and prospects. Its alliterative title, the romance of this famous last great salvage anthropology Expedition, the possibility of learning how it appeared from the other side, and thus the suggestion of more and more ideas and fragments of knowledge and images fitting together to form new and evolving patterns, all made it an intellectual adventure strongly influenced by the Dreaming as, in project director Margo Neale's words, a fluid and dynamic worldview. It was highly cross-disciplinary spanning sound, film, language, baskets, diet, paint, photographs, plants, fish, birds, stories, animals, insects, museums, libraries, anthropology and science, art and history. An actual member of the Expedition botanist Raymond Specht (who collected 13,500 plant specimens in 7 months using 10,160 kg of old newspaper he had brought along to dry them) was there and many relatives of the seventeen expeditioneers as well as Aboriginal people from the region, all of whose lives have been influenced by the Expedition. Geologist Gifford Miller, son of Expedition fishman Robert Rush Miller spoke of the intellectual thread of the expedition as still motivating scientific research today: 'What’s the footprint of humans? How do they fit into the landscape?’

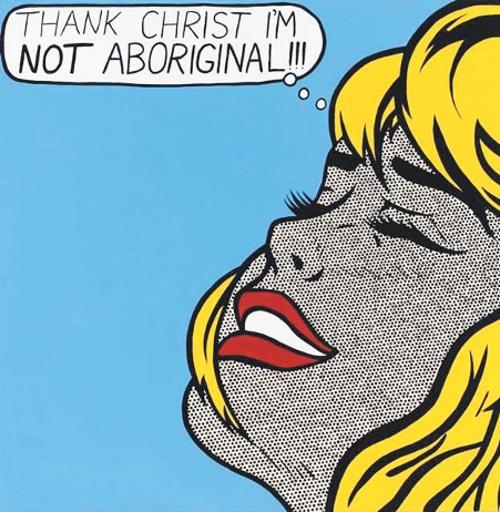

What was revealed and commented upon several times throughout the symposium is that nothing is free of values or politics, neither everyday life nor science nor history. What was collected, how it was collected, where it went, what it means - each of these are imbricated with stories of authority, trust, biases, accidents and personalities.

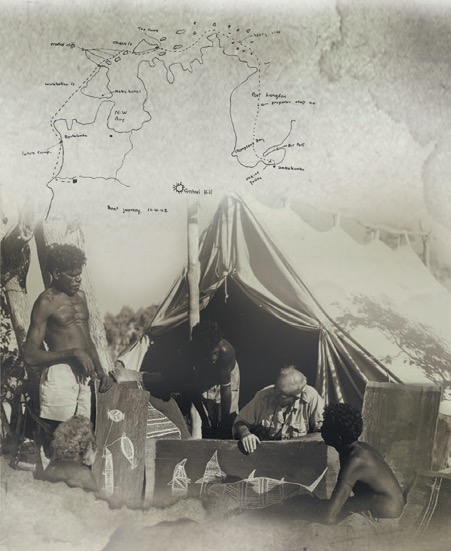

The Expedition is significant for people interested in Aboriginal art because it was the 500 ‘bark’ (some were on paper) paintings commissioned and collected by Charles Mountford during it that were distributed by the Australian government among Australian state galleries and museums in 1956 and that form the basis of their collections of Aboriginal art.

The Expedition came about through Charles Mountford giving a talk in Washington at the Smithsonian in 1946. They were so impressed with him that along with the National Geographic Society they offered to fund a joint American Australian Scientific Expedition with Mountford as its leader. Yet in Australia Mountford was considered an amateur opportunist by more academic anthropologists even though he contributed a great deal to the recognition of Aboriginal culture through his enthusiasm, publications and films. It was suggested at the symposium, perhaps apocryphally, that on his death his papers and other material were donated to the State Library of South Australia because the South Australian Museum would have thrown it all out.

A new book 'Collecting Cultures: Myth, Politics and Collaboration in the 1948 Arnhem Land Expedition' by Sally May was launched by National Museum of Australia Director Craddock Morton who in a short speech managed to mention Castro, Joseph Conrad, Gilligan’s Island and Patrick White before quoting William Faulkner – ‘The past is not dead. In fact it’s not even past’.

One of the best speakers was Ian McIntosh who spoke via satellite from America about the debates in Arnhem Land that were occurring about the time of the Expedition and revolved around big metaphysical questions such as ‘Was Christianity an expression of the Dreaming or did God give Yolgnu the Dreaming?’. McIntosh’s description of the way David Burrumurra, his chief Yolgnu informant, saw himself as an octopus as much as a man was incredibly vivid and somehow dovetailed into the scientific habit prevalent at the symposium of calling people fishmen or plantmen.

The revelations of old research were complemented by new research by Martin Thomas who in 2007 interviewed Gerry Blitner who assisted the expedition as a guide and translator and described Mountford as a tyrant who wanted everything his way, by Louis Hamby who has looked at every basket collected by the Expedition in every collection all over the world, by Josh Harris who described the quest for its films in the archives of the National Geographic Society as recently as 2007, and by radioman Tony MacGregor who discussed the recordings made by Colin Simpson the ABC journalist who joined the Expedition for 2 weeks and wrote the book 'Adam in Ochre' about his experiences.

Panels of indigenous people from the three sites in Arnhem Land where the Expedition had base camps Groote Eylandt, Yirrkala and Oenpelli (now Gunbalanya) added their voices to the symposium. The suggestion was made by Thomas Amagula for a museum on Groote Eylandt and empassioned requests were made for the return of the rest of the human remains removed during the Expedition. A satisfying outcome of the symposium is that the Smithsonian is now quietly discussing just this with the relevant Australian authorities.

A curious offbeat inclusion in the program was the short film made by linguist Bruce Birch who has been working on Croker Island for six years. The film was about stories concerning mammalman Dave Johnson fabled in Arnhemland to this day in oral history as the ‘American clever man’. He was an especially tall and fearless hunter of animals often going into the bush at night and returning with great hauls of bats and other nocturnal beasts. Through his taxidermy skills he was seen to bring animals back to life. In the stories he is said to have travelled a two week distance where there was no path overnight, to have taken a dead local man’s remains with him and then brought him back to life in America as a strong young man. Birch’s amateurish but absorbing film ended suddenly with some confronting footage of American archaeologist Frank Setzler waving bones in a cave like a madman in a voodoo movie.

The symposium was stringently and thoughtfully planned by Margo Neale, Sally May and Martin Thomas, with carefully researched papers that added to each other. The program was complemented by performances, both planned and impromptu, and the dinner where each table held large glass containers of fish and actor Jack Thompson, who was a jackeroo in the Territory in his youth, yarned with Bill Harney Junior who finished by playing the didgeridoo.

Sixty-one years after the Expedition the collections made on the trip are still not well-known and only small amounts are on display. So many stories begun in 1948 and added to in 2009 will be continued and most of the papers for the symposium went online as audio on demand on the 24th December which is pretty bloody impressive. At the end of the symposium along with congratulations warning words were heard from Ann McGrath, inaugural Director of the Australian Centre for Indigenous History at the ANU and co-author of the recently published 'How to Write History that People want to Read', about the deadening effects of too much protocol and the important role of love in research.